[/caption]

Published in 1915, Einstein’s theory of general relativity (GR) passed its first big test just a few years later, when the predicted gravitational deflection of light passing near the Sun was observed during the 1919 solar eclipse.

In 1960, GR passed its first big test in a lab, here on Earth; the Pound-Rebka experiment. And over the nine decades since its publication, GR has passed test after test after test, always with flying colors (check out this review for an excellent summary).

But the tests have always been within the solar system, or otherwise indirect.

Now a team led by Princeton University scientists has tested GR to see if it holds true at cosmic scales. And, after two years of analyzing astronomical data, the scientists have concluded that Einstein’s theory works as well in vast distances as in more local regions of space.

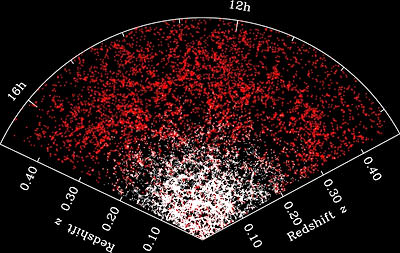

The scientists’ analysis of more than 70,000 galaxies demonstrates that the universe – at least up to a distance of 3.5 billion light years from Earth – plays by the rules set out by Einstein in his famous theory. While GR has been accepted by the scientific community for over nine decades, until now no one had tested the theory so thoroughly and robustly at distances and scales that go way beyond the solar system.

Reinabelle Reyes, a Princeton graduate student in the Department of Astrophysical Sciences, along with co-authors Rachel Mandelbaum, an associate research scholar, and James Gunn, the Eugene Higgins Professor of Astronomy, outlined their assessment in the March 11 edition of Nature.

Other scientists collaborating on the paper include Tobias Baldauf, Lucas Lombriser and Robert Smith of the University of Zurich and Uros Seljak of the University of California-Berkeley.

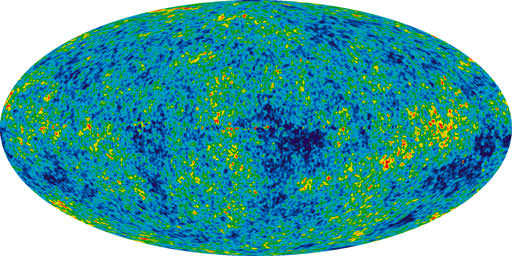

The results are important, they said, because they shore up current theories explaining the shape and direction of the universe, including ideas about dark energy, and dispel some hints from other recent experiments that general relativity may be wrong.

“All of our ideas in astronomy are based on this really enormous extrapolation, so anything we can do to see whether this is right or not on these scales is just enormously important,” Gunn said. “It adds another brick to the foundation that underlies what we do.”

GR is one, of two, core theories underlying all of contemporary astrophysics and cosmology (the other is the Standard Model of particle physics, a quantum theory); it explains everything from black holes to the Big Bang.

In recent years, several alternatives to general relativity have been proposed. These modified theories of gravity depart from general relativity on large scales to circumvent the need for dark energy, dark matter, or both. But because these theories were designed to match the predictions of general relativity about the expansion history of the universe, a factor that is central to current cosmological work, it has become crucial to know which theory is correct, or at least represents reality as best as can be approximated.

“We knew we needed to look at the large-scale structure of the universe and the growth of smaller structures composing it over time to find out,” Reyes said. The team used data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), a long-term, multi-institution telescope project mapping the sky to determine the position and brightness of several hundred million galaxies and quasars.

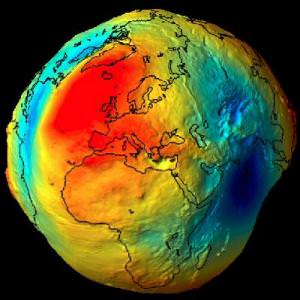

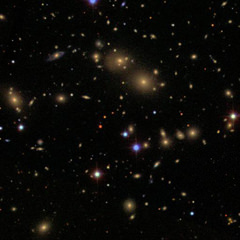

By calculating the clustering of these galaxies, which stretch nearly one-third of the way to the edge of the universe, and analyzing their velocities and distortion from intervening material – due to weak lensing, primarily by dark matter – the researchers have shown that Einstein’s theory explains the nearby universe better than alternative theories of gravity.

The Princeton scientists studied the effects of gravity on the SDSS galaxies and clusters of galaxies over long periods of time. They observed how this fundamental force drives galaxies to clump into larger collections of galaxies and how it shapes the expansion of the universe.

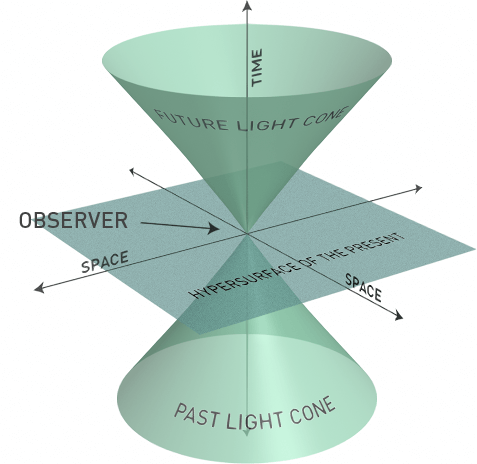

Critically, because relativity calls for the curvature of space to be equal to the curvature of time, the researchers could calculate whether light was influenced in equal amounts by both, as it should be if general relativity holds true.

“This is the first time this test was carried out at all, so it’s a proof of concept,” Mandelbaum said. “There are other astronomical surveys planned for the next few years. Now that we know this test works, we will be able to use it with better data that will be available soon to more tightly constrain the theory of gravity.”

Firming up the predictive powers of GR can help scientists better understand whether current models of the universe make sense, the scientists said.

“Any test we can do in building our confidence in applying these very beautiful theoretical things but which have not been tested on these scales is very important,” Gunn said. “It certainly helps when you are trying to do complicated things to understand fundamentals. And this is a very, very, very fundamental thing.”

“The nice thing about going to the cosmological scale is that we can test any full, alternative theory of gravity, because it should predict the things we observe,” said co-author Uros Seljak, a professor of physics and of astronomy at UC Berkeley and a faculty scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory who is currently on leave at the Institute of Theoretical Physics at the University of Zurich. “Those alternative theories that do not require dark matter fail these tests.”

Sources: “Princeton scientists say Einstein’s theory applies beyond the solar system” (Princeton University), “Study validates general relativity on cosmic scale, existence of dark matter” (University of California Berkeley), “Confirmation of general relativity on large scales from weak lensing and galaxy velocities” (Nature, arXiv preprint)