KENNEDY SPACE CENTER VISITOR COMPLEX, FL – America’s pioneering astronauts who braved the perils of the unknown and put their lives on the line at the dawn of the space age atop mighty rockets that propelled our hopes and dreams into the new frontier of outer space and culminated with NASA’s Apollo lunar landings, are being honored with the eye popping new ‘Heroes and Legends’ attraction at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex (KSCVC) in Florida.

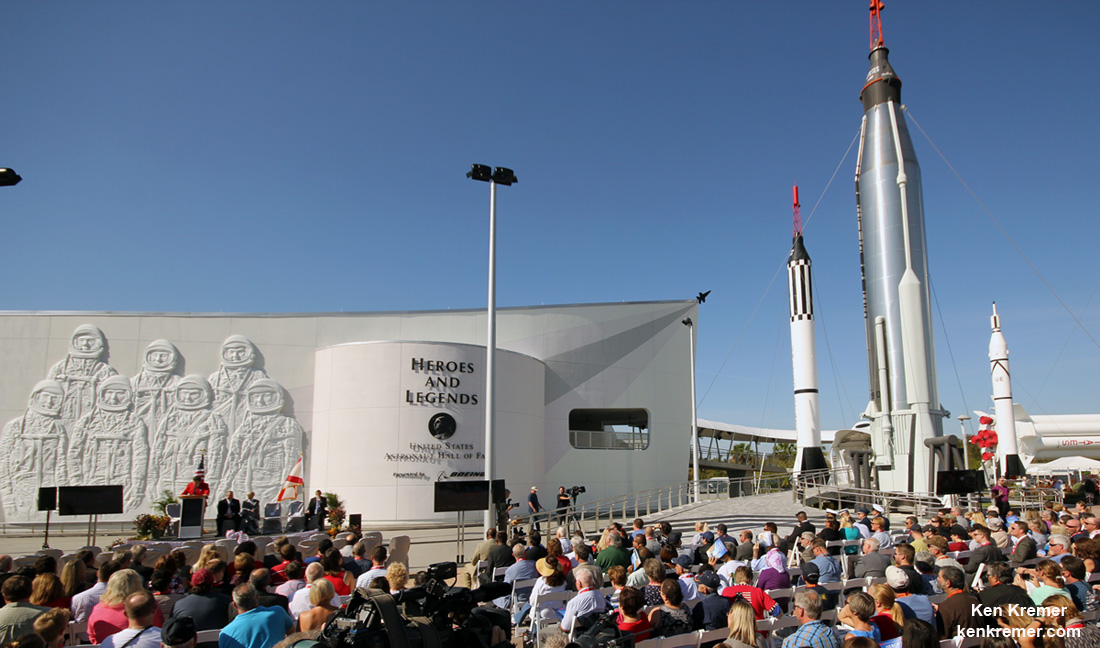

With fanfare and a fireworks display perfectly timed for Veterans Day, ‘Heroes and Legends’ opened its doors to the public on Friday, November 11, 2016, during a gala ceremony attended by more than 25 veteran and current NASA astronauts, including revered Gemini and Apollo space program astronauts Buzz Aldrin, Jim Lovell, Charlie Duke, Tom Stafford, Dave Scott, Walt Cunningham and Al Worden – and throngs of thrilled members of the general public who traveled here as eyewitnesses from all across the globe.

Aldrin, Scott, and Duke walked on the Moon during the Apollo 11, 15 and 16 missions.

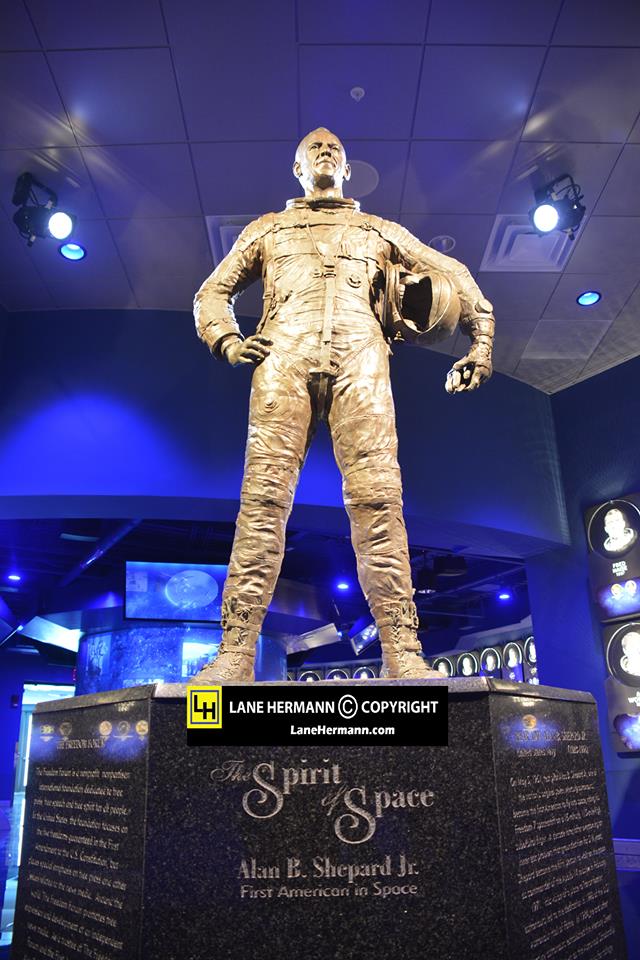

Also on hand were the adult children of the late-astronauts Alan Shepard (first American in space) and Neil Armstrong (first man to walk on the Moon), as well as representatives from NASA, The Boeing Company (sponsor) and park operator Delaware North – for the engaging program hosted by Master of Ceremonies John Zarrella, CNN’s well known and now retired space correspondent.

The stunning new ‘Heroes and Legends’ attraction is perfectly positioned just inside the entrance to the KSC Visitor Complex to greet visitors upon their arrival with an awe inspiring sense of what it was like to embark on the very first human journey’s into space by the pioneers who made it all possible ! And when every step along the way unveiled heretofore unknown treasures into the origin of us and our place in the Universe.

Upon entering the park visitors will immediately and surely be mesmerized by a gigantic bas relief sculpture recreating an iconic photo of America’s first astronauts – the Mercury 7 astronauts; Scott Carpenter, Gordon Cooper, John Glenn, Gus Grissom, Wally Schirra, Alan Shepard, and Deke Slayton.

“With all the drama of an actual trip to space, guests of Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex in Florida will be greeted with a dramatic sense of arrival with the new Heroes & Legends featuring the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame® presented by Boeing. Positioned just inside the entrance, the attraction sets the stage for a richer park experience by providing the emotional background and context for space exploration and the legendary men and women who pioneered our journey into space,” according to a description from Delaware North Companies Parks and Resorts, which operates the KSC visitor complex.

“Designed to be the first stop upon entering Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex, Heroes & Legends uses the early years of the space program to explore the concept of heroism, and the qualities that define the individuals who inspired their generation.”

“I hope that all of you, when you get to see Heroes and Legends, you’re inspired,” said Kennedy Space Center Director Bob Cabana, a former space shuttle astronaut and member of the Astronaut Hall of Fame, during the ceremony.

“The children today can see that there is so much more they can reach for if they apply themselves and do well.”

“I think people a thousand years from now are going to be happy to see these artifacts and relics,” Apollo 15 command module pilot Al Worden told the crowd.

“We have so much on display here with a Saturn V, Space Shuttle Atlantis. People will think back and see the wonderful days we had here. And I guess in that same vein, that makes me a relic too.”

Furthermore, ‘Heroes and Legends’ is now very conveniently housed inside the new home of the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame (AHOF) – making for a unified space exploration experience for park visitors. AHOF previously was located at another off site park facility some seven miles outside and west of the Visitor Complex.

The bas relief measures 30 feet tall and 40 feet wide. It is made put of fiberglass and was digitally sculpted, carved by CNC machines and juts out from the side of the new into the new 37,000 square foot U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame (AHOF) structure.

To date 93 astronauts have been inducted into the Astronaut Hall of Fame spanning the Mercury, Gemini, Apollo and Space Shuttle programs.

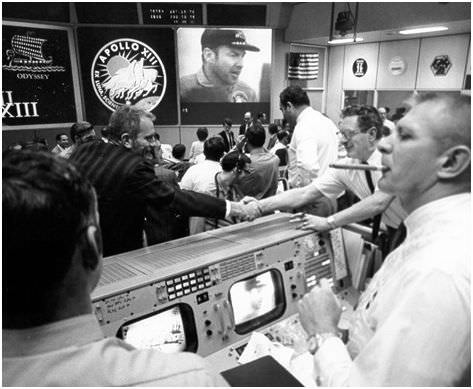

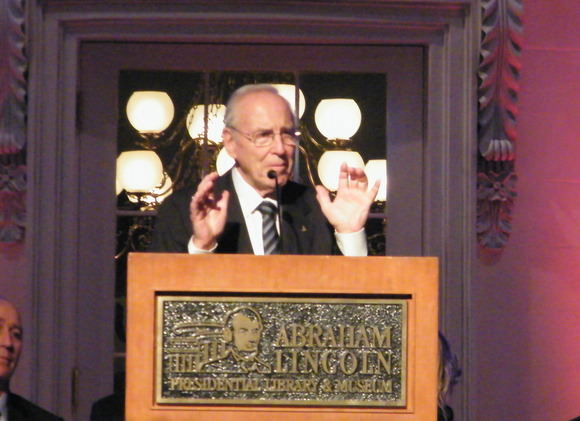

“I don’t consider myself a hero like say, Charles Lindbergh,” said Jim Lovell, a member of the Astronaut Hall of Fame and Apollo 13 commander, when asked by Zarrella what it feels like to be considered an American space hero. “I just did what was proper and exciting — something for my country and my family. I guess I’m just a lucky guy.”

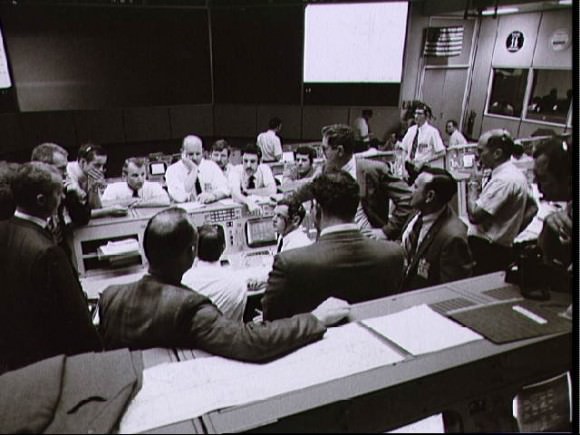

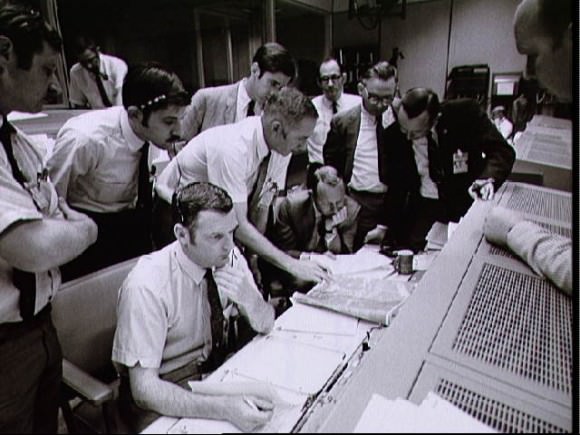

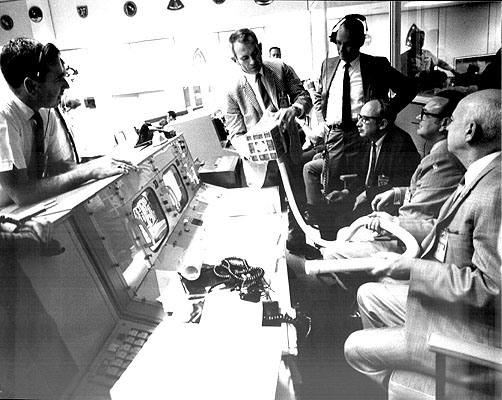

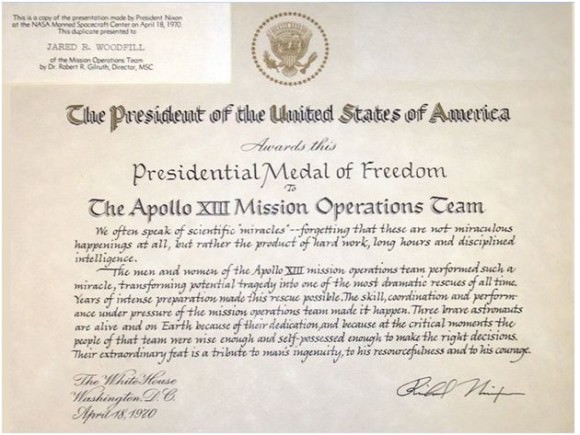

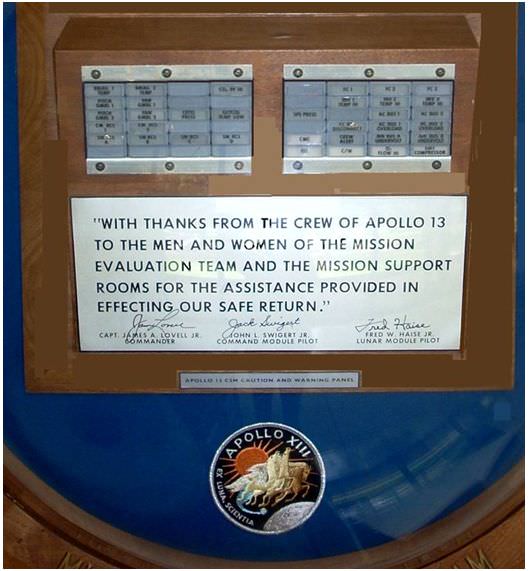

The astronauts are also quick to say that they were supported by hundreds of thousands of dedicated people working in the space program to make Apollo happen.

“It important to remember all the dedication and hard work that it took from those of us involved in the astronaut program, but also the support we received from Kennedy and all the contractors involved in Apollo,” said Apollo 16 moonwalker Charlie Duke.

“400,000 people made it possible for 24 of us to go to the Moon.”

“So dream big, aim high!” exclaimed Duke.

“Hopefully this is an inspiration to you and your kids and grandkids.”

Construction of the facility by Falcon’s Treehouse, an Orlando-based design firm began in the fall of 2015.

“We’re focusing on a story to create what we consider a ‘launch pad’ for our visitors,” said Therrin Protze, the Delaware North chief operating officer of the Visitor Complex. “This is an opportunity to learn about the amazing attributes of our heroes behind the historical events that have shaped the way we look at space, the world and the future.

“We are grateful to NASA for allowing us to tell the NASA story to millions of guests from all over the world,” Protze said.

Visitors walk up a sweeping ramp to enter the Heroes and Legends experience.

After visitors walk through the doors, they will be immersed by two successive video presentations and finally the Hall of Fame exhibit hall.

Here’s a detailed description:

• In the stunning 360-degree discovery bay, What is a Hero?, guests will explore how society defines heroism through diverse perspectives. Each examination of heroism starts with the following questions: What is a hero; Who are the heroes of our time; and What does it take to be a hero? During the seven-minute presentation, the historic beginning of the space race is acknowledged as the impetus for America’s push to the stars in NASA’s early years and the rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

• Through the Eyes of a Hero is a custom-built theater featuring a multi-sensory experience during which guests will vicariously join NASA’s heroes and legends on the most perilous stages of their adventures. Artistically choreographed lighting and 3D imagery will be enhanced by intense, deeply resonant sound effects to create the sensation of being “in the moment.” The seven and one-half minute show takes guests on an intimate journey with four space-age heroes to fully immerse them in the awe, excitement and dangers of the first crewed space program missions.

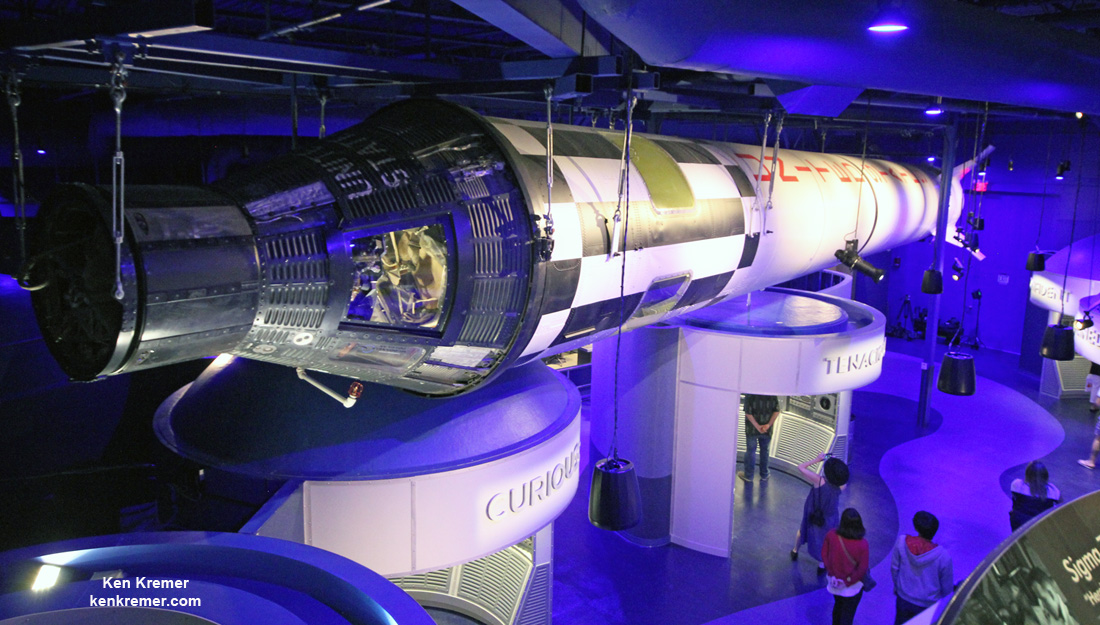

• The third experience, A Hero Is…, offers interactive exhibits that highlight the nine different attributes of our history making astronauts: inspired, curious, passionate, tenacious, disciplined, confident, courageous, principled and selfless. A collection of nine exhibit modules will explore each aforementioned attribute, through the actual experiences of NASA’s astronauts. Their stories are enhanced with memorabilia from the astronaut or the space program.

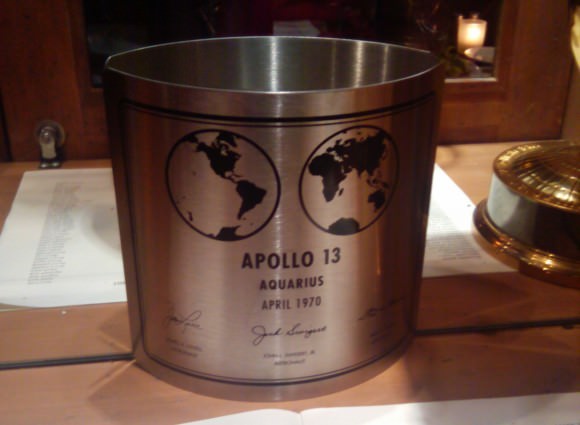

Priceless historic artifacts on display also include two flown capsules from Mercury and Gemini; the Sigma 7 Mercury spacecraft piloted by Wally Schirra during his six-orbit mission in October 1962 and the Gemini IX capsule flown by Tom Stafford and Gene Cernan for three days in June 1966.

The human rated Mercury Redstone-6 (MR-6) is also on display and dramatically mated to the Schirra’s Sigma 7 Mercury capsule.

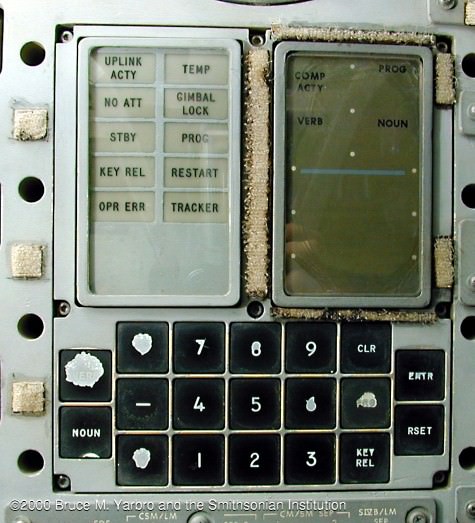

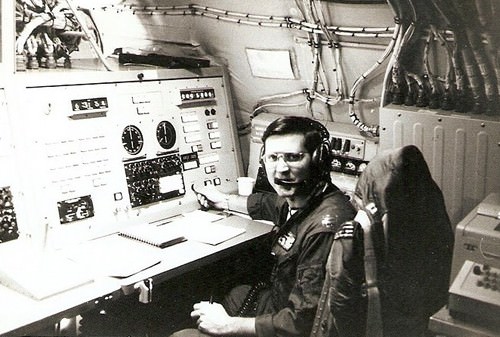

Another room houses the original consoles of the Mercury Mission Control room with the world map that was used to follow the path of John Glenn’s Mercury capsule Friendship 7 between tracking stations when he became the first American to orbit Earth in 1962.

Further details about ‘Heroes and Legends, the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame and all other attractions are available at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex website: https://www.kennedyspacecenter.com/

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and Planetary science and human spaceflight news.

………….

Learn more about Heroes and Legends at KSCVC, GOES-R weather satellite, OSIRIS-REx, InSight Mars lander, SpaceX missions, Juno at Jupiter, SpaceX CRS-9 rocket launch, ISS, ULA Atlas and Delta rockets, Orbital ATK Cygnus, Boeing, Space Taxis, Mars rovers, Orion, SLS, Antares, NASA missions and more at Ken’s upcoming outreach events:

Nov 17-20: “GOES-R weather satellite launch, OSIRIS-REx launch, SpaceX missions/launches to ISS on CRS-9, Juno at Jupiter, ULA Delta 4 Heavy spy satellite, SLS, Orion, Commercial crew, Curiosity explores Mars, Pluto and more,” Kennedy Space Center Quality Inn, Titusville, FL, evenings