Gravitational lensing is a concept where dark matter distorts space revealing its presence through its interaction with light. ESA’s Euclid mission is mapping out the gravitational lensing events to chart the large scale structure of the Universe. Euclid is also expected to discover in excess of 170,000 strong gravitational lensing features too. AI is expected to help achieve this goal but machine learning is still in its infancy so human beings are likely to have to confirm each lens candidate.

Continue reading “Euclid Could Find 170,000 Strong Gravitational Lenses”Gravitationally Lensed Supernovae are Another Way to Measure the Expansion of the Universe

Supernova are a fascinating phenomenon and have taught us much about the evolution of stars. The upcoming Nancy Grace Roman telescope will be hunting the elusive combination of supernovae in a gravitational lens system. With its observing field 200 times that of Hubble it stands a much greater chance of success. If sufficient lensed supernovae are found then they could be used to determine the expansion rate of the Universe.

Continue reading “Gravitationally Lensed Supernovae are Another Way to Measure the Expansion of the Universe”Civilizations Could Use Gravitational Lenses to Transmit Power From Star to Star

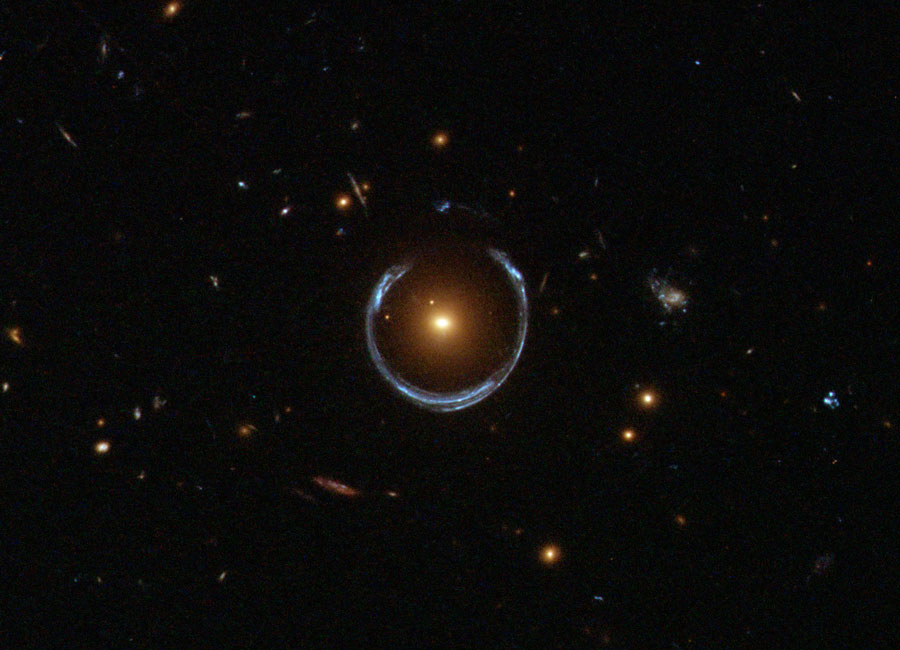

In 1916, famed theoretical physicist Albert Einstein put the finishing touches on his Theory of General Relativity, a geometric theory for how gravity alters the curvature of spacetime. The revolutionary theory remains foundational to our models of how the Universe formed and evolved. One of the many things GR predicted was what is known as gravitational lenses, where objects with massive gravitational fields will distort and magnify light coming from more distant objects. Astronomers have used lenses to conduct deep-field observations and see farther into space.

In recent years, scientists like Claudio Maccone and Slava Turyshev have explored how using our Sun as a Solar Gravity Lens (SGL) could have tremendous applications for astronomy and the Search for Extratterstiral Intelligence (SETI). Two notable examples include studying exoplanets in extreme detail or creating an interstellar communication network (a “galactic internet”). In a recent paper, Turyshev proposes how advanced civilizations could use stellar gravitational lenses to transmit power from star to star – a possibility that could have significant implications in our search for technosignatures.

Continue reading “Civilizations Could Use Gravitational Lenses to Transmit Power From Star to Star”A Huge New Gaia Data Release: More Stars, Gravitational Lenses and Asteroids

The ESA’s Gaia mission is releasing a new tranche of astronomical data. The mission has released three regular, massive hauls of data since it launched in 2013, named Gaia DR1, DR2, and DR3. The ESA is calling this one a ‘focused product release,’ and while it’s smaller than the previous three releases, it’s still impactful.

Continue reading “A Huge New Gaia Data Release: More Stars, Gravitational Lenses and Asteroids”This JWST Image Shows Gravitational Lensing at its Finest

One of the more intriguing aspects of the cosmos, which the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has allowed astronomers to explore, is the phenomenon known as gravitational lenses. As Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity describes, the curvature of spacetime is altered by the presence of massive objects and their gravity. This effect leads to objects in space (like galaxies or galaxy clusters) altering the path light travels from more distant objects (and amplifying it as well). By taking advantage of this with a technique known as Gravitational Lensing, astronomers can study distant objects in greater detail.

Consider the image above, the ESA’s picture of the month acquired by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). The image shows a vast gravitational lens caused by SDSS J1226+2149, a galaxy cluster located roughly 6.3 billion light-years from Earth in the constellation Coma Berenices. The lens these galaxies created greatly amplified light from the more distant Cosmic Seahorse galaxy. Combined with Webb‘s incredible sensitivity, this technique allowed astronomers to study the Cosmic Seahorse in the hopes of learning more about star formation in early galaxies.

Continue reading “This JWST Image Shows Gravitational Lensing at its Finest”A New Record! Hubble Detects an Individual Star From a Time When the Universe Was Less Than a Billion Years Old

A star that sounds as if it came from “The Lord of the Rings” now marks one of the Hubble Space Telescope’s farthest frontiers: The fuzzy point of light, known as Earendel, has been dated to a mere 900 million years after the Big Bang and appears to represent the farthest-out individual star seen to date.

Based on its redshift value of 6.2, Earendel’s light has taken 12.9 billion years to reach Earth, astronomers report in this week’s issue of the journal Nature. That distance mark outshines Hubble’s previous record-holder for a single star, which registered a redshift of 1.5 and is thought to have existed when the universe was 4 billion years old.

The newly reported record comes with caveats. First of all, we’re talking here about a single star rather than star clusters or galaxies. Hubble has seen agglomerations of stars that go back farther in time.

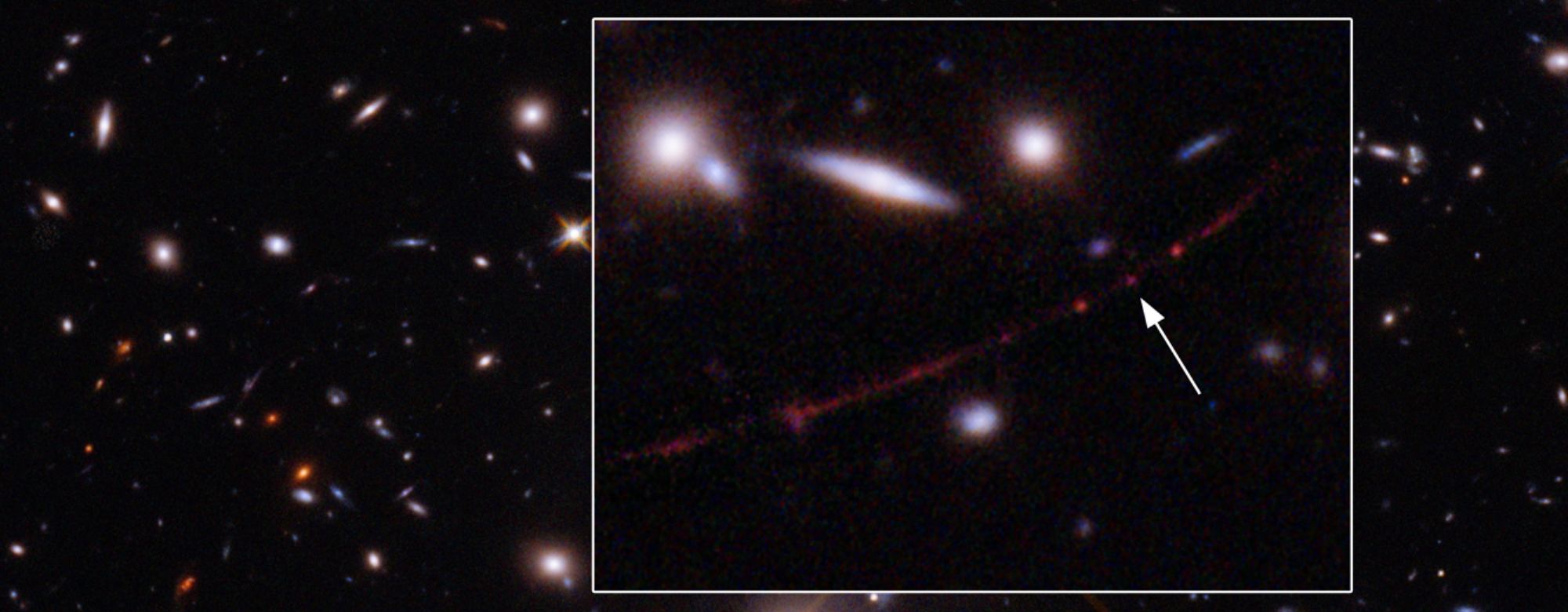

“Normally at these distances, entire galaxies look like small smudges, with the light from millions of stars blending together,” lead author Brian Welch, an astronomer at Johns Hopkins University, said today in a news release. “The galaxy hosting this star has been magnified and distorted by gravitational lensing into a long crescent that we named the Sunrise Arc.”

A close look at the arc turned up several bright spots, but the characteristics of the light coming from Earendel pointed to a high redshift, which translates into extreme distance. The higher the redshift, the faster the source of the light is receding from us in an ever-more-quickly expanding universe.

Continue reading “A New Record! Hubble Detects an Individual Star From a Time When the Universe Was Less Than a Billion Years Old”If We Used the Sun as a Gravitational Lens Telescope, This is What a Planet at Proxima Centauri Would Look Like

As Einstein originally predicted with his General Theory of Relativity, gravity alters the curvature of spacetime. As a consequence, the passage of light changes as it encounters a gravitational field, which is how General Relativity was confirmed! For decades, astronomers have taken advantage of this to conduct Gravitational Lensing (GL) – where a distant source is focused and amplified by a massive object in the foreground.

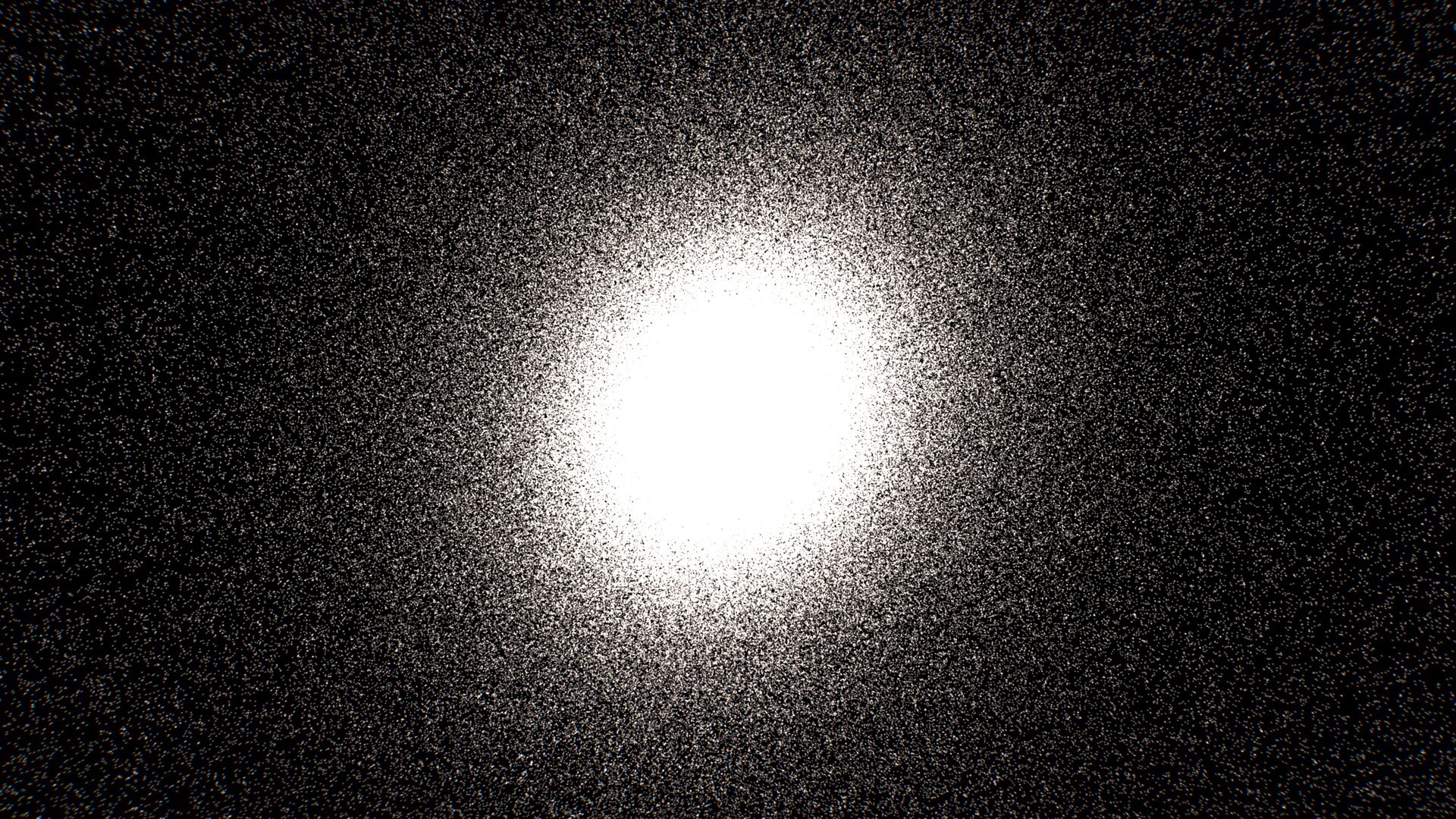

In a recent study, two theoretical physicists argue that the Sun could be used in the same way to create a Solar Gravitational Lens (SGL). This powerful telescope, they argue, would provide enough light amplification to allow for Direct Imaging studies of nearby exoplanets. This could allow astronomers to determine if planets like Proxima b are potentially-habitable long before we send missions to study them.

Continue reading “If We Used the Sun as a Gravitational Lens Telescope, This is What a Planet at Proxima Centauri Would Look Like”Advanced Civilizations Could be Communicating with Neutrino Beams. Transmitted by Clouds of Satellites Around Neutron Stars or Black Holes

In 1960, famed theoretical physicist Freeman Dyson made a radical proposal. In a paper titled “Search for Artificial Stellar Sources of Infrared Radiation” he suggested that advanced extra-terrestrial intelligences (ETIs) could be found by looking for signs of artificial structures so large, they encompassed entire star systems (aka. megastructures). Since then, many scientists have come up with their own ideas for possible megastructures.

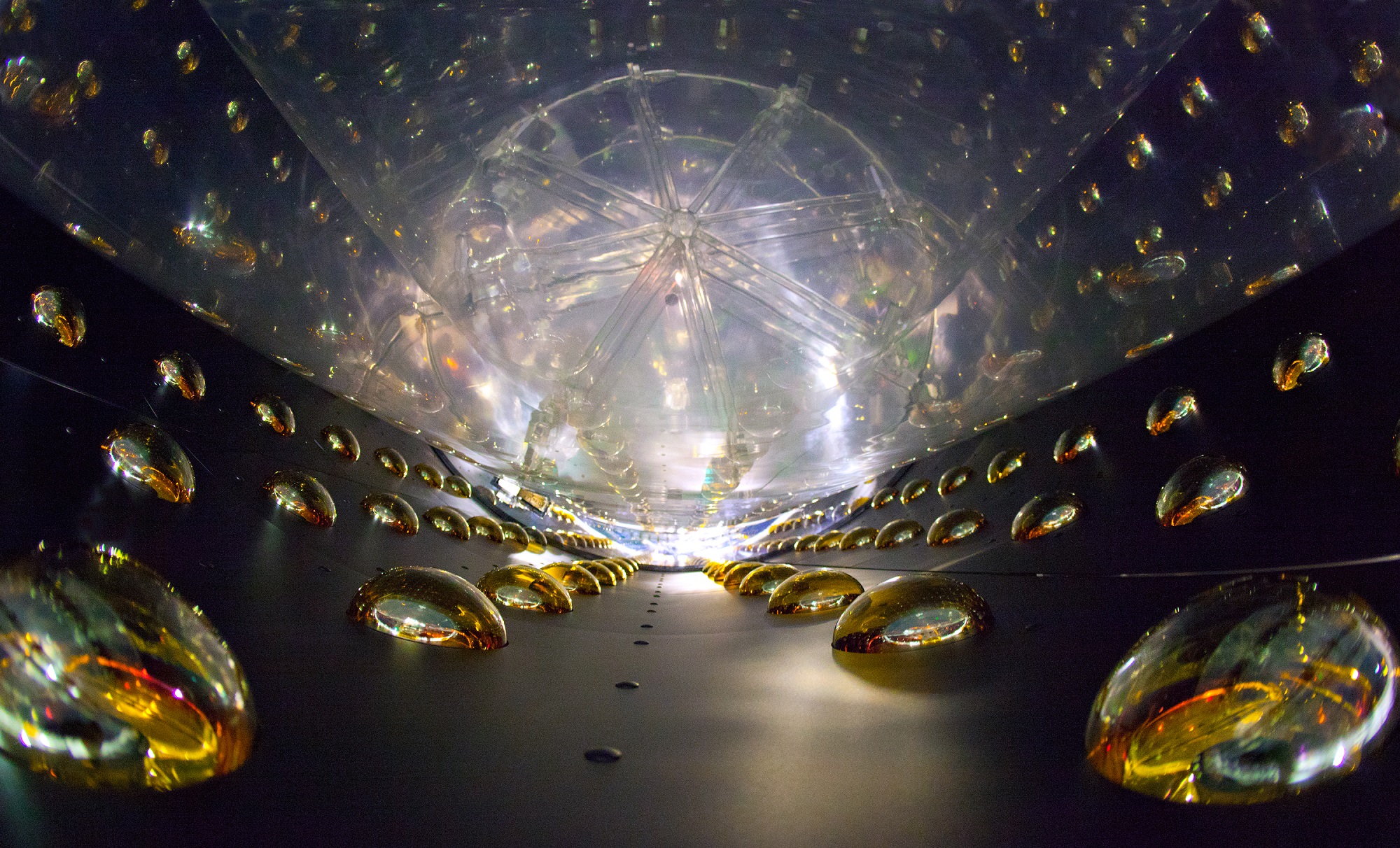

Like Dyson’s proposed Sphere, these ideas were suggested as a way of giving scientists engaged in the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence (SETI) something to look for. Adding to this fascinating field, Dr. Albert Jackson of the Houston-based technology company Triton Systems recently released a study where he proposed how an advanced ETI could use rely on a neutron star or black hole to focus neutrino beams to create a beacon.

Continue reading “Advanced Civilizations Could be Communicating with Neutrino Beams. Transmitted by Clouds of Satellites Around Neutron Stars or Black Holes”Quasars with a Double-Image Gravitational Lens Could Help Finally Figure out how Fast the Universe is Expanding

How fast is the Universe expanding? That’s a question that astronomers haven’t been able to answer accurately. They have a name for the expansion rate of the Universe: The Hubble Constant, or Hubble’s Law. But measurements keep coming up with different values, and astronomers have been debating back and forth on this issue for decades.

The basic idea behind measuring the Hubble Constant is to look at distant light sources, usually a type of supernovae or variable stars referred to as ‘standard candles,’ and to measure the red-shift of their light. But no matter how astronomers do it, they can’t come up with an agreed upon value, only a range of values. A new study involving quasars and gravitational lensing might help settle the issue.

Continue reading “Quasars with a Double-Image Gravitational Lens Could Help Finally Figure out how Fast the Universe is Expanding”Thanks to a Gravitational Lens, Astronomers Can See an Individual Star 9 Billion Light-Years Away

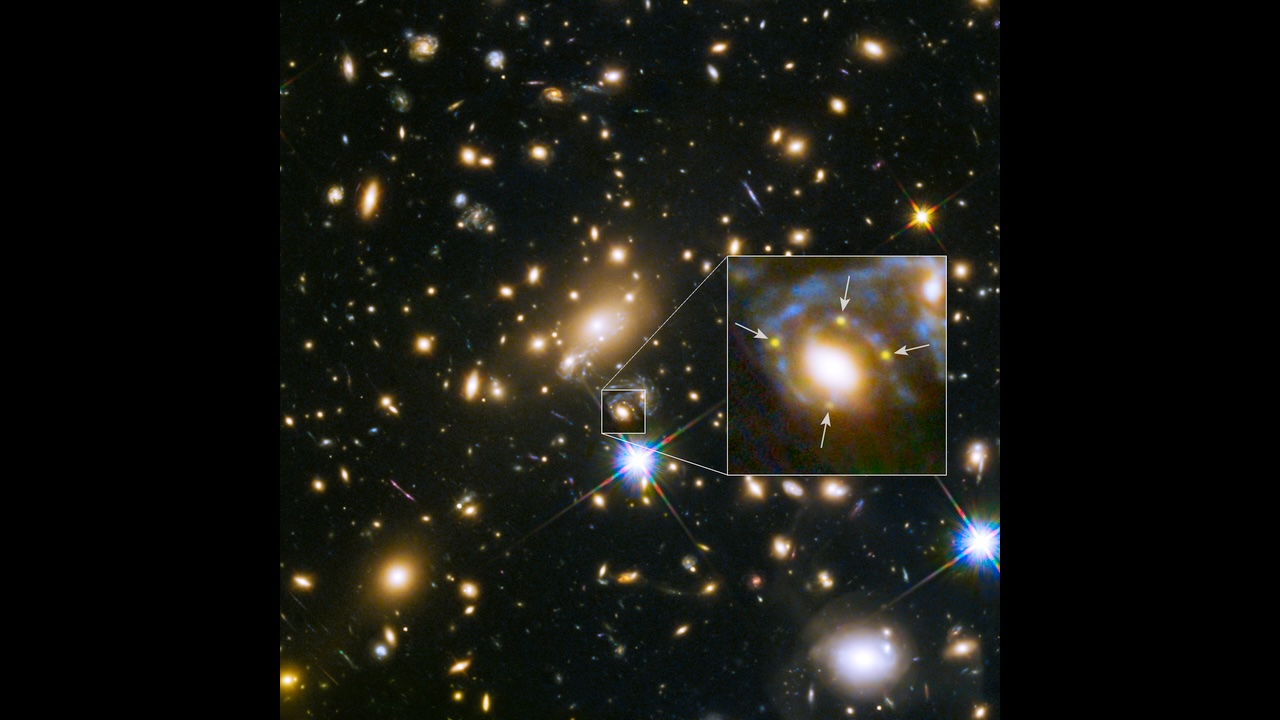

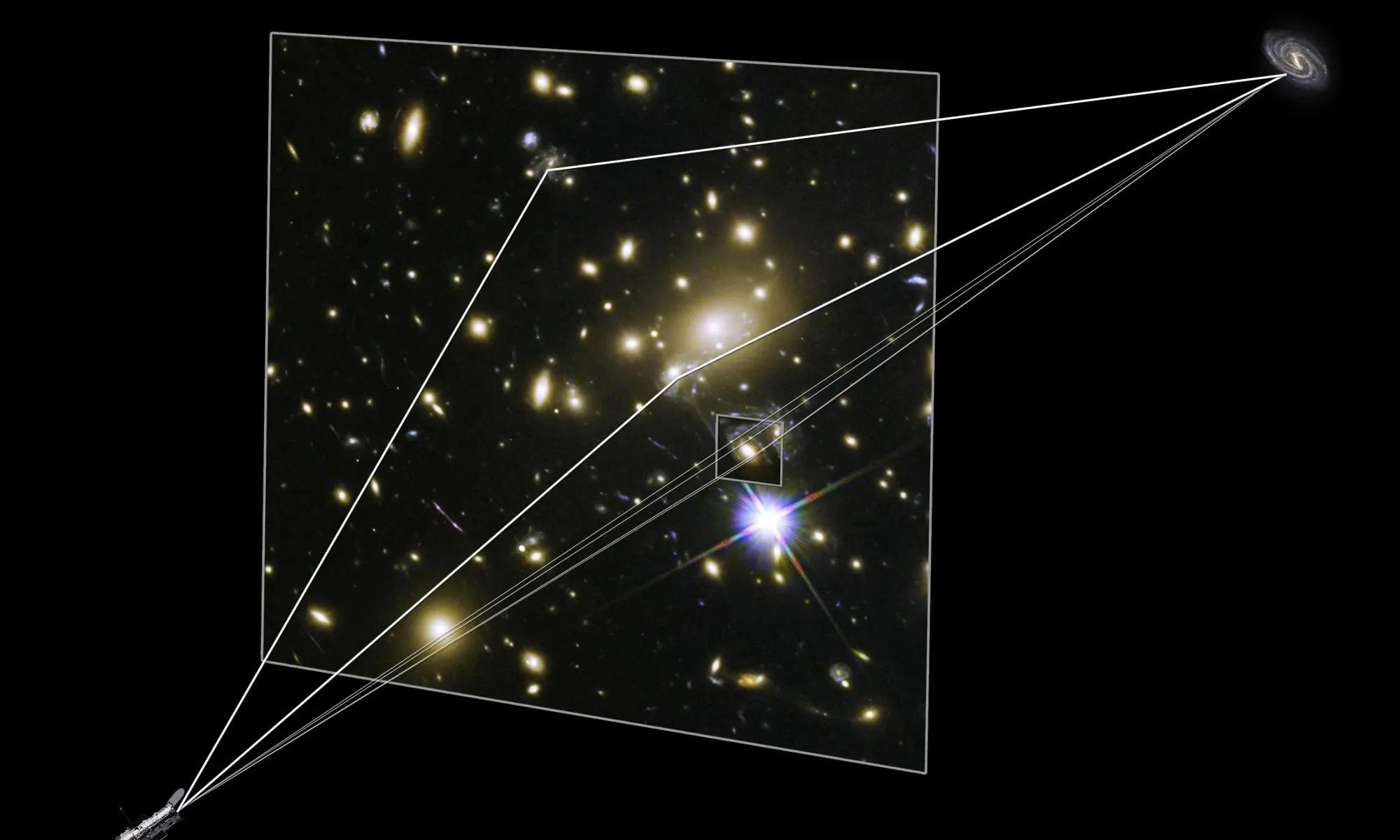

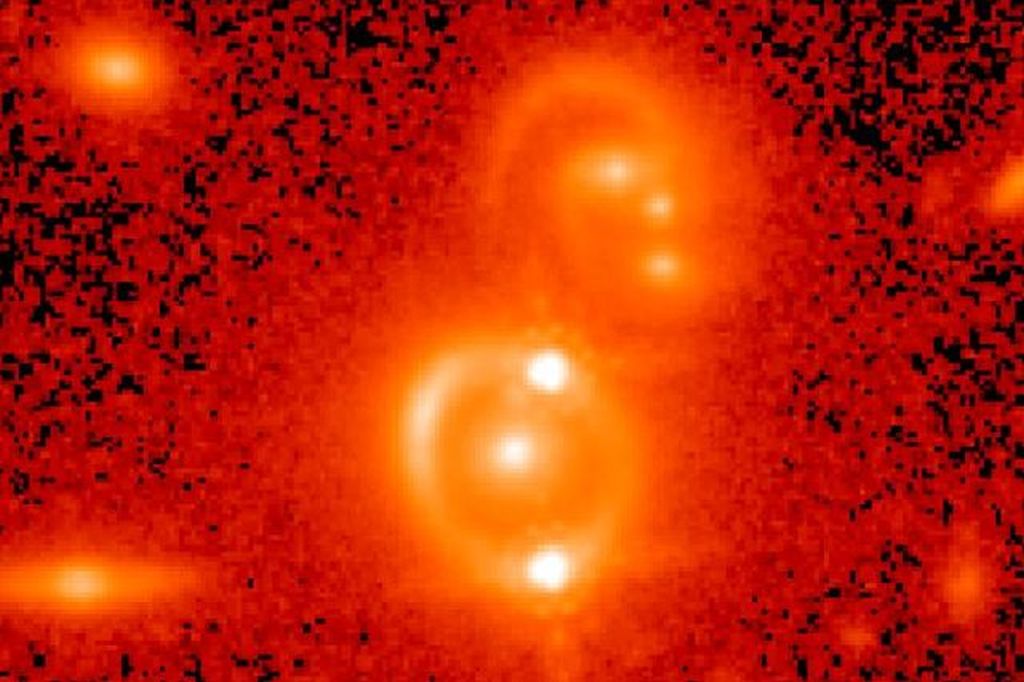

When looking to study the most distant objects in the Universe, astronomers often rely on a technique known as Gravitational Lensing. Based on the principles of Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity, this technique involves relying on a large distribution of matter (such as a galaxy cluster or star) to magnify the light coming from a distant object, thereby making it appear brighter and larger.

This technique has allowed for the study of individual stars in distant galaxies. In a recent study, an international team of astronomers used a galaxy cluster to study the farthest individual star ever seen in the Universe. Although it normally to faint to observe, the presence of a foreground galaxy cluster allowed the team to study the star in order to test a theory about dark matter.

The study which describes their research recently appeared in the scientific journal Nature Astronomy under the title “Extreme magnification of an individual star at redshift 1.5 by a galaxy-cluster lens“. The study was led by Patrick L. Kelly, an assistant professor the University of Minnesota, and included members from the Las Cumbres Observatory, the National Optical Astronomical Observatory, the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), the Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne (EPFL), and multiple universities and research institutions.

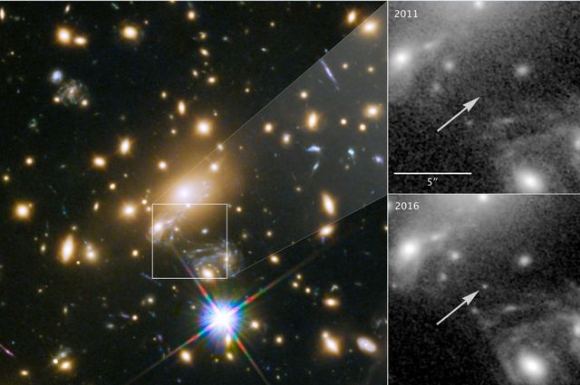

For the sake of their study, Prof. Kelly and his associates used the galaxy cluster known as MACS J1149+2223 as their lens. Located about 5 billion light-years from Earth, this galaxy cluster sits between the Solar System and the galaxy that contains Icarus. By combining Hubble’s resolution and sensitivity with the strength of this gravitational lens, the team was able to see and study Icarus, a blue giant.

Icarus, named after the Greek mythological figure who flew too close to the Sun, has had a rather interesting history. At a distance of roughly 9 billion light-years from Earth, the star appears to us as it did when the Universe was just 4.4 billion years old. In April of 2016, the star temporarily brightened to 2,000 times its normal luminosity thanks to the gravitational amplification of a star in MACS J1149+2223.

As Prof. Kelly explained in a recent UCLA press release, this temporarily allowed Icarus to become visible for the first time to astronomers:

“You can see individual galaxies out there, but this star is at least 100 times farther away than the next individual star we can study, except for supernova explosions.”

Kelly and a team of astronomers had been using Hubble and MACS J1149+2223 to magnify and monitor a supernova in the distant spiral galaxy at the time when they spotted the new point of light not far away. Given the position of the new source, they determined that it should be much more highly magnified than the supernova. What’s more, previous studies of this galaxy had not shown the light source, indicating that it was being lensed.

As Tommaso Treu, a professor of physics and astronomy in the UCLA College and a co-author of the study, indicated:

“The star is so compact that it acts as a pinhole and provides a very sharp beam of light. The beam shines through the foreground cluster of galaxies, acting as a cosmic magnifying glass… Finding more such events is very important to make progress in our understanding of the fundamental composition of the universe.

In this case, the star’s light provided a unique opportunity to test a theory about the invisible mass (aka. “dark matter”) that permeates the Universe. Basically, the team used the pinpoint light source provided by the background star to probe the intervening galaxy cluster and see if it contained huge numbers of primordial black holes, which are considered to be a potential candidate for dark matter.

These black holes are believed to have formed during the birth of the Universe and have masses tens of times larger than the Sun. However, the results of this test showed that light fluctuations from the background star, which had been monitored by Hubble for thirteen years, disfavor this theory. If dark matter were indeed made up of tiny black holes, the light coming from Icarus would have looked much different.

Since it was discovered in 2016 using the gravitational lensing method, Icarus has provided a new way for astronomers to observe and study individual stars in distant galaxies. In so doing, astronomers are able to get a rare and detailed look at individual stars in the early Universe and see how they (and not just galaxies and clusters) evolved over time.

When the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is deployed in 2020, astronomers expect to get an even better look and learn so much more about this mysterious period in cosmic history.

Further Reading: UCLA