Incoming: The Earth-Moon system has company tonight.

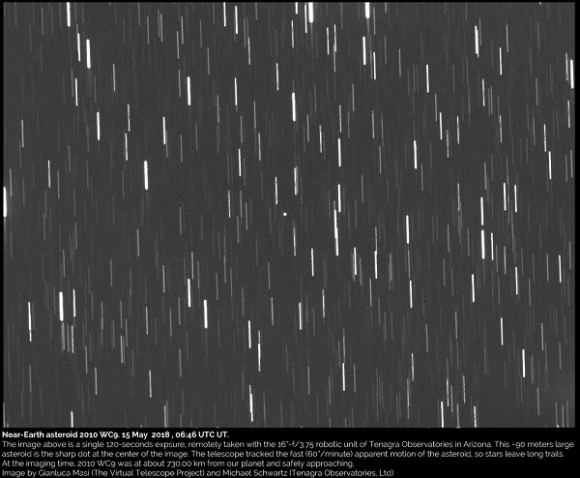

The Asteroid: Near Earth Asteroid 2010 WC9 is back. Discovered by the Catalina Sky Survey outside Tucson, Arizona on November 30th, 2010, this asteroid was lost after a brief 10 day observation window and was not recovered until just earlier this month. About 71 meters in size, 2010 WC9 is one of the largest asteroids to pass us closer than the Earth-Moon distance.

2010 WC9 poses no threat to the Earth. About the size of the Statue of Liberty from the ground level to her crown, the asteroid is over three times bigger than the one that exploded over Chelyabinsk, Russia on the morning of February 15th, 2013.

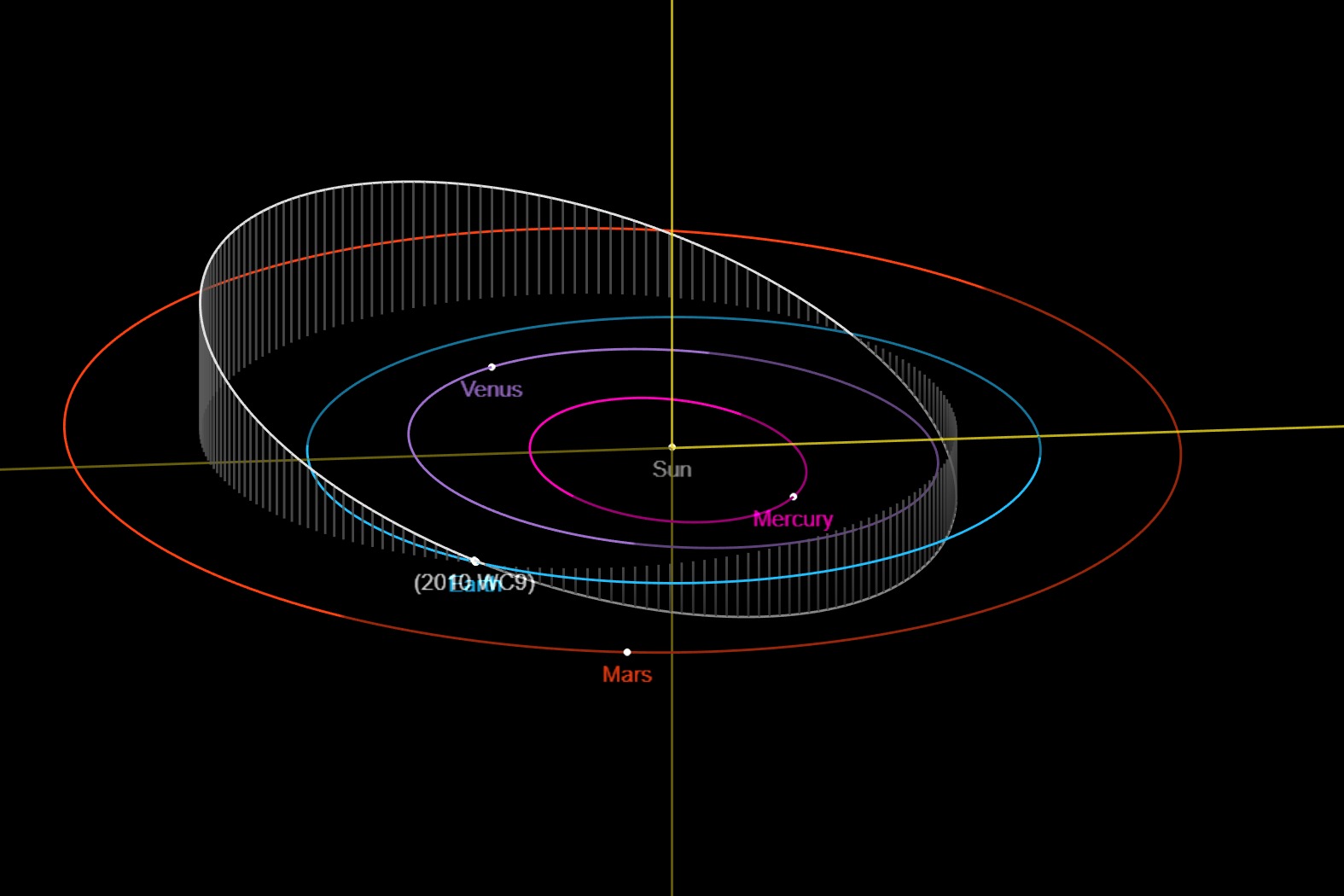

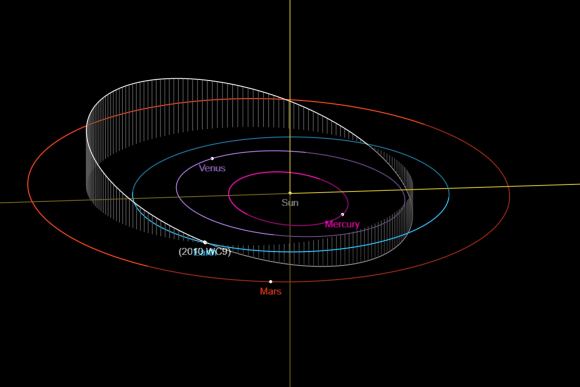

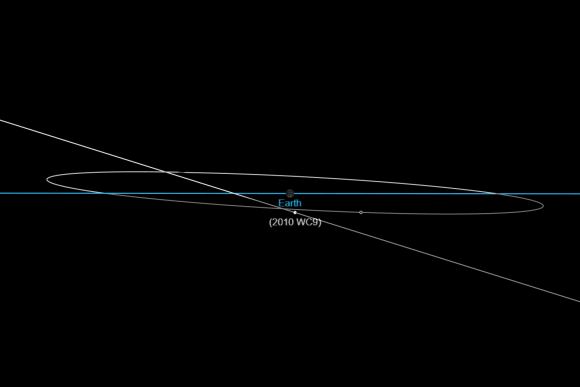

The Pass: 2010 WC9 passes just 0.5 times the Earth-Moon distance (126,500 miles or 203,500 kilometers) on Tuesday, May 15th at 22:05 UT/6:05 PM EDT. That’s only roughly five times the distance of satellites in geosynchronous orbit. The asteroid is also a relative fast mover, whizzing by at over 12 kilometers per second. An Apollo-type asteroid, 2010 WC9 orbits the Sun once every 409 days, ranging from a perihelion of 0.78 astronomical units (AU) outside the orbit of Venus out to 1.38 AU, just inside the orbit of Mars. This is the closest passage of the asteroid by the Earth for this century.

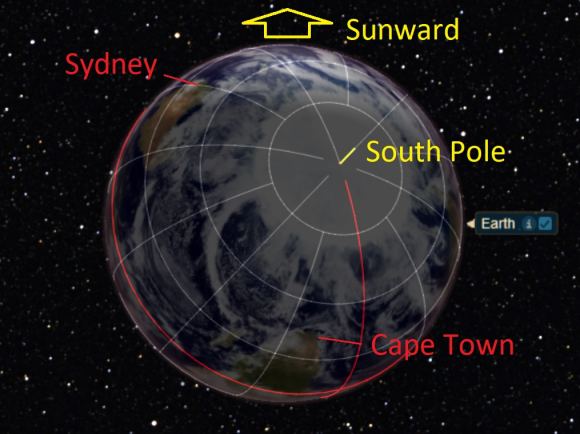

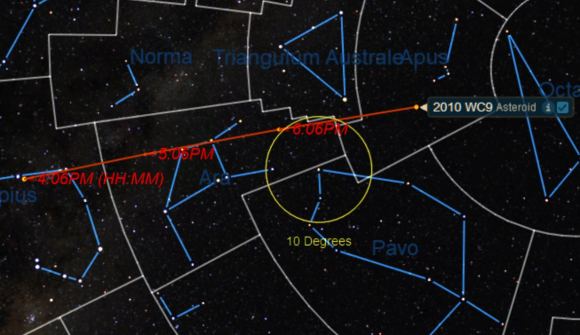

Observing: This one grabbed our attention when it cropped up on the Space Weather page for close asteroid passes this past weekend: a large, fast mover passing close to the Earth is a true rarity. At closest approach, 2010 WC9 will be moving at 0.22 degrees (that’s 13 arcminutes, about half the span of a Full Moon) per minute through the constellation Pavo the Peacock shining at magnitude +10, making it a good telescopic object for observers based in South Africa as it heads over the South Pole.

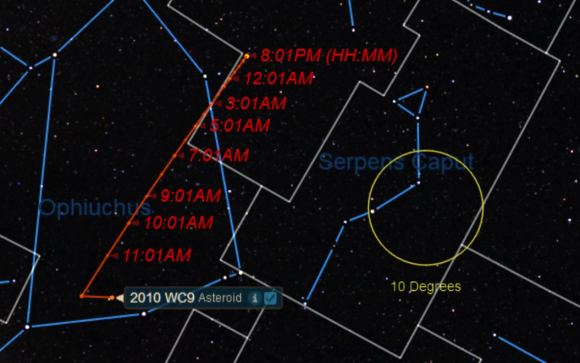

North American and European observers get their best look at the asteroid tonight into early tomorrow morning while it’s still twice the distance of the Moon, shining at 13th magnitude and moving southward through the constellation Ophiuchus and across the ecliptic plane.

The best strategy to ambush the space rock is to simply aim a low power field of view at the right coordinates at the right time (see below), and watch. You should be able to see the asteroid moving slowly against the starry background, in real time.

Keep in mind, the charts we made here are geocentric, assuming you’re observing from the center of the Earth. Parallax comes into play on a close asteroid pass, and the Earth’s gravity will deflect 2010 WC9’s orbit considerably. Your best bet for generating a refined track for the asteroid is to use NASA JPL’s Horizons web interface to generate Right Ascension/Declination coordinates for the 2010 WC9 for your location.

How do you ‘lose an asteroid?” Often, an initial observation arc for a distant asteroid is too short to pin down a refined orbit. We have a blind spot sunward, for example, and fast moving asteroids can also be difficult to track across rich star fields and movement from one celestial hemisphere to the next. Recovery of 2010 WC9 earlier this month now gives us a solid seven year observation arc to peg its orbit down to a high accuracy.

Clouded out, or live in the wrong hemisphere? Slooh will carry an observing session for 2010 WC9 starting tonight at 24:00 UT/ 8:00 PM EDT. The Northholt Branch Observatories in London, England will also stream the pass live via Facebook tonight. Check their page for a start time.

There’s no word yet if Arecibo radar plans to ping 2010 WC9 over the coming days, but if they do, so expect to see an animation soon.

Don’t miss tonight’s passage of 2010 WC9 near the Earth, either in person or online.