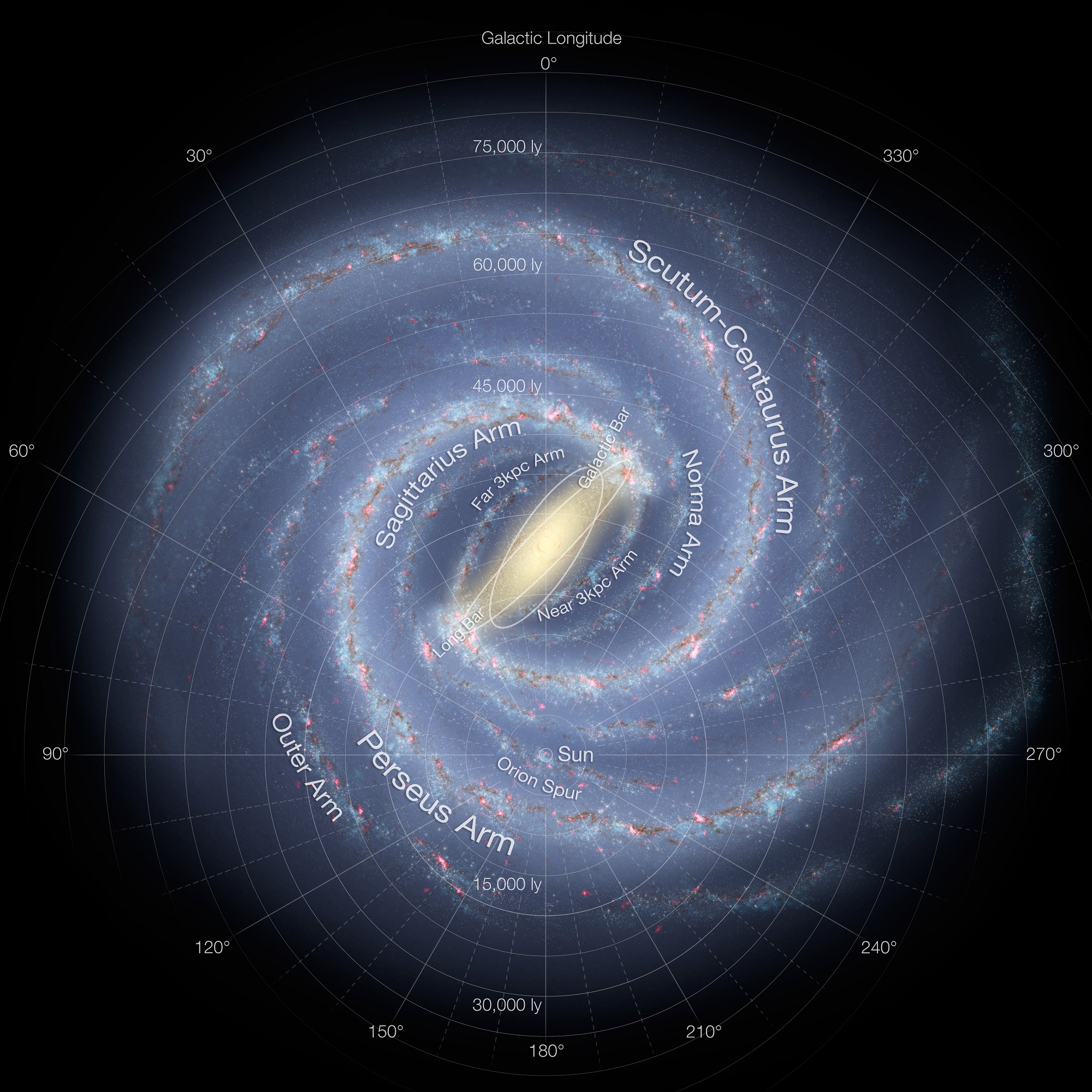

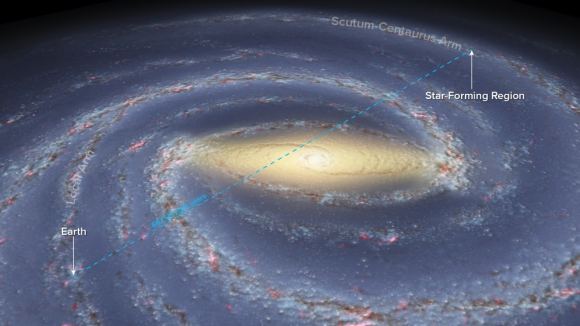

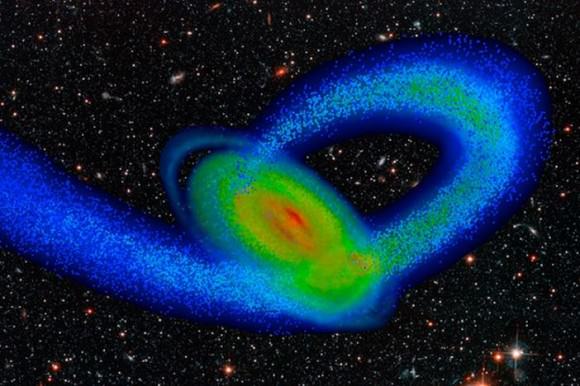

The core of the Milky Way Galaxy has always been a source of mystery and fascination to astronomers. This is due in part to the fact that our Solar System is embedded within the disk of the Milky Way – the flattened region that extends outwards from the core. This has made seeing into the bulge at the center of our galaxy rather difficult. Nevertheless, what we’ve been able to learn over the years has proven to be immensely interesting.

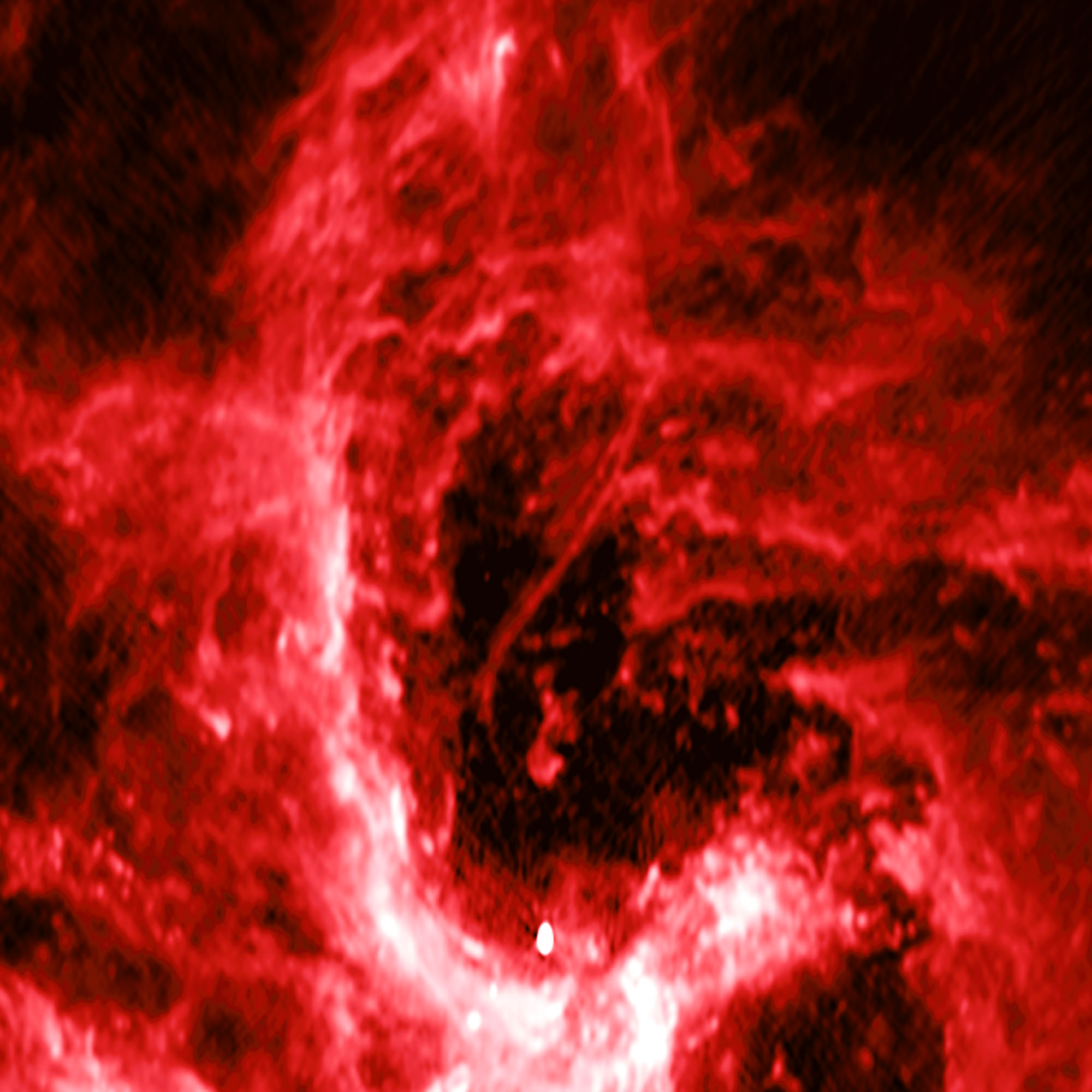

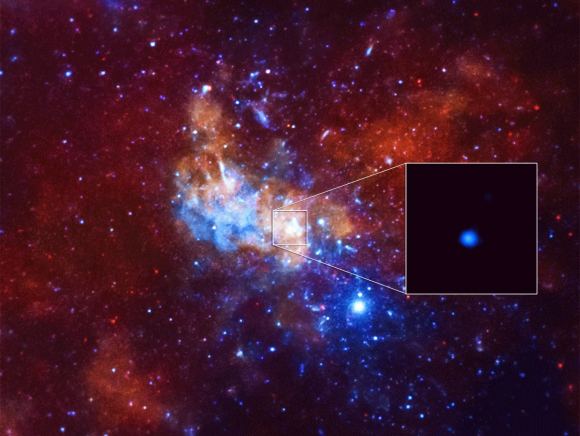

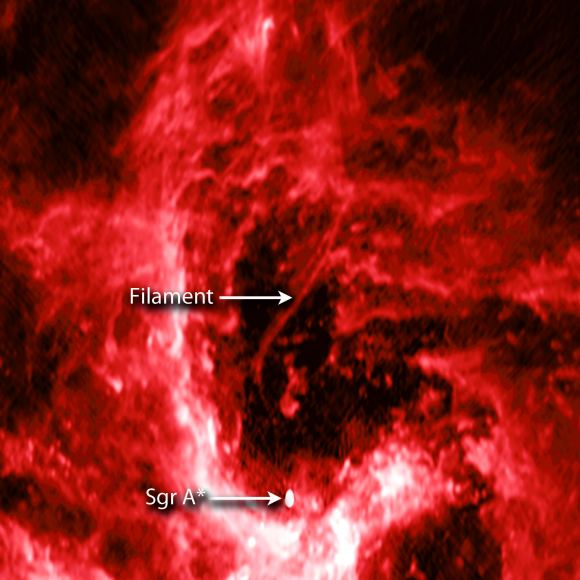

For instance, in the 1970s, astronomers became aware of the Supermassive Black Hole (SMBH) at the center of our galaxy, known as Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*). In 2016, astronomers also noticed a curved filament that appeared to be extending from Sgr A*. Using a pioneering technique, a team of astronomers from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) recently produced the highest-quality images of this structure to date.

The study which details their findings, titled “A Nonthermal Radio Filament Connected to the Galactic Black Hole?“, recently appeared in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. In it, the team describes how they used the National Radio Astronomy Observatory’s (NRAO) Very Large Array to investigate the non-thermal radio filament (NTF) near Sagittarius A* – now known as the Sgr A West Filament (SgrAWF).

As Mark Morris – a professor of astronomy at the UCLA and the lead authority the study – explained in a CfA press release:

“With our improved image, we can now follow this filament much closer to the Galaxy’s central black hole, and it is now close enough to indicate to us that it must originate there. However, we still have more work to do to find out what the true nature of this filament is.”

After examining the filament, the research team came up with three possible explanations for its existence. The first is that the filament is the result of inflowing gas, which would produce a rotating, vertical tower of magnetic field as it approaches and threads Sgr A*’s event horizon. Within this tower, particles would produce radio emissions as they are accelerated and spiral in around magnetic field lines extending from the black hole.

The second possibility is that the filament is a theoretical object known as a cosmic string. These are basically long, extremely thin cosmic structures that carry mass and electric currents that are hypothesized to migrate from the centers of galaxies. In this case, the string could have been captured by Sgr A* once it came too close and a portion crossed its event horizon.

The third and final possibility is that there is no real association between the filament and Sgr A* and the positioning and direction it has shown is merely coincidental. This would imply that there are many such filaments in the Universe and this one just happened to be found near the center of our galaxy. However, the team is confident that such a coincidence is highly unlikely.

As Jun-Hui Zhao of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, and a co-author on the paper, said:

“Part of the thrill of science is stumbling across a mystery that is not easy to solve. While we don’t have the answer yet, the path to finding it is fascinating. This result is motivating astronomers to build next generation radio telescopes with cutting edge technology.”

All of these scenarios are currently being investigated, and each poses its own share of implications. If the first possibility is true – in which the filament is caused by particles being ejected by Sgr A* – then astronomers would be able to gleam vital information about how magnetic fields operate in such an environment. In short, it could show that near an SMBH, magnetic fields are orderly rather than chaotic.

This could be proven by examining particles farther away from Sgr A* to see if they are less energetic than those that are closer to it. The second possibility, the cosmic string theory, could be tested by conducting follow-up observations with the VLA to determine if the position of the filament is shifting and its particles are moving at a fraction of the speed of light.

If the latter should prove to be the case, it would constitute the first evidence that theoretical cosmic strings actually exists. It would also allow astronomers to conduct further tests of General Relativity, examining how gravity works under such conditions and how space-time is affected. The team also noted that, even if the filament is not physically connected to Sgr A*, the bend in the filament is still rather telling.

In short, the bend appears to be coincide with a shock wave, the kind that would be caused by an exploding star. This could mean that one of the massive stars which surrounds Sgr A* exploded in proximity to the filament in the past, producing the necessary shock wave that altered the course of the inflowing gas and its magnetic field. All of these mysteries will be the subject of follow-up surveys conducted with the VLA.

As co-author Miller Goss from the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in New Mexico (and a co-author on the study) said, “We will keep hunting until we have a solid explanation for this object. And we are aiming to next produce even better, more revealing images.”