[/caption]

If you take a lot of digital pictures, you’re probably familiar with the frustration of keeping track of dozens of files, and always running out of hard drive space to store them. Well, the scientists and engineers on NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) mission have no pity for you. Their spacecraft just finished photographing the entire sky in exquisite detail: a total of 1.3 million photos.

“The eyes of WISE have not blinked since launch,” said William Irace, the mission’s project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. “Both our telescope and spacecraft have performed flawlessly and have imaged every corner of our universe, just as we planned.”

WISE surveys the sky in strips as it orbits the earth. It takes six months of constant observing to map the entire sky. By pointing at every part of the sky, astronomical surveys deliver excellent data covering both well-known objects and those that have never been seen before.

“WISE is filling in the blanks on the infrared properties of everything in the universe from nearby asteroids to distant quasars,” said Peter Eisenhardt of JPL, project scientist for WISE. “But the most exciting discoveries may well be objects we haven’t yet imagined exist.”

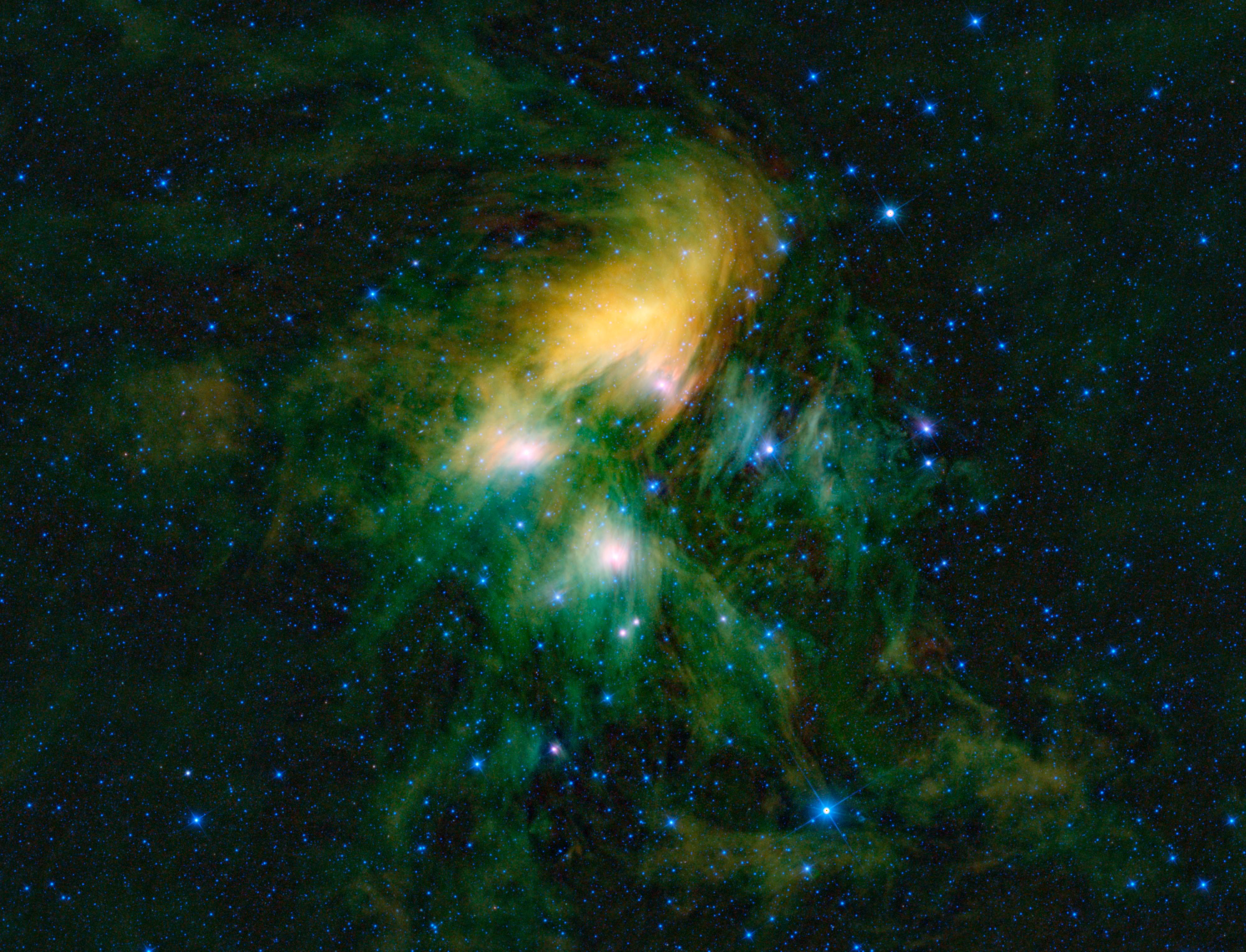

One example of a well-known object seen in new light by WISE is the Pleiades cluster: a group of young blue stars shrouded by dust that the cluster is currently passing through. In WISE’s false-color infrared vision, the hot stars look blue but the cooler dust clouds give off longer wavelengths of infrared light, causing them to glow in shades of yellow and green.

The WISE survey is particularly significant because such a wide range of objects in the universe are visible in infrared light. Giant molecular clouds glow in infrared light, as do brown dwarfs – objects that are bigger than planets but smaller than true stars. WISE can also see ultra-bright, extremely distant galaxies whose visible light has been stretched into the infrared by the expansion of the universe during its multi-billion-year journey.

The recently completed WISE survey also observed 100,000 asteroids in our solar system, many of which had never been seen before. 90 of the newly discovered asteroids are near-earth objects, whose orbits cross our own, making them potentially dangerous but also potential targets for future mission.

You might think that 1.3 million pictures would be plenty, but WISE will keep mapping the sky for another three months, covering half of the sky again and allowing astronomers to search for changes. The mission will end when the spacecraft’s solid hydrogen coolant finally runs out and the infrared detectors warm up (they don’t work as well when they are warm enough to emit the same wavelengths of infrared light that they are meant to detect).

But even as the telescope warms up, the astronomers on the WISE team will just be getting warmed up too. With nearly two million images, they will be busy making new discoveries for years to come.