Even though the spacecraft has exhausted its supply of liquid helium coolant necessary to observe the infrared energy of the distant Universe, data collected by ESA’s Herschel space observatory are still helping unravel cosmic mysteries — such as how early elliptical galaxies grew so large so quickly, filling up with stars and then, rather suddenly, shutting down star formation altogether.

Now, using information initially gathered by Herschel and then investigating closer with several other space- and ground-based observatories, researchers have found a “missing link” in the evolution of early ellipticals: an enormous star-sparking merging of two massive galaxies, caught in the act when the Universe was but 3 billion years old.

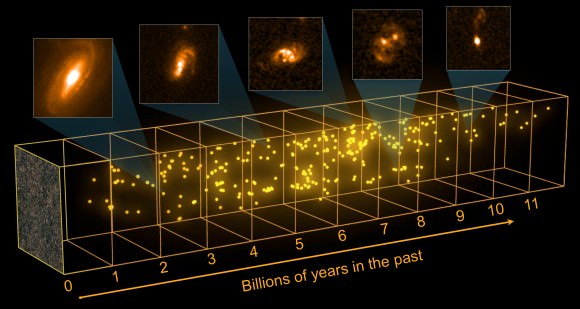

It’s been a long-standing cosmological conundrum: how did massive galaxies form in the early Universe? Observations of distant large elliptical galaxies full of old red stars (and few bright, young ones) existing when the Universe was only a few billion years old just doesn’t line up with how such galaxies were once thought to form — namely, through the gradual accumulation of many smaller dwarf galaxies.

But such a process would take time — much longer than a few billion years. So another suggestion is that massive elliptical galaxies could have been formed by the collision and merging of large galaxies, each full of gas, dust, and new stars… and that the merger would spark a frenzied formation of even more stars.

Investigation of a bright region first found by Herschel, named HXMM01, has identified such a merger of two galaxies, 11 billion light-years distant.

The enormous galaxies are linked by a bridge of gas and each has a stellar mass of about 100 billion Suns — and they are spawning new stars at the incredible rate of about 2,000 a year.

“We’re looking at a younger phase in the life of these galaxies — an adolescent burst of activity that won’t last very long,” said Hai Fu of the University of California at Irvine, lead author of a new study describing the results.

“These merging galaxies are bursting with new stars and completely hidden by dust,” said co-author Asantha Cooray, also of the University of California at Irvine. “Without Herschel’s far-infrared detectors, we wouldn’t have been able to see through the dust to the action taking place behind.”

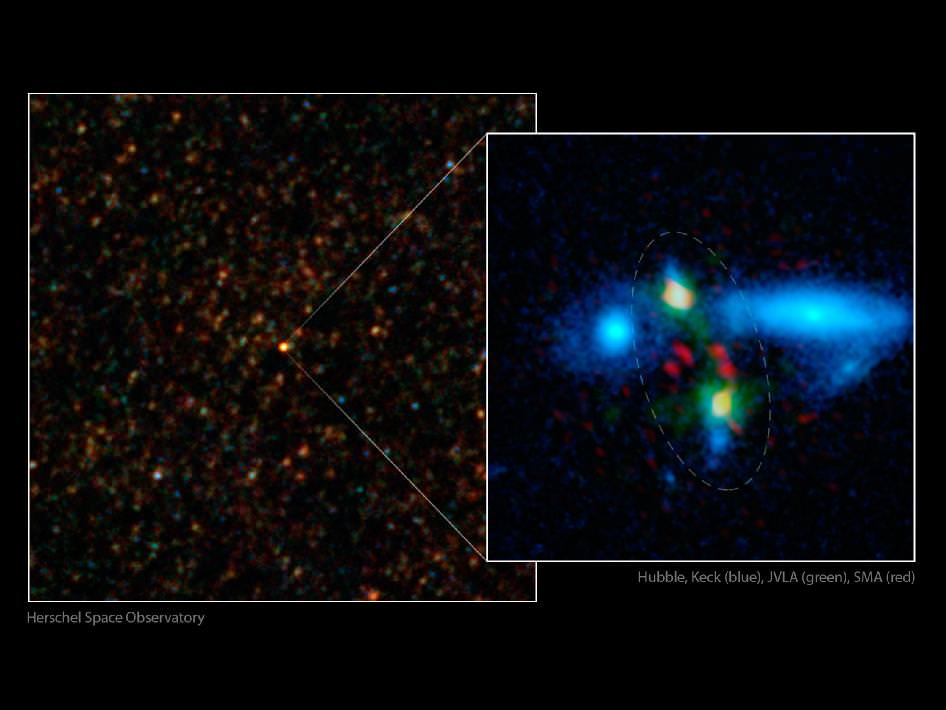

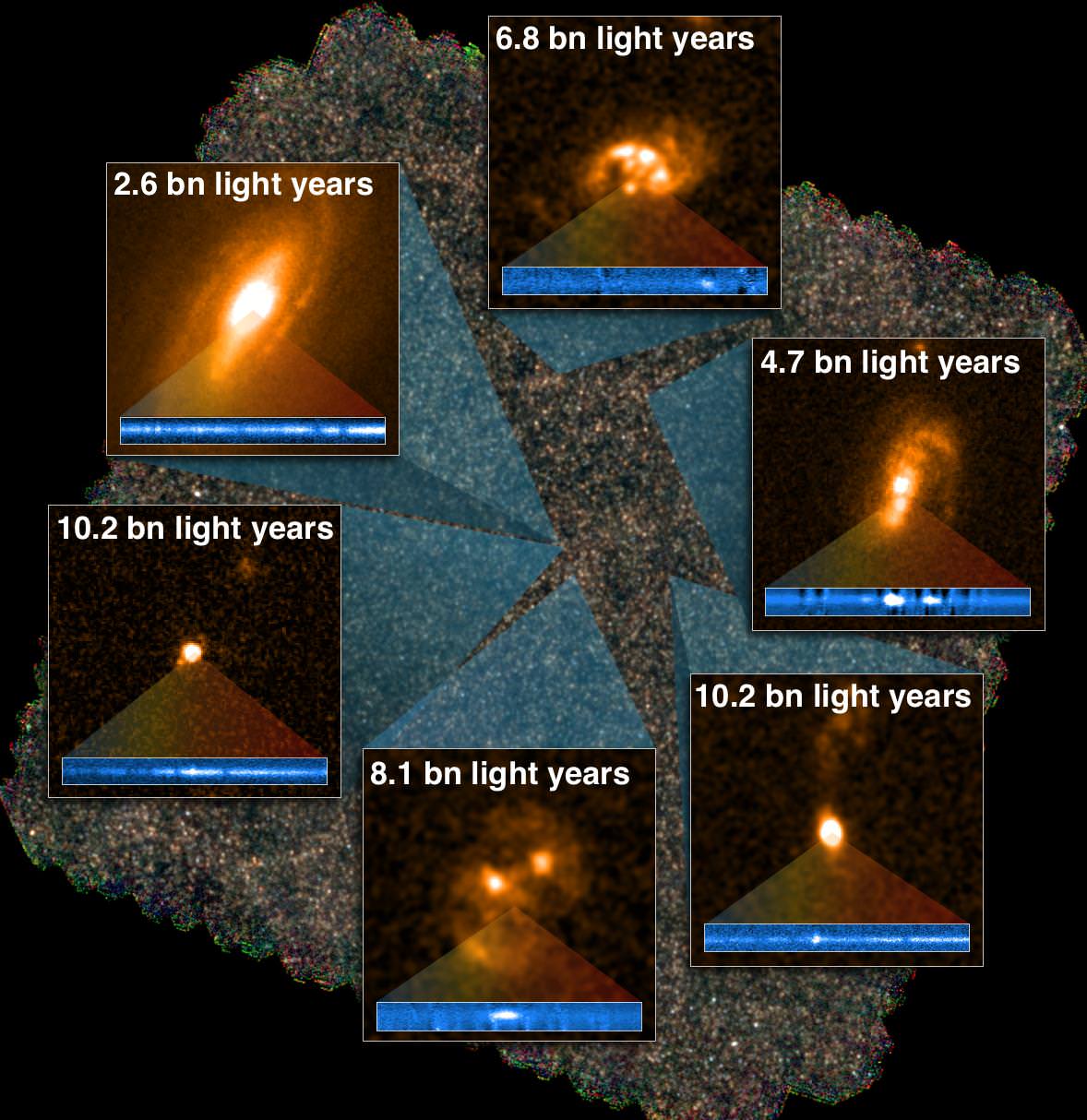

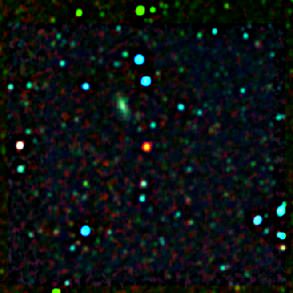

Herschel first spotted the colliding duo in images taken with longer-wavelength infrared light, as shown in the image above on the left side. Follow-up observations from many other telescopes helped determine the extreme degree of star-formation taking place in the merger, as well as its incredible mass.

The image at right shows a close-up view, with the merging galaxies circled. The red data are from the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory’s Submillimeter Array atop Mauna Kea, Hawaii, and show dust-enshrouded regions of star formation. The green data, taken by the National Radio Astronomy Observatory’s Very Large Array, near Socorro, N.M., show carbon monoxide gas in the galaxies. In addition, the blue shows starlight.

Although the galaxies in HXMM01 are producing thousands more new stars each year than our own Milky Way does, such a high star-formation rate is not sustainable. The gas reservoir contained in the system will be quickly exhausted, quenching further star formation and leading to an aging population of low-mass, cool, red stars — effectively “switching off” star formation, like what’s been witnessed in other early ellipticals.

Dr. Fu and his team estimate that it will take about 200 million years to convert all the gas into stars, with the merging process completed within a billion years. The final product will be a massive red and dead elliptical galaxy of about 400 billion solar masses.

The study is published in the May 22 online issue of Nature.

Read more on the ESA Herschel news release here, as well as on the NASA site here. Also, check out an animation of the galactic merger below:

Main image credit: ESA/NASA/JPL-Caltech/UC Irvine/STScI/Keck/NRAO/SAO

The background stars in the image are part of the Small Magellanic Cloud, which was in the distance behind 47 Tucanae when this image was taken.

The background stars in the image are part of the Small Magellanic Cloud, which was in the distance behind 47 Tucanae when this image was taken.

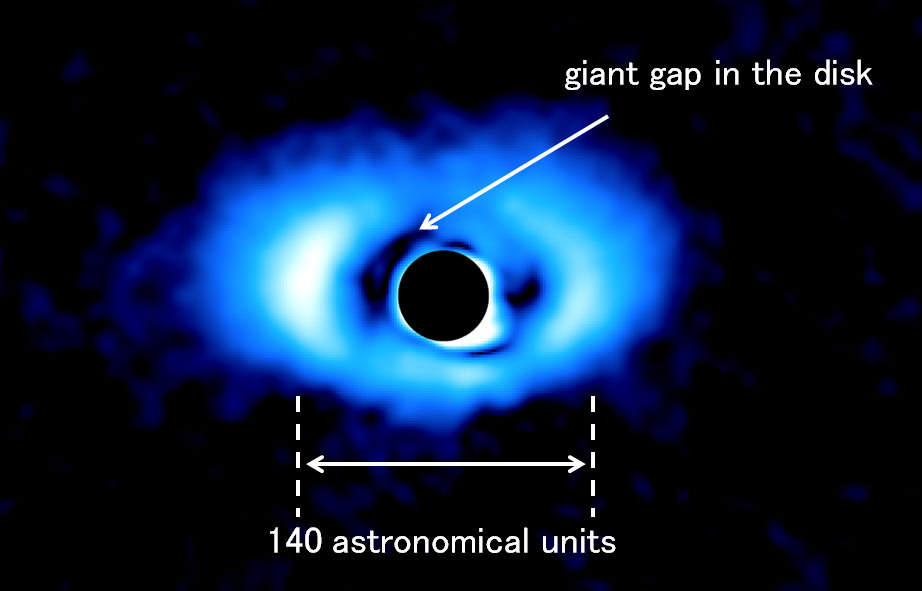

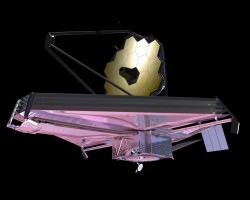

The FGS consists of two identical cameras that are critical to Webb’s ability to “see.” Their images will allow the telescope to determine its position, locate its celestial targets, and remain pointed to collect high-quality data. The FGS will guide the telescope with incredible precision, with an accuracy of one millionth of a degree.

The FGS consists of two identical cameras that are critical to Webb’s ability to “see.” Their images will allow the telescope to determine its position, locate its celestial targets, and remain pointed to collect high-quality data. The FGS will guide the telescope with incredible precision, with an accuracy of one millionth of a degree.