Just like Isaac Newton, Galileo and Albert Einstein, I’m not sure exactly when I became aware of Peter Higgs. He has been one of those names that anyone who has even the slightest interest in science, especially physics, has become aware of at some point. Professor Higgs was catapulted to fame by the concept of the Higgs Boson – or God Particle as it became known. Sadly, this shy yet key player in the world of physics passed away earlier this month.

Continue reading “Peter Higgs Dies at 94”CERN Wants to Build an Enormous New Atom Smasher: the Future Circular Collider

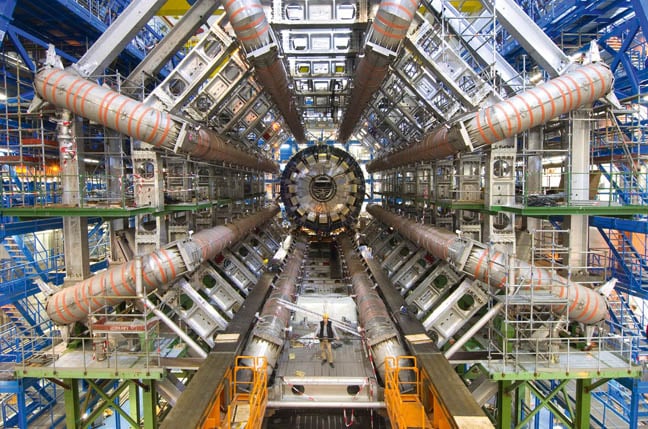

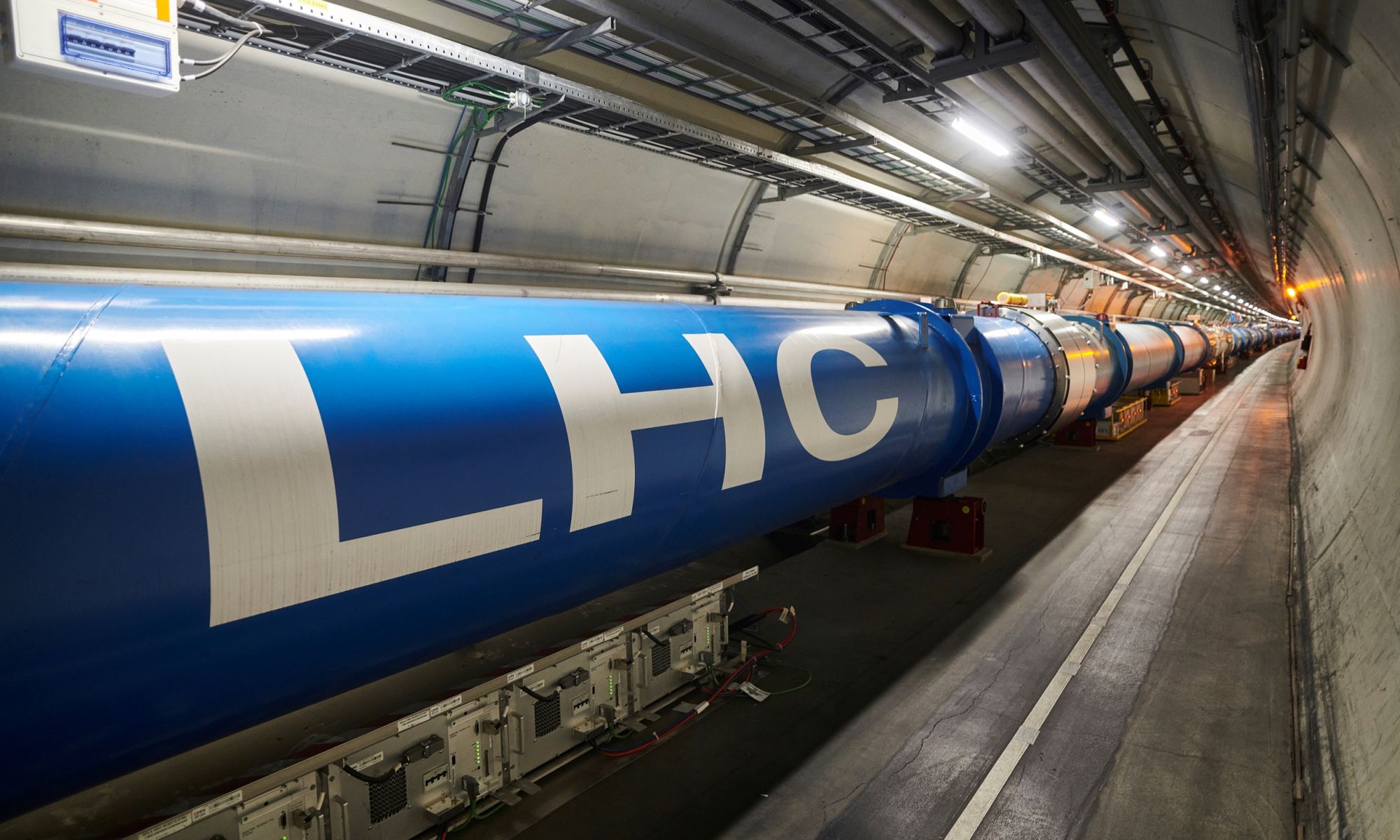

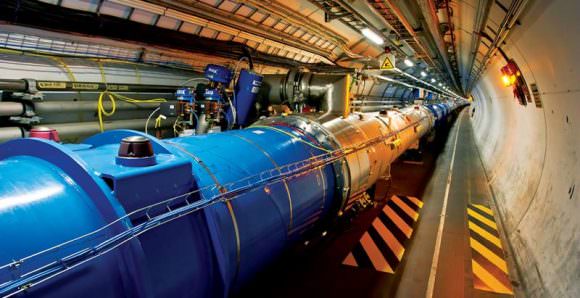

One of my favourite science and engineering facts is that an underground river was frozen to enable the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) to be built! On its completion, it helped to complete the proverbial jigsaw of the Standard Model with is last piece, the Higgs Boson. But that’s about as far as it has got with no other exciting leaps forward in uniting gravity and quantum physics. Plans are now afoot to build a new collider that will be three times longer than the LHC and it will be capable of smashing particles together with significantly more energy.

Continue reading “CERN Wants to Build an Enormous New Atom Smasher: the Future Circular Collider”LHC Scientists Find Three Exotic Particles — and Start Hunting for More

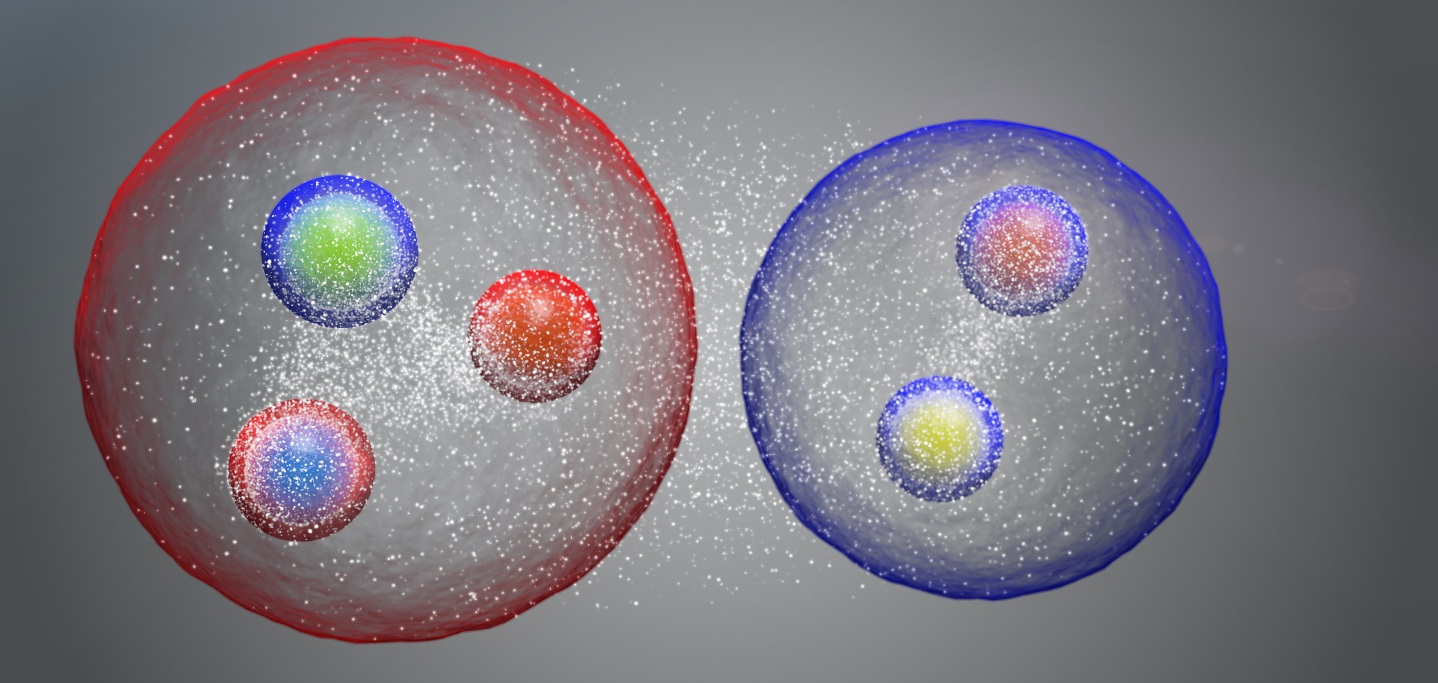

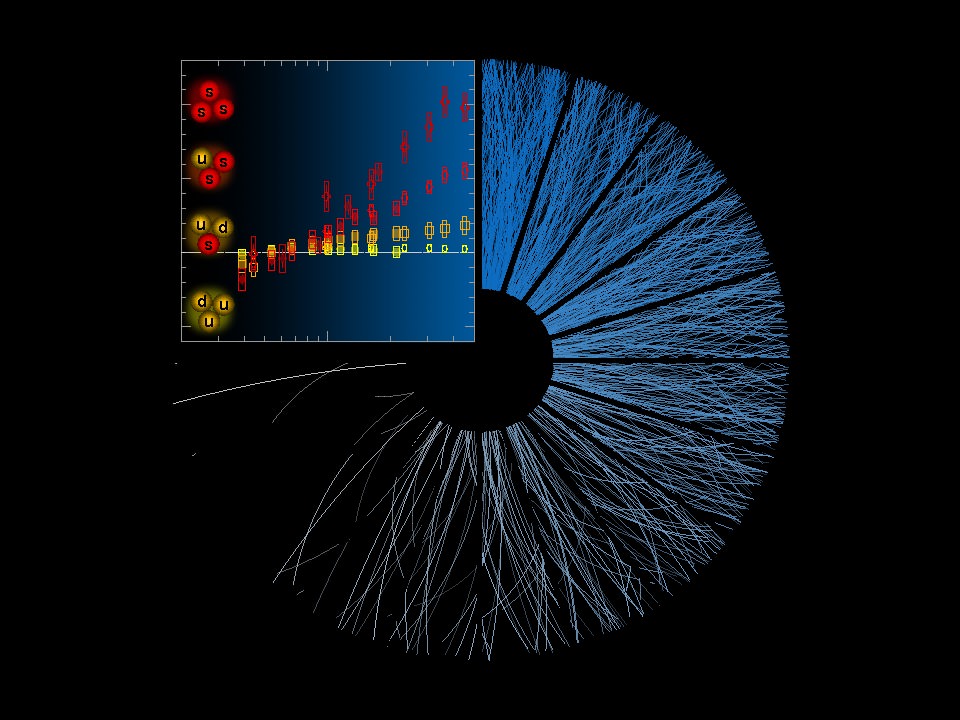

Physicists say they’ve found evidence in data from Europe’s Large Hadron Collider for three never-before-seen combinations of quarks, just as the world’s largest particle-smasher is beginning a new round of high-energy experiments.

The three exotic types of particles — which include two four-quark combinations, known as tetraquarks, plus a five-quark unit called a pentaquark — are totally consistent with the Standard Model, the decades-old theory that describes the structure of atoms.

In contrast, scientists hope that the LHC’s current run will turn up evidence of physics that goes beyond the Standard Model to explain the nature of mysterious phenomena such as dark matter. Such evidence could point to new arrays of subatomic particles, or even extra dimensions in our universe.

Continue reading “LHC Scientists Find Three Exotic Particles — and Start Hunting for More”Large Hadron Collider Restarts, Shooting Protons at Record Energy Levels

Europe’s Large Hadron Collider has started up its proton beams again at unprecedented energy levels after going through a three-year shutdown for maintenance and upgrades.

It only took a couple of days of tweaking for the pilot streams of protons to reach a record energy level of 6.8 tera electronvolts, or TeV. That exceeds the previous record of 6.5 TeV, which was set by the LHC in 2015 at the start of the particle collider’s second run.

The new level comes “very close to the design energy of the LHC, which is 7 TeV,” Jörg Wenninger, head of the LHC beam operation section and LHC machine coordinator at CERN, said today in a video announcing the milestone.

When the collider at the French-Swiss border resumes honest-to-goodness science operations, probably within a few months, the international LHC team plans to address mysteries that could send theories of physics in new directions.

Continue reading “Large Hadron Collider Restarts, Shooting Protons at Record Energy Levels”

The Large Hadron Collider has been Shut Down, and Will Stay Down for Two Years While they Perform Major Upgrades

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is getting a big boost to its performance. Unfortunately, for fans of ground-breaking physics, the whole thing has to be shut down for two years while the work is done. But once it’s back up and running, its enhanced capabilities will make it even more powerful.

Continue reading “The Large Hadron Collider has been Shut Down, and Will Stay Down for Two Years While they Perform Major Upgrades”

Another Strange Discovery From LHC That Nobody Understands

There are some strange results being announced in the physics world lately. A fluid with a negative effective mass, and the discovery of five new particles, are all challenging our understanding of the universe.

New results from ALICE (A Large Ion Collider Experiment) are adding to the strangeness.

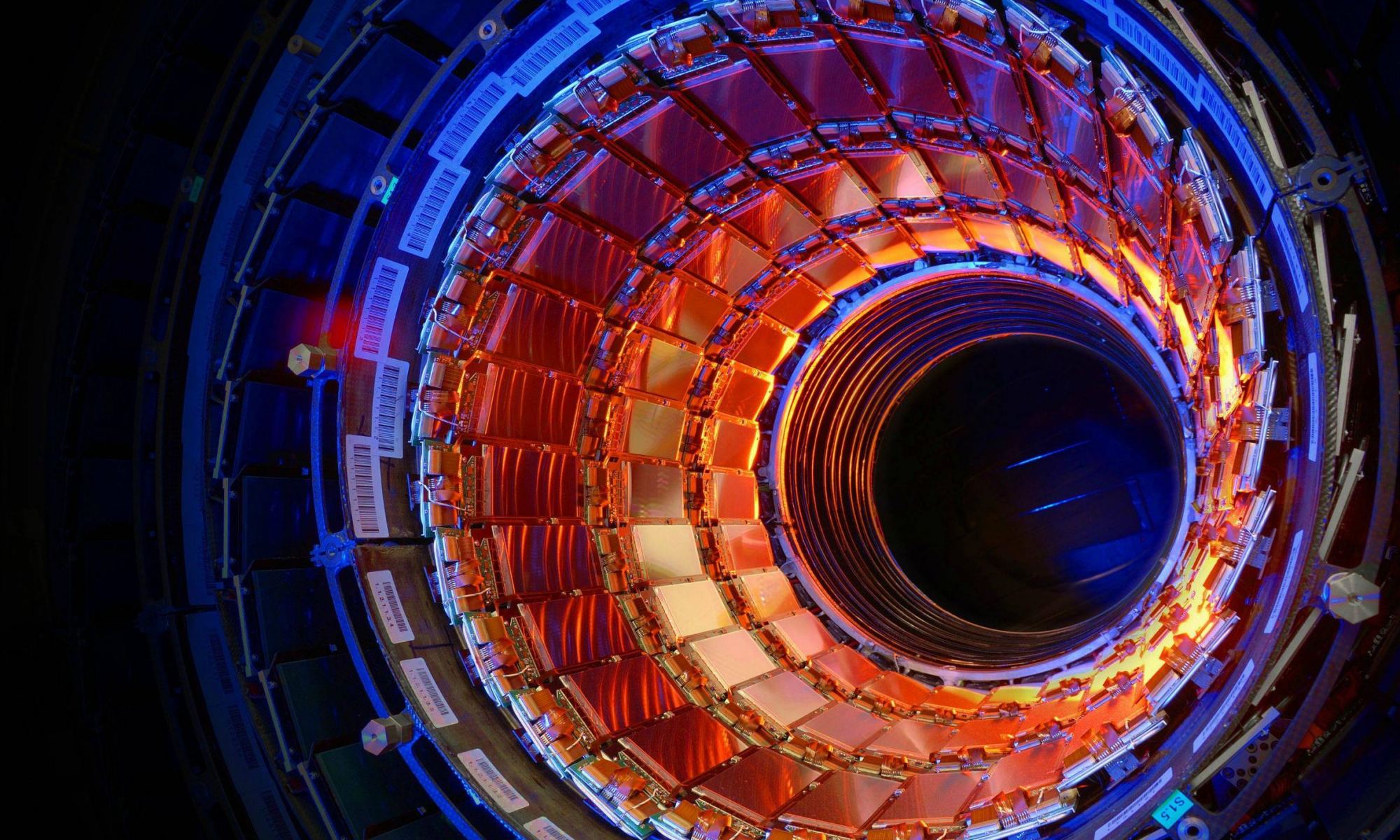

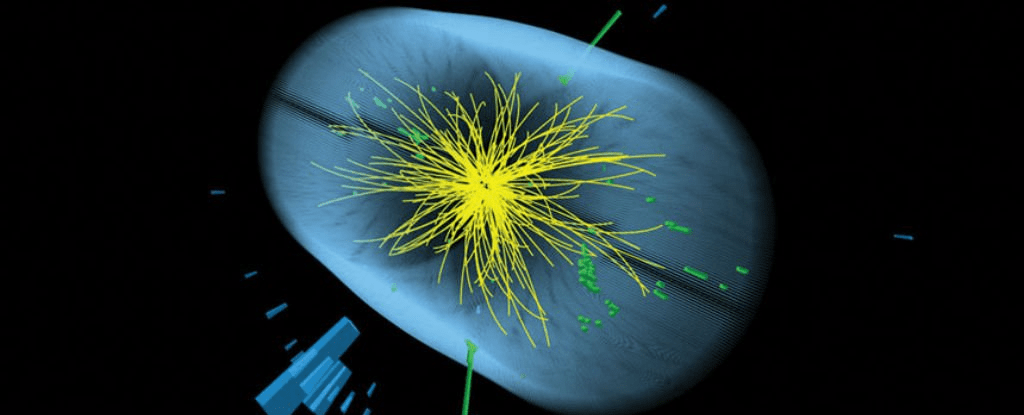

ALICE is a detector on the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). It’s one of seven detectors, and ALICE’s role is to “study the physics of strongly interacting matter at extreme energy densities, where a phase of matter called quark-gluon plasma forms,” according to the CERN website. Quark-gluon plasma is a state of matter that existed only a few millionths of a second after the Big Bang.

In what we might call normal matter—that is the familiar atoms that we all learn about in high school—protons and neutrons are made up of quarks. Those quarks are held together by other particles called gluons. (“Glue-ons,” get it?) In a state known as confinement, these quarks and gluons are permanently bound together. In fact, quarks have never been observed in isolation.

The LHC is used to collide particles together at extremely high speeds, creating temperatures that can be 100,000 times hotter than the center of our Sun. In new results just released from CERN, lead ions were collided, and the resulting extreme conditions come close to replicating the state of the Universe those few millionths of a second after the Big Bang.

In those extreme temperatures, the state of confinement was broken, and the quarks and gluons were released, and formed quark-gluon plasma.

So far, this is pretty well understood. But in these new results, something additional happened. There was increased production of what are called “strange hadrons.” Strange hadrons themselves are well-known particles. They have names like Kaon, Lambda, Xi and Omega. They’re called strange hadrons because they each have one “strange quark.”

If all of this seems a little murky, here’s the dinger: Strange hadrons may be well-known particles, because they’ve been observed in collisions between heavy nuclei. But they haven’t been observed in collisions between protons.

“Being able to isolate the quark-gluon-plasma-like phenomena in a smaller and simpler system…opens up an entirely new dimension for the study of the properties of the fundamental state that our universe emerged from.” – Federico Antinori, Spokesperson of the ALICE collaboration.

“We are very excited about this discovery,” said Federico Antinori, Spokesperson of the ALICE collaboration. “We are again learning a lot about this primordial state of matter. Being able to isolate the quark-gluon-plasma-like phenomena in a smaller and simpler system, such as the collision between two protons, opens up an entirely new dimension for the study of the properties of the fundamental state that our universe emerged from.”

Enhanced Strangeness?

The creation of quark-gluon plasma at CERN provides physicists an opportunity to study the strong interaction. The strong interaction is also known as the strong force, one of the four fundamental forces in the Universe, and the one that binds quarks into protons and neutrons. It’s also an opportunity to study something else: the increased production of strange hadrons.

In a delicious turn of phrase, CERN calls this phenomenon “enhanced strangeness production.” (Somebody at CERN has a flair for language.)

Enhanced strangeness production from quark-gluon plasma was predicted in the 1980s, and was observed in the 1990s at CERN’s Super Proton Synchrotron. The ALICE experiment at the LHC is giving physicists their best opportunity yet to study how proton-proton collisions can have enhanced strangeness production in the same way that heavy ion collisions can.

According to the press release announcing these results, “Studying these processes more precisely will be key to better understand the microscopic mechanisms of the quark-gluon plasma and the collective behaviour of particles in small systems.”

I couldn’t have said it better myself.

Is A New Particle About To Be Announced?

Particle physicists are an inquisitive bunch. Their goal is a working, complete model of the particles and forces that make up the Universe, and they pursue that goal with a vigour matched by few other professions.

The Standard Model of Physics is the result of their efforts, and for 25 years or so, it has guided our thinking and understanding of particle physics. The best tool we have for studying physics further is the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), near Geneva, Switzerland. And some recent, intriguing results from the LHC points to the existence of a newly discovered particle.

The LHC has four separate detectors. Two of them are “general purpose” detectors, called ATLAS and CMS. Last year, separate experiments in both the ATLAS and CMS detectors produced what is best called a “bump” in their data. Initially, the two teams conducting the experiments were puzzled by the data. But when they compared them, they found that the bumps in their data were the same in both experiments, and they hinted at what could be a new type of particle, never before detected.

The two experiments involved smashing protons into each other at near-relativistic speeds. The collisions produced more high-energy photons than theory predicts. Not a lot more, but physics is a detailed endeavour, so even a slight increase in the amount of photons produced is a big deal. In physics, everything happens for a reason.

To be more specific, ATLAS and CMS recorded increased activity at an energy level around 750 giga electron-volts (GeV). What that means, for all you non-particle physicists, is that the new particle decays into two photons at the point of the proton-proton collision. If the new particle exists, that is.

A new particle would be a huge discovery. The Standard Model has describe all the particles present in nature pretty well. It even predicted the existence of one type of particle, the Higgs Boson, long before the LHC actually verified its existence. The discovery of a new type of particle would be very exciting news indeed, and could break the Standard Model.

Since this data from the experiments at the LHC was released last year, the physics world has been buzzing. Over 100 papers have been written to try to explain what the results might mean. But some caution is required.

The first thing scientists do when faced with results like this is to try to quantify the likelihood that it could be chance. If only one experiment had this bump in its data, then the likelihood that it was just a chance occurrence is pretty high. There are many reasons why an experiment can have a result like this, which is why repeatability is such a big deal in science. But when two independent, separate, experiments have the same result, people’s ears perk up.

A few months have passed since the experiments were run, and in that time, the experimenters have tried to determine exactly what the likelihood is of these result occurring by chance. After working with the data, a funny thing has happened. The significance of the extra photons detected by CMS has risen, while the significance of the extra photons detected by ATLAS has fallen. This has definitely left physicists scratching their heads.

Also in that time, about four main explanations for the experimental results have percolated to the surface. One states that the new particle, if it exists, is made up of smaller particles, similar to how a proton is made up of quarks. These smaller particles could be held together by an unknown force. Some theoretical physicists think this is the best fit with the data.

Another possibility is that the new particle is a heavier version of the Higgs Boson. About 12 times heavier. Or it could be that the Higgs Boson itself is made up of smaller particles, and that’s what the experiment detected.

![The Standard Model of Elementary Particles. Image: By MissMJ - Own work by uploader, PBS NOVA [1], Fermilab, Office of Science, United States Department of Energy, Particle Data Group, CC BY 3.0](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Standard_Model_of_Elementary_Particles.svg_-580x436.png)

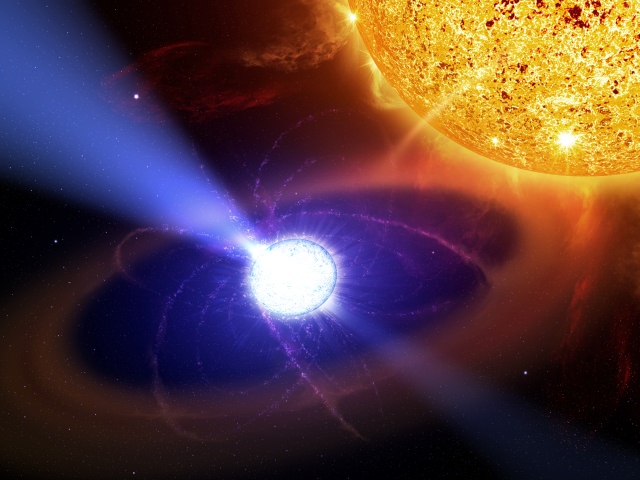

Or, it could be the much-hypothesized graviton, the theoretical particle that carries the gravitational force. The four fundamental forces in the Universe are electromagnetism, the strong nuclear force, the weak nuclear force, and gravity. So far, we have discovered the particles that transmit all of those forces, except for gravity. If their was a new particle detected, and if it proved to be the graviton, that would be enormous, earth-shattering news. At least for those who are passionate about understanding nature.

That’s a lot of “ifs” though.

There are a lot of holes in our knowledge of the Universe, and physicists are eager to fill those gaps. The discovery of a new particle might very well answer some basic questions about dark matter, dark energy, or even gravity itself. But there’s a lot more experimentation to be done before the existence of a new particle can be announced.

Who Discovered Helium?

Scientists have understood for some time that the most abundant elements in the Universe are simple gases like hydrogen and helium. These make up the vast majority of its observable mass, dwarfing all the heavier elements combined (and by a wide margin). And between the two, helium is the second lightest and second most abundant element, being present in about 24% of observable Universe’s elemental mass.

Whereas we tend to think of Helium as the hilarious gas that does strange things to your voice and allows balloons to float, it is actually a crucial part of our existence. In addition to being a key component of stars, helium is also a major constituent in gas giants. This is due in part to its very high nuclear binding energy, plus the fact that is produced by both nuclear fusion and radioactive decay. And yet, scientists have only been aware of its existence since the late 19th century.