Universe Today has had the incredible opportunity of exploring various scientific fields, including impact craters, planetary surfaces, exoplanets, astrobiology, solar physics, comets, planetary atmospheres, planetary geophysics, cosmochemistry, meteorites, radio astronomy, extremophiles, organic chemistry, black holes, cryovolcanism, planetary protection, dark matter, supernovae, neutron stars, and exomoons, and how these separate but unique all form the basis for helping us better understand our place in the universe.

Continue reading “Evolutionary Biology: Why study it? What can it teach us about finding life beyond Earth?”Titan Probably Doesn’t Have the Amino Acids Needed for Life to Emerge

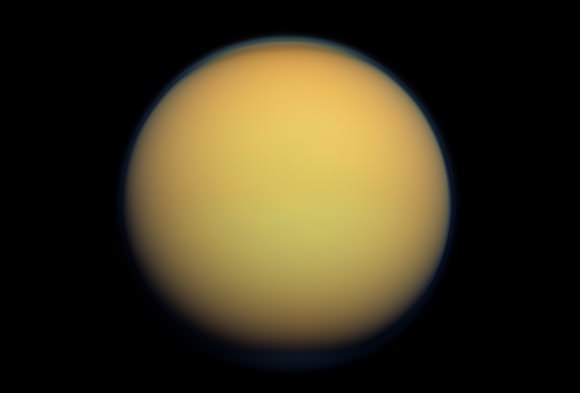

Does Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, possess the necessary ingredients for life to exist? This is what a recent study published in Astrobiology hopes to address as a team of international researchers led by Western University investigated if Titan, with its lakes of liquid methane and ethane, could possess the necessary organic materials, such as amino acids, that could be used to produce life on the small moon. This study holds the potential to help researchers and the public better understand the geochemical and biological processes necessary for life to emerge throughout the cosmos.

Continue reading “Titan Probably Doesn’t Have the Amino Acids Needed for Life to Emerge”Should We Send Humans to Titan?

Universe Today recently examined the potential for sending humans to Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, and the planet Venus, both despite their respective harsh surface environments. While human missions to these exceptional worlds could be possible in the future, what about farther out in the solar system to a world with much less harsh surface conditions, although still inhospitable for human life? Here, we will investigate whether Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, could be a feasible location for sending humans sometime in the future. Titan lacks the searing temperatures and crushing pressures of Venus along with the harsh radiation experienced on Europa. So, should we send humans to Titan?

Continue reading “Should We Send Humans to Titan?”Titan’s Atmosphere Recreated in an Earth Laboratory

Beyond Earth, the general scientific consensus is that the best place to search for evidence of extraterrestrial life is Mars. However, it is by no means the only place. Aside from the many extrasolar planets that have been designated as “potentially-habitable,” there are plenty of other candidates right here in our Solar System. These include the many icy satellites that are thought to have interior oceans that could harbor life.

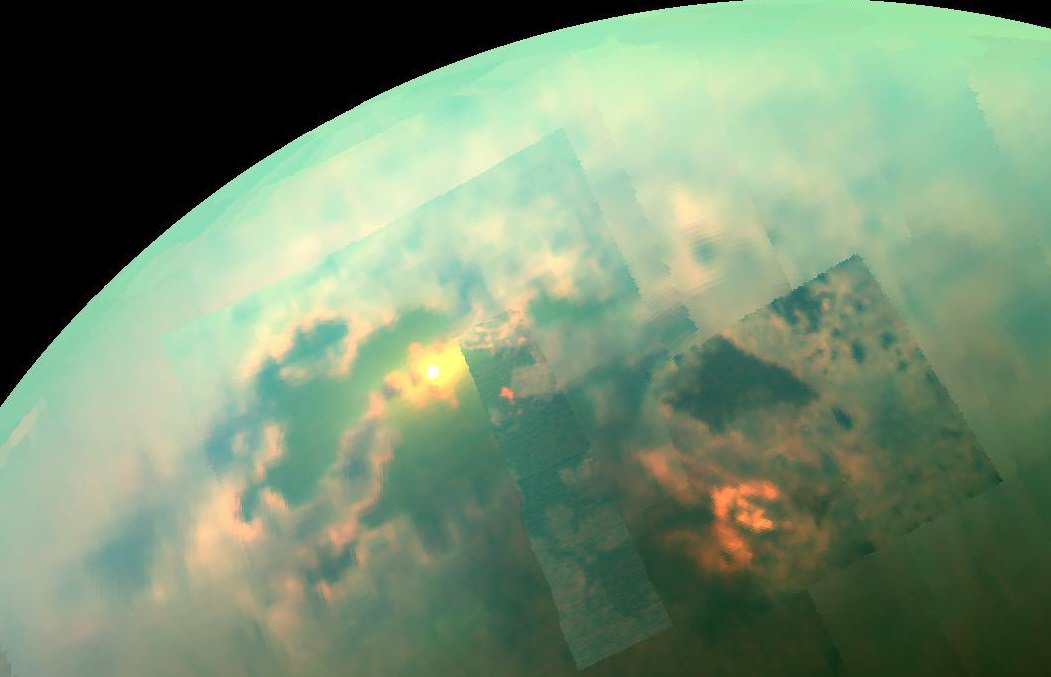

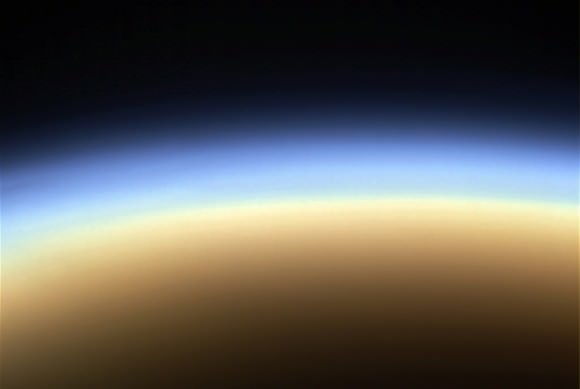

Among them is Titan, Saturn’s largest moon that has all kinds of organic chemistry taking place between its atmosphere and surface. For some time, scientists have suspected that the study of Titan’s atmosphere could yield vital clues to the early stages of the evolution of life on Earth. Thanks to new research led by tech-giant IBM, a team of researchers has managed to recreate atmospheric conditions on Titan in a laboratory.

Continue reading “Titan’s Atmosphere Recreated in an Earth Laboratory”Titan’s Atmosphere Has All the Ingredients For Life. But Not Life as We Know It

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), a team of scientists has identified a mysterious molecule in Titan’s atmosphere. It’s called cyclopropenylidene (C3H2), a simple carbon-based compound that has never been seen in an atmosphere before. According to the team’s study published in The Astronomical Journal, this molecule could be a precursor to more complex compounds that could indicate possible life on Titan.

Similarly, Dr. Catherine Neish of the University of Western Ontario’s Institute for Earth and Space Exploration (Western Space) and her colleagues in the European Space Agency (ESA) found that Titan has other chemicals that could be the ingredients for exotic life forms. In their study, which appeared in Astronomy & Astrophysics, they present Cassini mission data that revealed the composition of impact craters on Titan’s surface.

Continue reading “Titan’s Atmosphere Has All the Ingredients For Life. But Not Life as We Know It”NASA Detects More Chemicals on Titan that are Essential to Life

Saturn’s largest moon Titan may be the most fascinating piece of real-estate in the Solar System right now. Not surprising, given the fact that the moon’s dense atmosphere, rich organic environment and prebiotic chemistry are thought to be similar to Earth’s primordial atmosphere. As such, scientists believe that the moon could act as a sort of laboratory for studying the processes whereby chemical elements become the building blocks for life.

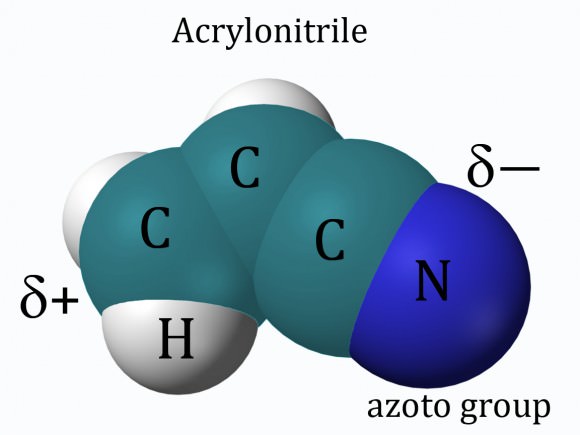

These studies have already led to a wealth of information, which included the recent discovery of “carbon chain anions” – which are thought to be building blocks for more complex molecules. And now, thanks to data from the the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, a team of NASA researchers have detected the presence of acrylonitrile, another chemical elements that could be the basis for life on that moon.

The study that details their findings – titled “ALMA detection and astrobiological potential of vinyl cyanide on Titan” – was published in the July 28th issue of the journal Science Advances. In it, the team explains how data from the ALMA array indicated that large quantities of acrylonitrile (C2H3CN) exist on Titan – most likely within the moon’s stratosphere.

As Maureen Palmer, a researcher with the Goddard Center for Astrobiology and the lead author on the paper, indicated in a NASA press release: “We found convincing evidence that acrylonitrile is present in Titan’s atmosphere, and we think a significant supply of this raw material reaches the surface.”

Also known as vinyl cyanide, acrylonitrile is used here on Earth in the manufacture of plastics. In the past, it has been speculated that this compound could be present in Titan’s atmosphere. However, it was only recently that scientists became aware of the possibility that it be the basis for living creatures within Titan’s rich organic environment – with its steady supply of carbon, hydrogen, and nitrogen.

This is based on a study that was conducted in 2015, where a team of Cornell scientists sought to determine if organic cells could form in Titan’s harsh environment. Given that the moon experiences average surface temperatures of -179 °C (-290 °F) and the atmosphere is predominantly nitrogen and hydrocarbons, lipid bilayer membranes (which are the foundation of life on Earth) could not survive there.

However, after conducting molecular simulations, the team determined that small organic nitrogen compounds would be capable of forming a sheet of material similar to a cell membrane. They also determined that these sheets could form hollow, microscopic spheres that they dubbed “azotosomes”, and that the best chemical candidate for this sheets would be acrylonitrile.

Such a material would be capable of surviving in liquid methane and at extremely cold temperatures, and would therefore be the most likely basis for organic life on Titan. As Michael Mumma, the director of the Goddard Center for Astrobiology, explained:

“The ability to form a stable membrane to separate the internal environment from the external one is important because it provides a means to contain chemicals long enough to allow them to interact. If membrane-like structures could be formed by vinyl cyanide, it would be an important step on the pathway to life on Saturn’s moon Titan.”

For the sake of their study, the Goddard team combined 11 high-resolution data sets from ALMA, which they retrieved from an archive of observations that were used to calibrate the array. From the data, Palmer and her team determined that acrylonitrile is relatively abundant in Titan’s atmosphere, reaching concentrations of up to 2.8 parts per billion. They also determined that it would be most common in Titan’s upper atmosphere.

It is here that carbon, hydrogen and nitrogen could chemically bond from exposure to sunlight and energetic particles from Saturn’s magnetic field. Eventually, the acrylonitrile would make its way down through the cold atmosphere and condense to form rain droplets that would fall to the surface. The team also estimated how much of this material would accumulate in Ligeia Mare – Titan’s second-largest methane lake – over time.

Finally, they calculated that within every cubic centimeter (cm³) of its volume, Ligeia Mare could form as many as 10,000,000 azotosomes. That roughly ten times the amount of bacteria that exists in the waters along Earth’s coastal regions. As Martin Cordiner, one of the senior authors on the paper, indicated, these findings are certainly encouraging when it comes to the search for extra-terrestrial life in our Solar System.

“The detection of this elusive, astrobiologically relevant chemical is exciting for scientists who are eager to determine if life could develop on icy worlds such as Titan,” he said. “This finding adds an important piece to our understanding of the chemical complexity of the solar system.”

Granted, the study and the basis for its conclusions are quite speculative. But they do show that within certain established parameters, life could exist within our Solar System well-beyond the limits of our Sun’s “habitable zone”. This study could also have implications in the hunt for life in extrasolar systems. If scientists can say definitively that life does not need warmer temperatures and liquid water to exist, it opens up immense possibilities.

In the coming decades, several missions are expected to go to Titan, ranging from submarines that will explore its methane lakes to drones and aerial platforms that will study its atmosphere and surface. Already, it is expected that they will obtain valuable information about the formation of the Saturn system. But to also discover entirely new forms of life? That would truly be Earth-shattering!

Further Reading: NASA, Science Advances

Exploring Titan with Aerial Platforms

Last week, from Monday Feb. 27th to Wednesday March 1st, NASA hosted the “Planetary Science Vision 2050 Workshop” at their headquarters in Washington, DC. During the course of the many presentations, speeches and addresses that made up the workshop, NASA and its affiliates shared their many proposals for the future of Solar System exploration.

A very popular theme during the workshop was the exploration of Titan. In addition to being the only other body in the Solar System with a nitrogen-rich atmosphere and visible liquid on its surface, it also has an environment rich in organic chemistry. For this reason, a team led by Michael Pauken (from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory) held a presentation detailing the many ways it can be explored using aerial vehicles.

The presentation, which was titled “Science at a Variety of Scientific Regions at Titan using Aerial Platforms“, was also chaired by members of the aerospace industry – such as AeroVironment and Global Aerospace from Monrovia, California, and Thin Red Line Aerospace from Chilliwack, BC. Together, they reviewed the various aerial platform concepts that have been proposed for Titan since 2004.

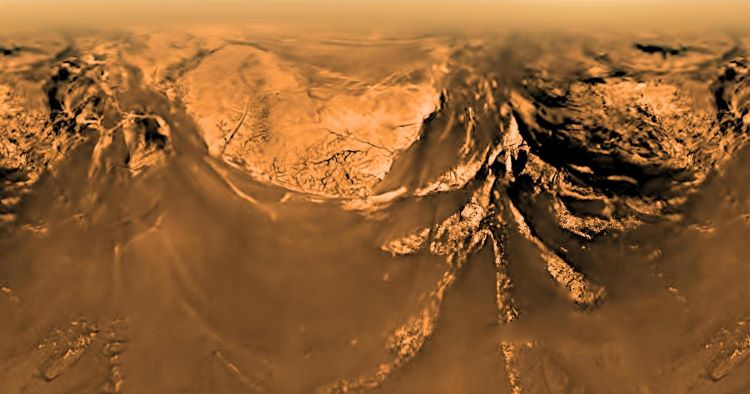

While the concept of exploring Titan with aerial drones and balloons dates back to the 1970s and 80s, 2004 was especially important since it was at this time that the Huygens lander conducted the first exploration of the moon’s surface. Since that time, many interesting and feasible proposals for aerial platforms have been made. As Dr. Pauken told Universe Today via email:

“The Cassini-Huygens mission revealed a lot about Titan we didn’t know before and that has also raised a lot more questions. It helped us determine that imaging the surface is possible below 40-km altitude so it’s exciting to know we could take aerial photos of Titan and send them back home.”

These concepts can be divided into two categories, which are Lighter-Than-Air (LTA) craft and Heavier-Than-Air (HTA) craft. And as Pauken explained, these are both well-suited when it comes to exploring a moon like Titan, which has an atmosphere that is actually denser than Earth’s – 146.7 kPa at the surface compared to 101 kPa at sea level on Earth – but only 0.14 times the gravity (similar to the Moon).

“The density of Titan’s atmosphere is higher than Earth’s so it is excellent for flying lighter-than-air vehicles like a balloon,” he said. “Titan’s low gravity is a benefit for heavier-than-air vehicles like helicopters or airplanes since they will ‘weigh’ less than they would on Earth.”

“The Lighter-than-air LTA concepts are buoyant and don’t need any energy to stay aloft, so more energy can be directed towards science instruments and communications. The Heavier-than-air concepts have to consume power to stay in the air which takes away from science and telecom. But HTA can be directed to targets more quickly and accurately the LTA vehicles which mostly drift with the winds.”

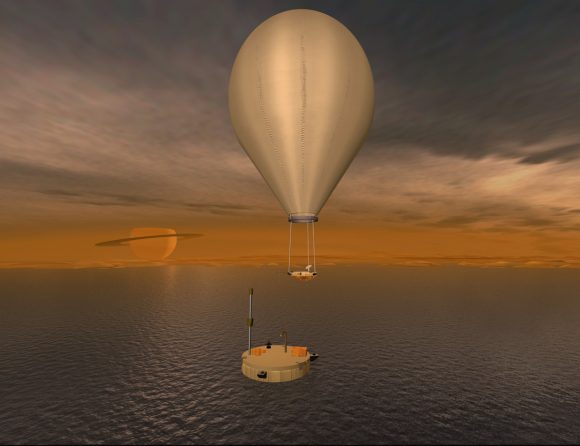

TSSM Montgolfiere Balloon:

Plans for using a Montgolfiere balloon to explore Titan go back to 2008, when NASA and the ESA jointly developed the Titan Saturn System Mission (TSSM) concept. A Flagship Mission concept, the TSSM would consist of three elements including a NASA orbiter and two ESA-designed in-situ elements – a lander to explore Titan’s lakes and a Montgolfiere balloon to explore its atmosphere.

The orbiter would rely on a Radioisotopic Power System (RPS) and Solar Electric Propulsion (SEP) to reach the Saturn system. And on its way to Titan, it would be responsible for examining Saturn’s magnetosphere, flying through the plumes of Enceladus to analyze it for biological markers, and taking images of Enceladus’ “Tiger Stripes” in the southern polar region.

Once the orbiter had achieved orbital insertion with Saturn, it would release the Montgolfiere during its first Titan flyby. Attitude control for the balloon would be provided by heating the ambient gas with RPS waste heat. The prime mission would last a total of about 4 years, comprised of a two-year Saturn tour, a 2-month Titan aero-sampling phase, and a 20-month Titan orbiting phase.

Of the benefits to this concept, the most obvious is the fact that a Montgolfiere vehicle powered by RPS could operate within Titan’s atmosphere for many years and would be able to change altitude with only minimal energy use. At the time, the TSSM concept was in competition with mission proposals for the moons of Europa and Ganymede.

In February of 2009, both the TSSM and the the Europa Jupiter System Mission (EJSM) concept were chosen to move forward with development, but the EJSM was given first priority. This mission was renamed the Europa Clipper, and is slated for launch in 2020 (and arriving at Europa by 2026).

Titan Helium Balloon:

Subsequent research on Montgolfiere balloons revealed that years of service and minimal energy expenditure could also be achieved in a much more compact balloon design. By combining an enveloped-design with helium, such a platform could operate in the skies of Titan for four times as long as balloons here on Earth, thanks to a much slower rate of diffusion.

Altitude control would also be possible with very modest amounts of energy, which could be provided either through pump or mechanical compression. Thus, with an RPS providing power, the platform could be expected to last longer that comparable balloon designs. This envelope-helium balloon could also be paired with a glider to create a lighter-than-air vehicle capable of lateral motion as well.

Examples of the this include the Titan Winged Aerobot (TWA, shown below), which was investigated as part of NASA’s Phase One 2016 Small-Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program. Developed by the Global Aerospace Corporation, in collaboration with Northrop Grumman, the TWA is a hybrid entry vehicle, balloon, and maneuverable glider with 3-D directional control that could satisfy many science objectives.

Like the Mongtolfiere concept, it would rely on minimal power provided by a single RPS. Its unique buoyancy system would also allow it to descend and ascend without the need for propulsion systems or control surfaces. One drawback is the fact that it cannot land on the moon’s surface to conduct research and then take off again. However, the design does allow for low-altitude flight, which would allow for the delivery of probes to the surface.

Other concepts that have been developed in recent years include heavier-than-air aircraft, which center around the development of fixed-wing vehicles and rotorcraft.

Fixed Wing Vehicles:

Concepts for fixed-wing aircraft have also been proposed in the past for a mission to Titan. A notable example of this is the Aerial Vehicle for In-situ and Airborne Titan Reconnaissance (AVIATR), an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) that was proposed by Jason Barnes and Lawrence Lemke in 2011 (of the University of Idaho and Central Michigan University, respectively).

Relying on an RPS that would use the waste heat of decaying Plutonium 238 to power a small rear-mounted turbine, this low-power craft would take advantage of Titan’s dense atmosphere and low gravity to conduct sustained flight. A novel “climb-then-glide” strategy, where the engine would shut down during glide periods, would also allow for power to be stored for optimal use during telecommunication sessions.

This addresses a major drawback of fixed-wing vehicles, which is the need to subdivide power between the needs of maintaining flight and conducting scientific research. However, the AVIATR is limited in one respect, in that it cannot descend to the surface to conduct science experiments or collect samples.

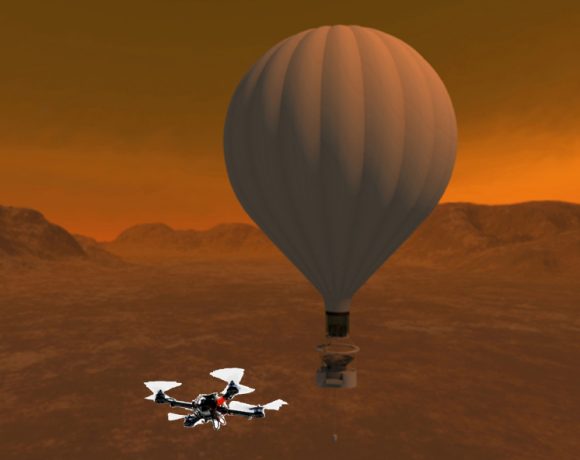

Rotorcraft:

Last, but not least, is the concept for a rotorcraft. In this case, the aerial platform would be a quadcopter, which would be well-suited to Titan’s atmosphere, would allow for easy ascent and descent, and for studies to be conducted on the surface. It would also take advantage of developments made in commercial UAVs and drones in recent years.

This mission concept would consist of two components. On the one hand, there’s the rotorcraft – known as a Titan Aerial Daughtercraft (TAD) – which would rely on a rechargeable battery system to power itself while conducting short-duration flights (about an hour at a time). The second component is the “Mothercraft”, which would take the form of a lander or balloon, which the TAD would return to between flights to recharge from an onboard RPS.

Currently, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory is developing a similar concept, known as the Mars Helicopter “Scout”, for use on Mars – which is expected to be launched aboard the Mars 2020 mission. In this case, the design calls for two coaxial counter-rotating rotors, which would provide the best thrust-to-weight ratio in Mars’ thin atmosphere.

Another rotorcraft concept is being pursued by Elizabeth Turtle and colleagues from John Hopkins APL and the University of Idaho (including James Barnes). With support from NASA and members of Goddard Space Flight Center, Pennsylvania State University, and Honeybee Robotics, they have proposed a concept known as the “Dragonfly“.

Their aerial vehicle would rely on four-rotors to take advantage of Titan’s thick atmosphere and low gravity. Its design would also allow it to easily obtain samples and determine the composition of the surface in multiple geological settings. These findings will be presented at the upcoming 48th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference – which will be taking place from March 20th to 24th in The Woodlands, Texas.

While the exploration of Titan is likely to take a back seat to the exploration of Europa in the coming decades, it is anticipated that a mission will be mounted before the mid-point of this century. Not only are the scientific goals very much the same in both cases – a chance to explore a unique environment and search for life beyond Earth – but the benefits will be comparable as well.

With every potentially life-bearing body we explore, we stand to learn more about how life began in our Solar System. And even if we do not find any life in the process, we stand to learn a great deal about the history and formation of the Solar System. On top of that, we will be one step closer to understanding humanity’s place in the Universe.

Further Reading: USRA

Life On Titan Possible Without Water

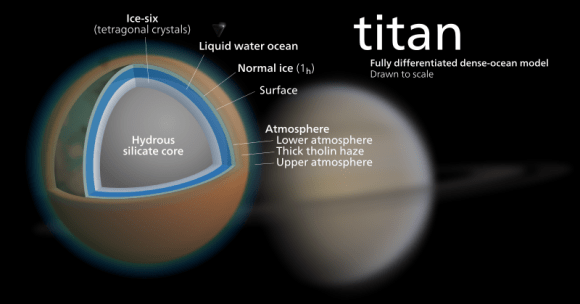

Saturn’s largest moon Titan is a truly fascinating place. Aside from Earth, it is the only place in the Solar System where rainfall occurs and there are active exchanges between liquids on the surface and fog in the atmosphere – albeit with methane instead of water. It’s atmospheric pressure is also comparable to Earth’s, and it is the only other body in the Solar System that has a dense atmosphere that is nitrogen-rich.

For some time, astronomers and planetary scientists have speculated that Titan might also have the prebiotic conditions necessary for life. Others, meanwhile, have argued that the absence of water on the surface rules out the possibility of life existing there. But according to a recent study produced by a research team from Cornell University, the conditions on Titan’s surface might support the formation of life without the need for water.

When it comes to searching for life beyond Earth, scientists focus on targets that possess the necessary ingredients for life as we know it – i.e. heat, a viable atmosphere, and water. This is essentially the “low-hanging fruit” approach, where we search for conditions resembling those here on Earth. Titan – which is very cold, quite distant from our Sun, and has a thick, hazy atmosphere – does not seem like a viable candidate, given these criteria.

However, according to the Cornell research team – which is led by Dr. Martin Rahm – Titan presents an opportunity to see how life could emerge under different conditions, one which are much colder than Earth and don’t involve water.

Their study – titled “Polymorphism and electronic structure of polyimine and its potential significance for prebiotic chemistry on Titan” – appeared recently in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). In it, Rahm and his colleagues examined the role that hydrogen cyanide, which is believed to be central to the origin of life question, may play in Titan’s atmosphere.

Previous experiments have shown that hydrogen cyanide (HCN) molecules can link together to form polyimine, a polymer that can serve as a precursor to amino acids and nucleic acids (the basis for protein cells and DNA). Previous surveys have also shown that hydrogen cyanide is the most abundant hydrogen-containing molecule in Titan’s atmosphere.

As Professor Lunine – the David C. Duncan Professor in the Physical Sciences and Director of the Cornell Center for Astrophysics and Planetary Science and co-author of the study – told Universe Today via email: “Organic molecules, liquid lakes and seas (but of methane, not water) and some amount of solar energy reaches the surface. So this suggests the possibility of an environment that might host an exotic form of life.”

Using quantum mechanical calculations, the Cornell team showed that polyimine has electronic and structural properties that could facilitate prebiotic chemistry under very cold conditions. These involve the ability to absorb a wide spectrum of light, which is predicted to occur in a window of relative transparency in Titan’s atmosphere.

Another is the fact that polyimine has a flexible backbone, and can therefore take on many different structures (aka. polymorphs). These range from flat sheets to complex coiled structures, which are relatively close in energy. Some of these structures, according to the team, could work to accelerate prebiotic chemical reactions, or even form structures that could act as hosts for them.

“Polyimine can form sheets,” said Lunine, “which like clays might serve as a catalytic surface for prebiotic reactions. We also find the polyimine absorbs sunlight where Titan’s atmosphere is quite transparent, which might help to energize reactions.”

In short, the presence of polyimine could mean that Titan’s surface gets the energy its needs to drive photochemical reactions necessary for the creation of organic life, and that it could even assist in the development of that life. But of course, no evidence has been found that polyimine has been produced on the surface of Titan, which means that these research findings are still academic at this point.

However, Lunine and his team indicate that hydrogen cyanide may very well have lead to the creation of polyimine on Titan, and that it might have simply escaped detection because of Titan’s murky atmosphere. They also added that future missions to Titan might be able to look for signs of the polymer, as part of ongoing research into the possibility of exotic life emerging in other parts of the Solar System.

“We would need an advanced payload on the surface to sample and search for polyimines,” answered Lunine, “or possibly by a next generation spectrometer from orbit. Both of these are “beyond Cassini”, that is, the next generation of missions.”

Perhaps when Juno is finished surveying Jupiter’s atmosphere in two years time, NASA might consider retasking it for a flyby of Titan? After all, Juno was specifically designed to peer beneath a veil of thick clouds. They don’t come much thicker than on Titan!

Further Reading: PNAS