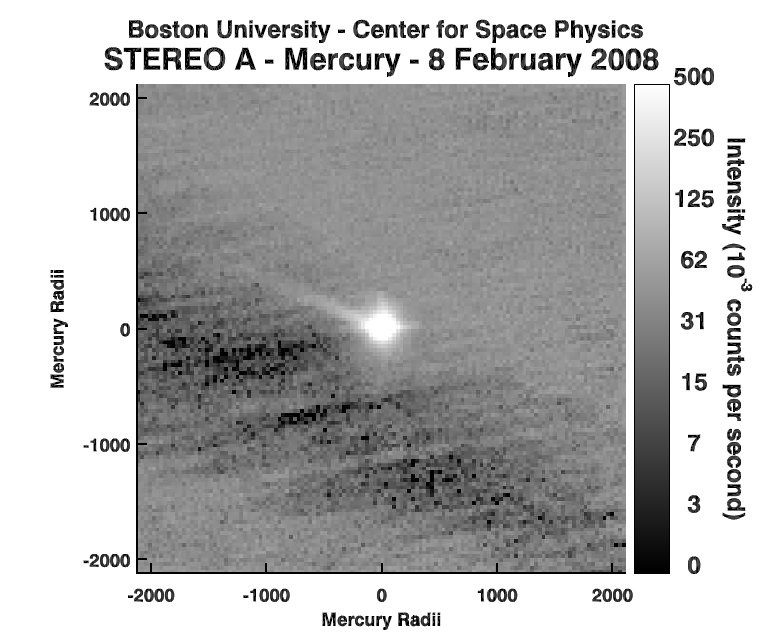

The STEREO mission to study the Sun also has observed some unusual comet-like features exhibited by the planet Mercury, with a coma of tenuous gas surrounding the planet and a very long tail extending away from the sun. These types of features had been seen before from telescopes on Earth, but the STEREO observations are helping scientists to understand the nature of the emissions coming from Mercury, which might be different from what was previously thought.

Another note of interest: the tail in the STEREO data was actually discovered by a fellow blogger, Ian Musgrave, who writes Astroblog. He is a medical researcher in Australia who has a strong interest in astronomy. Viewing the on-line data base of STEREO images and movies, Dr. Musgrave recognized the tail and sent news of it to a team of astronomers from Boston University to compare it with their observations.

[/caption]

The STEREO mission has two satellites placed in the same orbit around the Sun that the Earth has, but at locations ahead and behind it. This configuration offers multi-directional views of the electrons and ions that make up the escaping solar wind. On occasion, the planet Mercury appears in the field of view of one or both satellites. In addition to its appearance as a bright disk of reflected sunlight, a ‘tail’ of emission can be seen in some of the images.

From Earth-based telescopes, astronomers have seen how the Sun’s radiation pressure pushes sodium atoms from Mercury’s surface away from the planet – and away from the Sun – creating a tail that extends many hundreds of times the physical size of Mercury.

Much closer to Mercury, several smaller tails composed of other gases, both neutral and ionized, have been found by NASA’s MESSENGER satellite as it flew by Mercury in its long approach to entering into a stable orbit there.

“We have observed this extended sodium tail to great distances using our telescope at the McDonald Observatory in Texas,” Boston University graduate student Carl Schmidt explained, “and now the tail can also be seen from satellites near Earth.”

“What makes the STEREO detections so interesting is that the brightness levels seem to be too strong to be from sodium,” said Boston University graduate student Carl Schmidt, lead author on a paper that was presented at European Planetary Science Congress in Rome this week.

Now, the Boston University scientists are working with the STEREO scientists to try and sort everything out.

The current focus of the team is to sort out all of the possibilities for the gases that make up the tail. Dr. Christopher Davis from the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in Chilton, England, a member of the STEREO team is working closely with the Boston University group on refining the brightness calibration methods, and determining the precise wavelengths of light that would get through the cameras’ filters.

“The combination of our ground-based data with the new STEREO data is an exciting way to learn as much as possible about the sources and fates of gases escaping from Mercury,” said Michael Mendillo, Professor of Astronomy at Boston University and director of the Imaging Science Lab where the work is being done.

“This is precisely the type of research that makes for a terrific Ph.D. dissertation,” Mendillo added.

Read the team’s paper: “Observations of Mercury’s Escaping Sodium Atmosphere by the STEREO Spacecraft”

Sources: European Planetary Science Congress, Boston University, Astroblog,