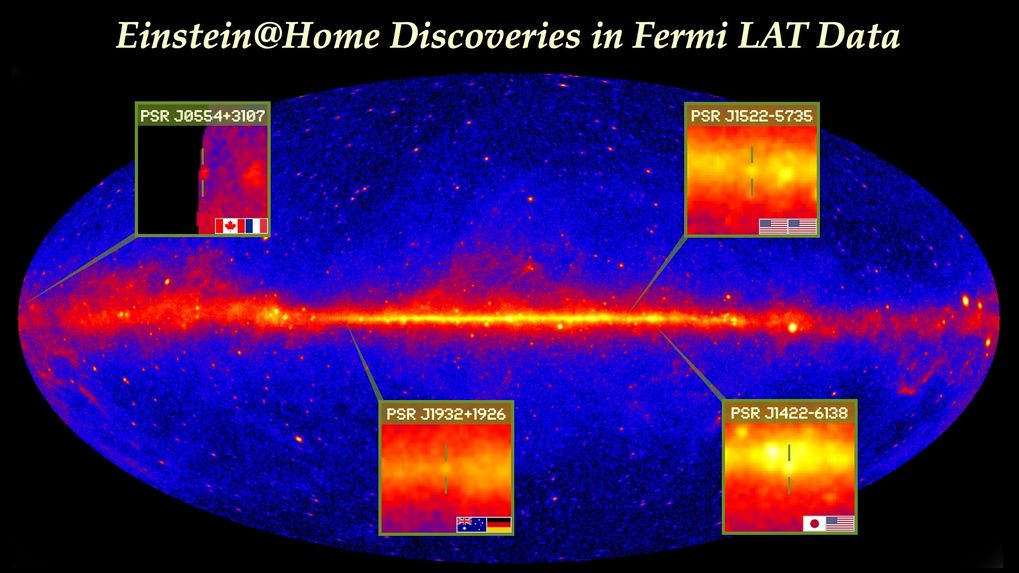

Imagine that you’re innocently running your computer in pursuit of helping data crunch a huge science project. Then, out of the thousands of machines running the project, yours happens to stumble across a discovery. That’s what happened to several volunteers with Einstein@Home, which seeks pulsars in data from the Fermi Gamma-Ray Space Telescope, among other projects.

“At first I was a bit dumbfounded and thought someone was playing a hoax on me. But after I did some research,” everything checked out. That someone as insignificant as myself could make a difference was amazing,” stated Kentucky resident Thomas M. Jackson, who contributed to the project.

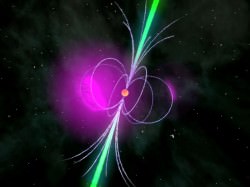

Pulsars, a type of neutron star, are the leftovers of stars that exploded as supernovae. They rotate rapidly, with such precision in their rotation periods that they have sometimes been likened to celestial clocks. Although the discovery is exciting to the eight volunteers because they are the first to find these gamma-ray pulsars as part of a volunteer computing project, the pulsars also have some interesting scientific features.

The four pulsars were discovered in the plane of the Milky Way in an area that radio telescopes had looked at previously, but weren’t able to find themselves. This means that the pulsars are likely only visible in gamma rays, at least from the vantage point of Earth; the objects emit their radiation in a narrow direction with radio, but a wider stripe with gamma rays. (After the discoveries, astronomers used the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy’s 100-meter Effelsberg radio telescope and the Australian Parkes Observatory to peer at those spots in the sky, and still saw no radio signals.)

Two of the pulsars also “hiccup” or exhibit a pulsar glitch, when the rotation sped up and then fell back to the usual rotation period a few weeks later. Astronomers are still learning more about these glitches, but they do know that most of them happen in young pulsars. All four pulsars are likely between 30,000 and 60,000 years old.

“The first-time discovery of gamma-ray pulsars by Einstein@Home is a milestone – not only for us but also for our project volunteers. It shows that everyone with a computer can contribute to cutting-edge science and make astronomical discoveries,” stated co-author Bruce Allen, principal investigator of Einstein@Home. “I’m hoping that our enthusiasm will inspire more people to help us with making further discoveries.”

Einstein@Home is run jointly by the Center for Gravitation and Cosmology at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee and the Albert Einstein Institute in Hannover, Germany. It is funded by the National Science Foundation and the Max Planck Society. As for the volunteers, their names were mentioned in the scientific literature and they also received certificates of discovery for their work.