Editor’s note: This guest post was written by Andy Tomaswick, an electrical engineer who follows space science and technology.

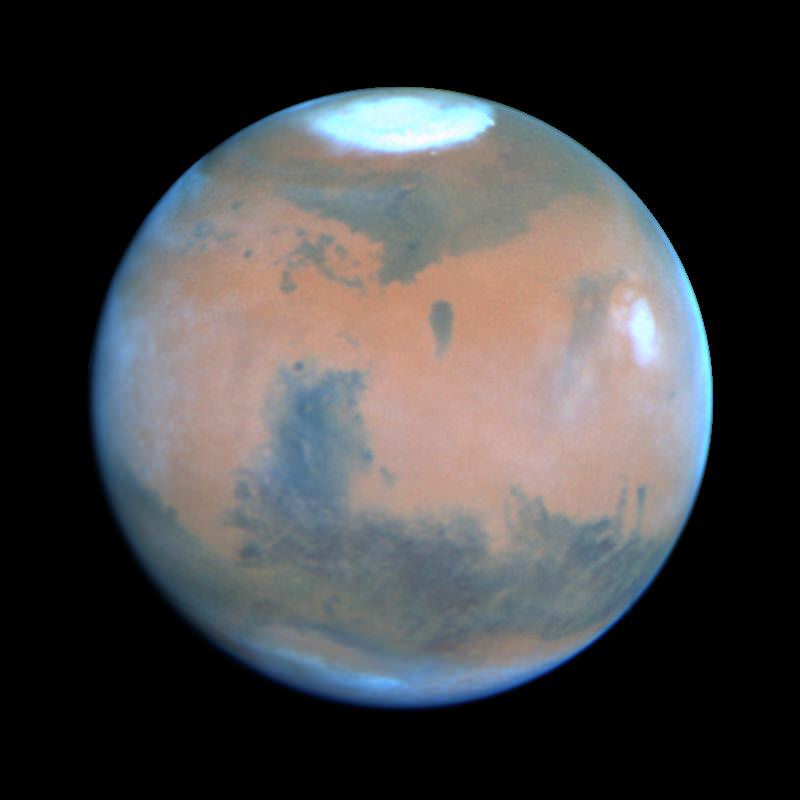

One of the most technically difficult tasks of any future manned missions to Mars is to get the astronauts safely on the ground. The combination of the high speed needed for a short trip in space and the much lighter Martian atmosphere creates an aerodynamics problem that has been solved only for robotic spacecraft so far. If people will one day walk Mars’ dusty surface, we will need to develop better Entry Descent and Landing (EDL) technologies first.

Those technologies are part of a recent meeting of the Lunar Planetary Institute (LPI), The Concepts and Approaches for Mars Exploration conference, held June 12-14 in Houston, which concentrated on the latest advances in technologies that might solve the EDL problem.

Of the multitude of technologies that were presented at the meeting, most seemed to involve a multi-tiered system comprising several different strategies. The different technologies that will fill those tiers are partly mission-dependent and all still need more testing. Three of the most widely discussed were Hypersonic Inflatable Aerodynamic Decelerators (HIADs), Supersonic Retro Propulsion (SRP), and various forms of aerobraking.

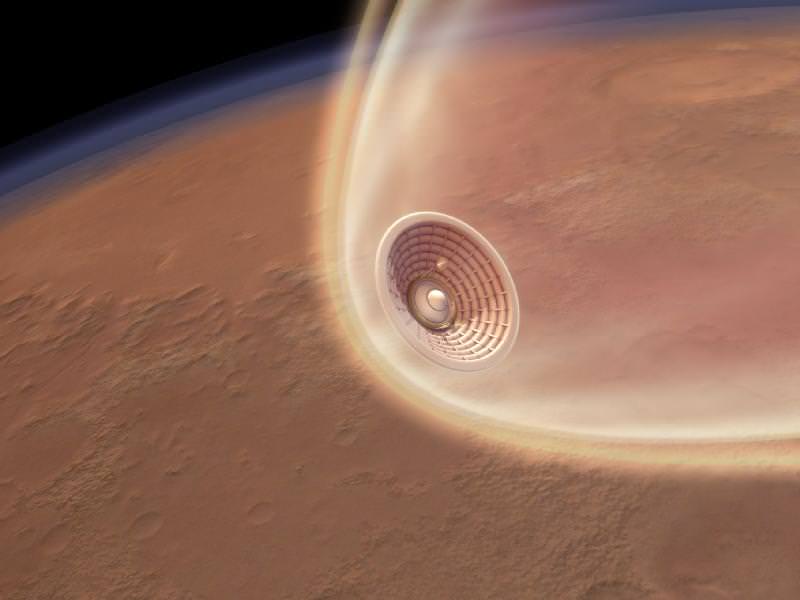

HIADs are essentially large heat shields, commonly found many types of manned reentry capsule used in the last 50 years of spaceflight. They work by using a large surface area to create enough drag through the atmosphere of a planet to slow the traveling craft to a reasonable speed. Since this strategy has worked so well on Earth for years, it is natural to translate the technology to Mars. There is a problem with the translation though.

HIADs rely on air resistance for its ability to decelerate the craft. Since Mars has a much thinner atmosphere than Earth, that resistance is not nearly as effective at slowing reentry. Because of this drop in effectiveness, HIADs are only considered for use with other technologies. Since it is also used as a heat shield, it must be attached to the ship at the beginning of reentry, when the air friction causes massive heating on some surfaces. Once the vehicle has slowed to a speed where heating is no longer an issue, the HIAD is released in order to allow other technologies to take over the rest of the braking process.

One of those other technologies is SRP. In many schemes, after the HIAD is released, SRP becomes primarily responsible for slowing the craft down. SRP is the type of landing technology commonly found in science fiction. The general idea is very simple. The same types of engines that accelerate the spacecraft to escape velocity on Earth can be turned around and used to stop that velocity upon reaching a destination. To slow the ship down, either flip the original rocket boosters around upon reentry or design forward-facing rockets that will only be used during landing. The chemical rocket technology needed for this strategy is already well understood, but rocket engines work differently when they are traveling at supersonic speeds. More testing must be done to design engines that can deal with the stresses of such velocities. SRPs also use fuel, which the craft will be required to carry the entire distance to Mars, making its journey more costly. The SRPs of most strategies are also jettisoned at some point during the descent. The weight shed and the difficulty of a controlled descent while following a pillar of flame to a landing site help lead to that decision.

Once the SRP boosters fall away, in most designs an aerobraking technology would take over. A commonly discussed technology at the conference was the ballute, a combination balloon and parachute. The idea behind this technology is to capture the air that is rushing past the landing craft and use it to fill a ballute that is tethered to the craft. The compression of the air rushing into the ballute would cause the gas to heat up, in effect creating a hot air balloon that would have similar lifting properties to those used on Earth. Assuming enough air is rushed into the ballute, it could provide the final deceleration needed to gently drop the landing craft off on the Martian surface, with minimal stress on the payload. However, the total amount this technology would slow the craft down is dependent on the amount of air it could inject into its structure. With more air come larger ballute, and more stresses on the material the ballute is made out of. With those considerations, it is not being considered as a stand-alone EDL technology.

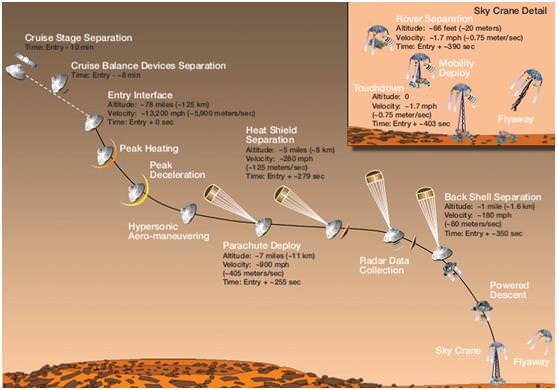

These strategies barely scratch the surface of proposed EDL methods that could be used by a human mission to Mars. Curiosity, the newest rover soon set to land on Mars, is using several, including a unique form of SRP known as the Sky Crane. The results of its systems will help scientists like those at the LPI conference determine what suite of EDL technologies will be the most effective for any future human missions to Mars.

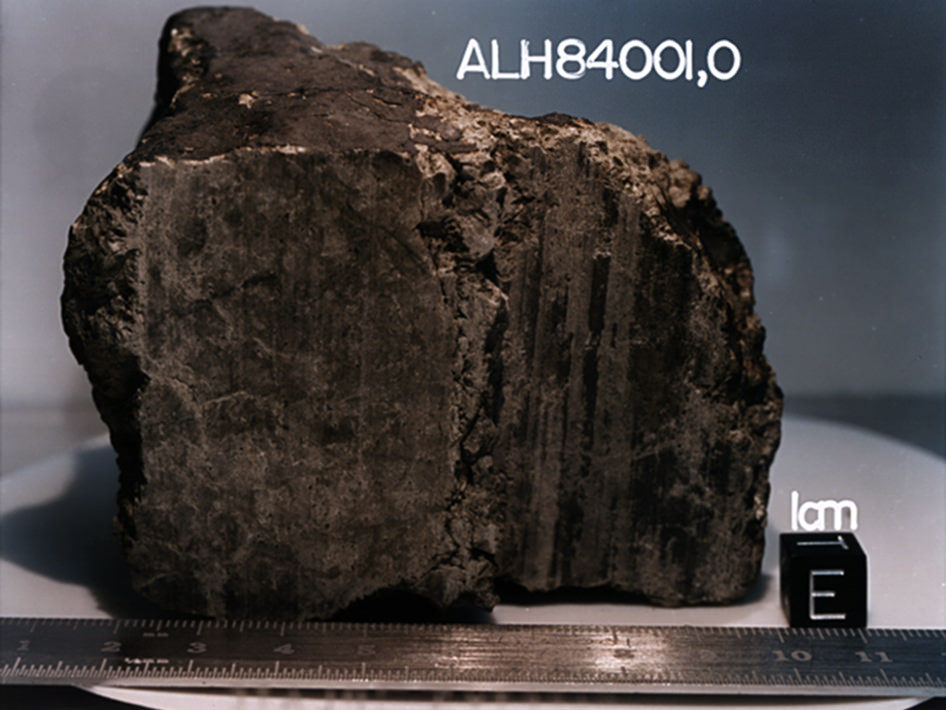

Lead image caption: Artist’s concept of Hypersonic Inflatable Aerodynamic Decelerator slowing the atmospheric entry of a spacecraft. Credit: NASA

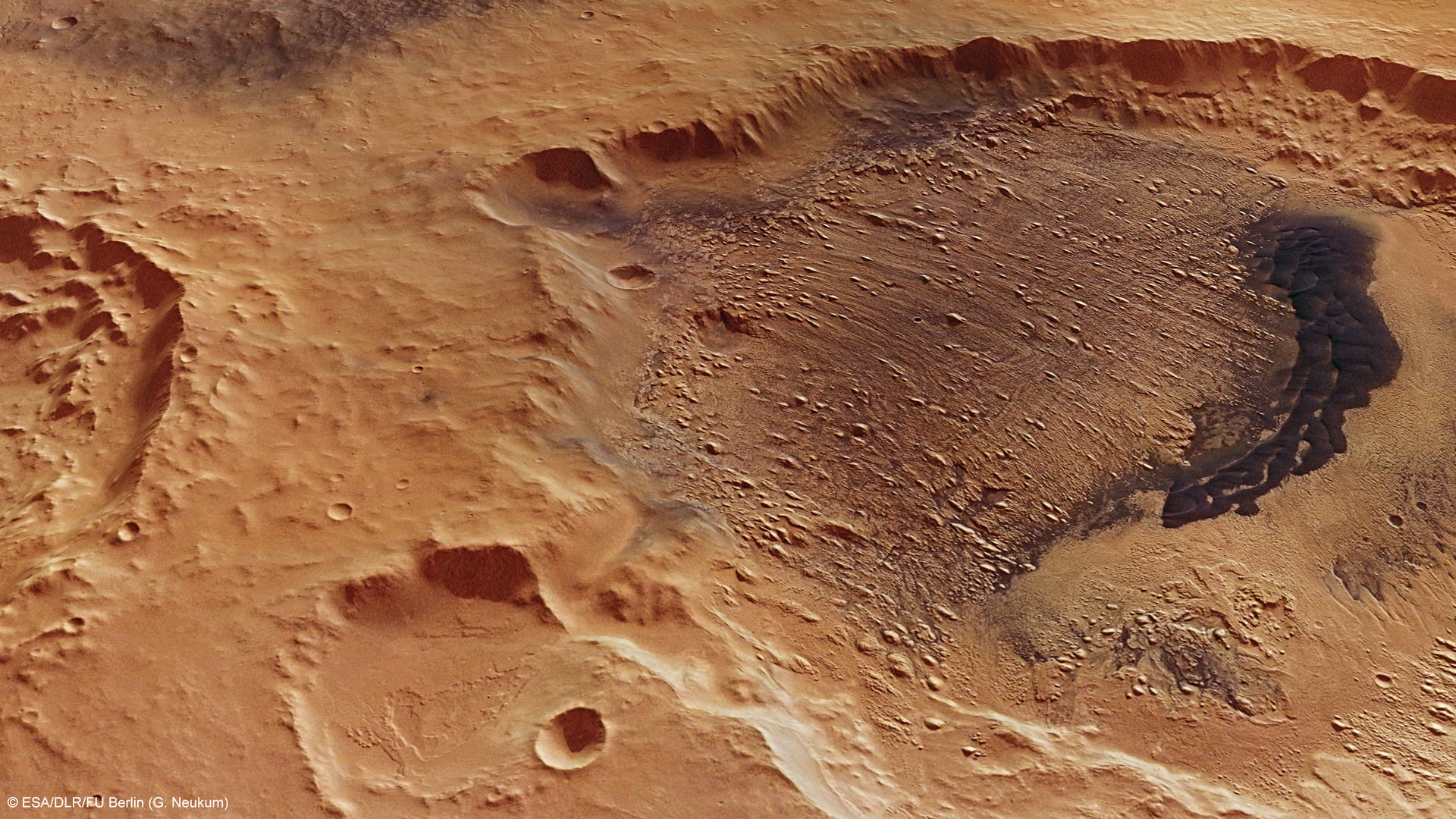

Second image caption: Supersonic jets are fired forward of a spacecraft in order to decelerate the vehicle during entry into the Martian atmosphere prior to parachute deployment. The image is of the Mars Science Lab at Mach 12 with 4 supersonic retropropulsion jets. Credit: NASA