On December 19th, 2013, the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Gaia spacecraft took to space with for a very ambitious mission. Over the course of its planned 5-year mission (which was recently extended), this space observatory would map over a billion stars, planets, comets, asteroids and quasars in order to create the largest and most precise 3D catalog of the Milky Way ever created.

Since that time, the ESA has made two data releases that cover the first three years of the Gaia mission. The second data release, which took on April 25th, 2018, has already proven to be a treasure trove for astronomers. In addition to the positions, distance indicators and motions of over a billion stars and celestial objects in the Milky Way Galaxy, it also contained a hidden gem – the proper motions of stars within the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC).

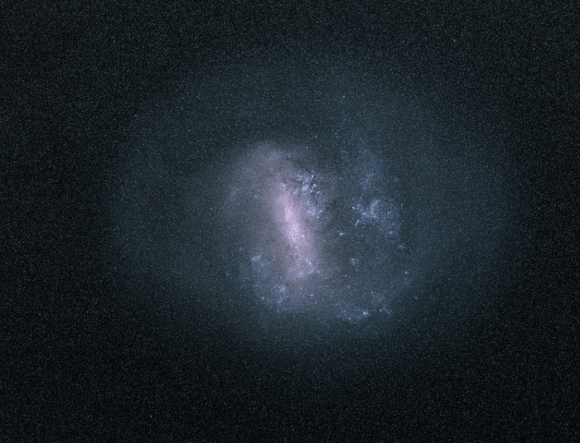

Located about 200,000 light-years from Earth, the LMC has dense clouds of dust that results in it experiencing high rates of star formation. In addition, it’s central bar is warped (where the east and west ends are nearer to the Milky Way), suggesting that it was once a barred dwarf spiral galaxy who’s spiral arms were disrupted by interaction with the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC) and the Milky Way.

For these reasons, astronomers have been hoping to derive the orbits of dwarf galaxies (and globular clusters) that revolve around the Milky Way. In so doing, they hope to learn more about how our galaxy evolved due to mergers with clusters and other galaxies. By determining the proper motions of the LMC’s stars, the Gaia mission has provided clues as to how the Milky Way and its largest satellite galaxy have interacted over time.

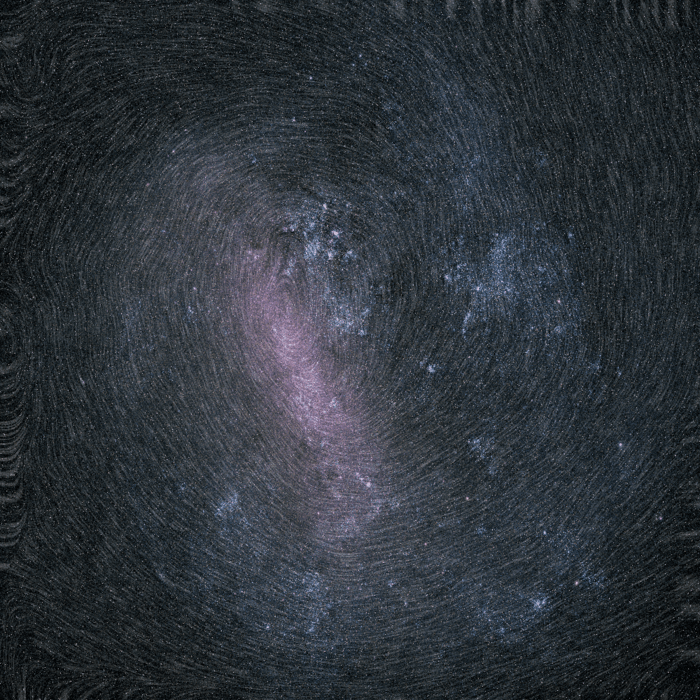

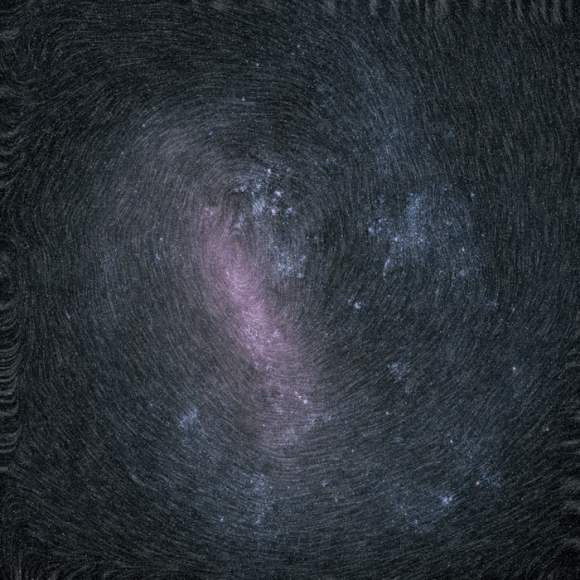

As you can see from the image (at top), the bar of the LMC is outlined in great detail, along with individual star-forming regions like the Tarantula Nebula (aka. 30 Doradus, which is visible just above the center of the galaxy). The image combines the total amount of radiation detected by the observatory in each pixel. The radiation measurements were then taken through different filters on the spacecraft to generate color information.

This allowed Gaia to obtain information about the total density of stars within the LMC as well as their proper motions. As you can see, the image is dominated by the brightest, most massive stars, which greatly outshine their fainter, lower-mass counterparts. The proper motions of the stars observed is represented as the texture of the image – which looks a lot like a fingerprint.

From this, scientists were able to see an imprint of the stars rotating clockwise around the center of the galaxy. Using this information, astronomers will be able to create new models on how the LMC, SMC, and Milky Way evolved together over time. This, in turn, could shed light on how galaxies like our own, formed and evolved over the course of billions of years.

As with other information contained in the first and second data releases, this latest discovery demonstrates that the Gaia mission is fulfilling its intended purpose. The third release of Gaia data is scheduled to take place in late 2020, with the final catalog being published in the 2020s. Meanwhile, an extension has already been approved for the Gaia mission, which will now remain in operation until the end of 2020 (to be confirmed at the end of this year).

And be sure to enjoy this animated view of the LMC’s rotation, courtesy of the ESA:

Further Reading: ESA