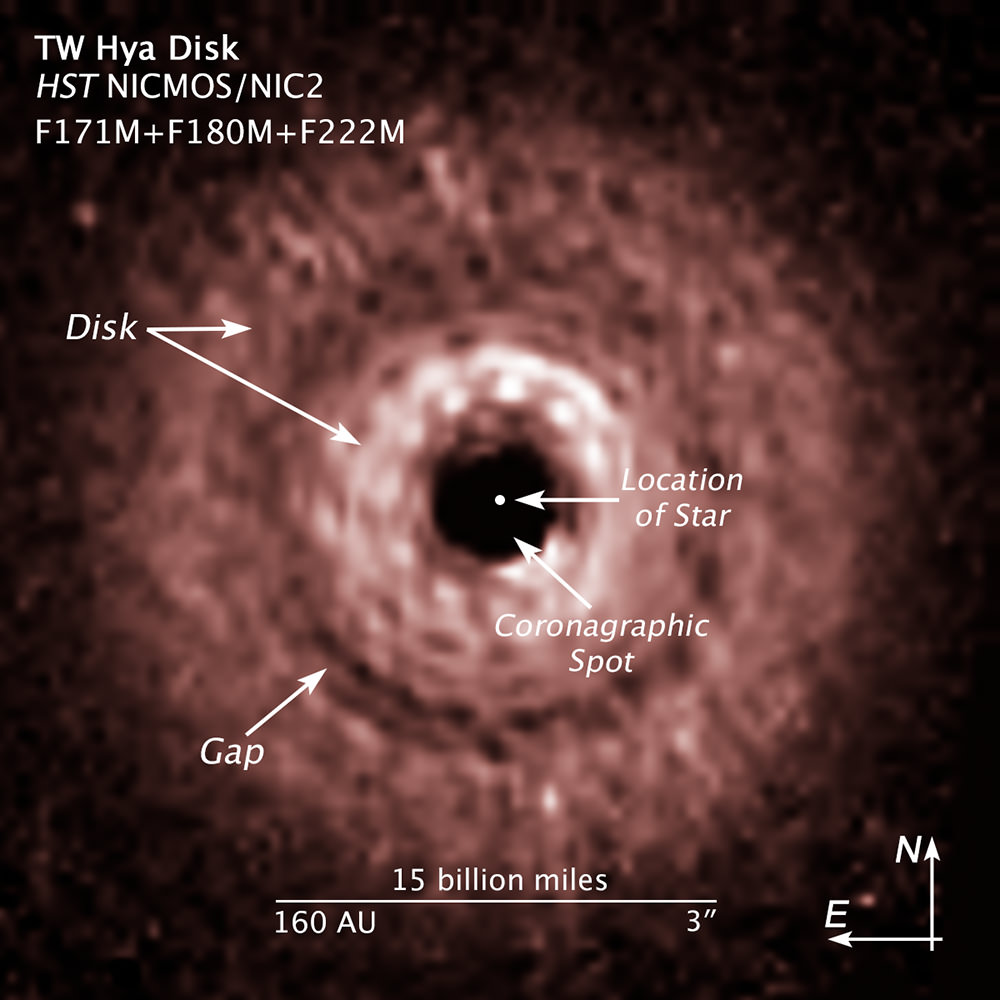

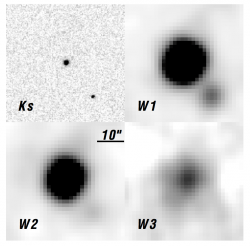

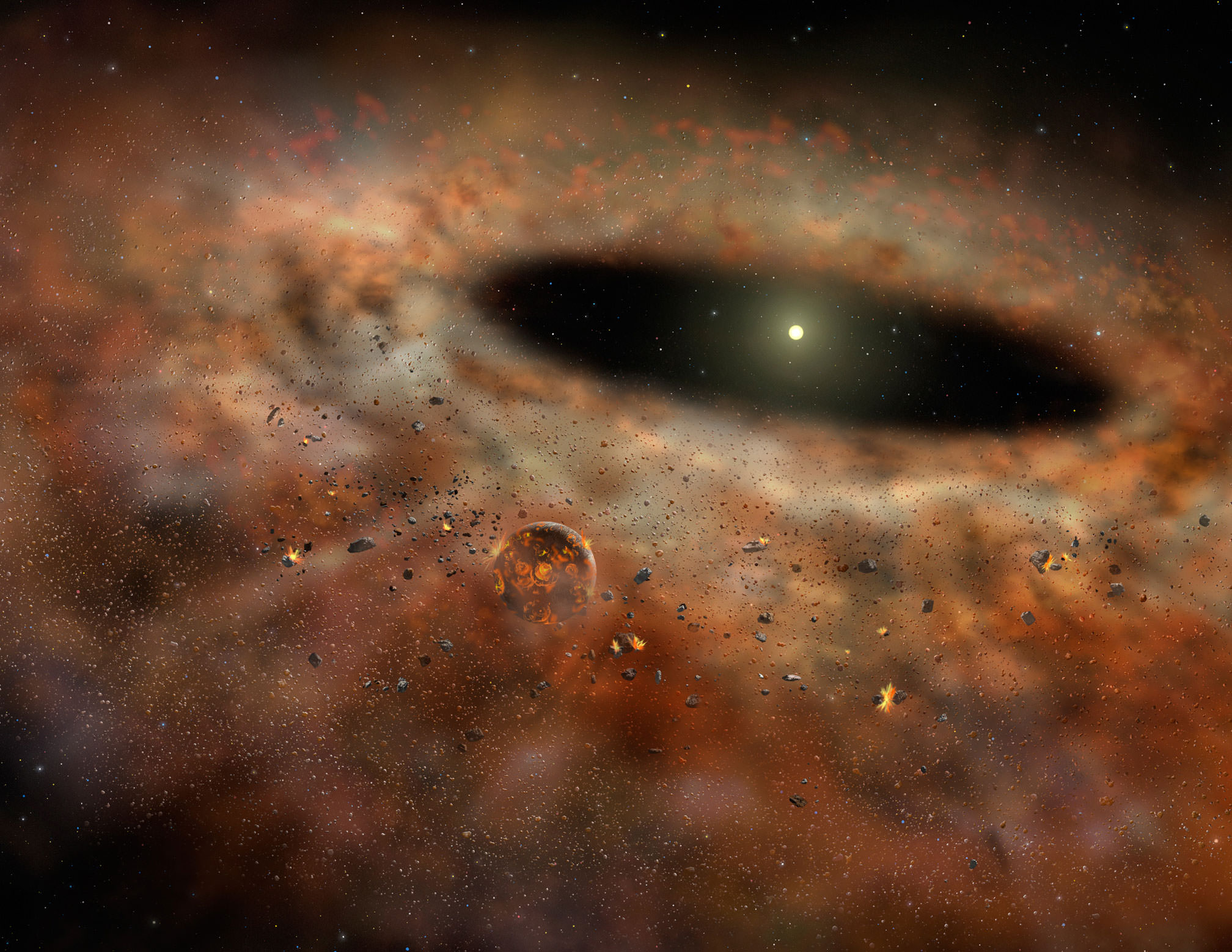

Take a close look at the blurry image above. See that gap in the cloud? That could be a planet being born some 176 light-years away from Earth. It’s a small planet, only 6 to 28 times Earth’s mass.

That’s not even the best part.

This alien world, if we can confirm it, shouldn’t be there according to conventional planet-forming theory.

The gap in the image above — taken by the Hubble Space Telescope — probably arose when a planet under construction swept through the dust and debris in its orbit, astronomers said.

That’s not much of a surprise (at first blush) given what we think we know about planet formation. You start with a cloud of debris and gas swirling around a star, then gradually the bits and pieces start colliding, sticking together and growing bigger into small rocks, bigger ones and eventually, planets or gas giant planet cores.

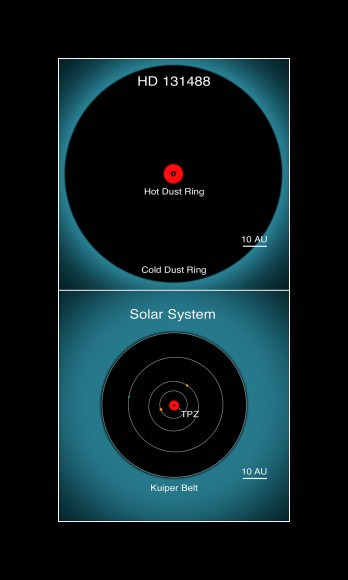

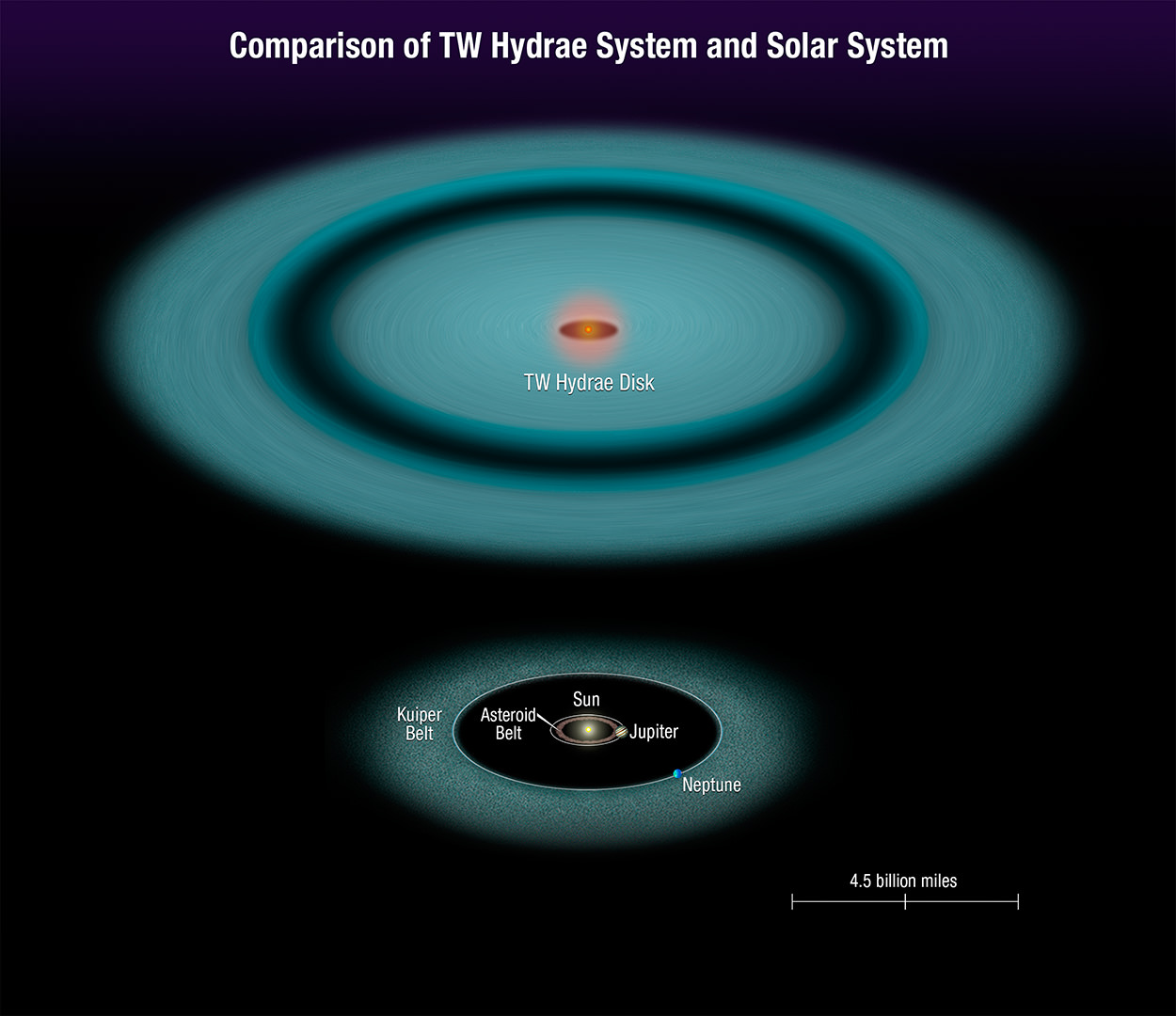

But there’s something puzzling astronomers this time around: this planet is a heck of a long way from its star, TW Hydrae, about twice Pluto’s distance from the sun. Given that alien systems’ age, that world shouldn’t have formed so quickly.

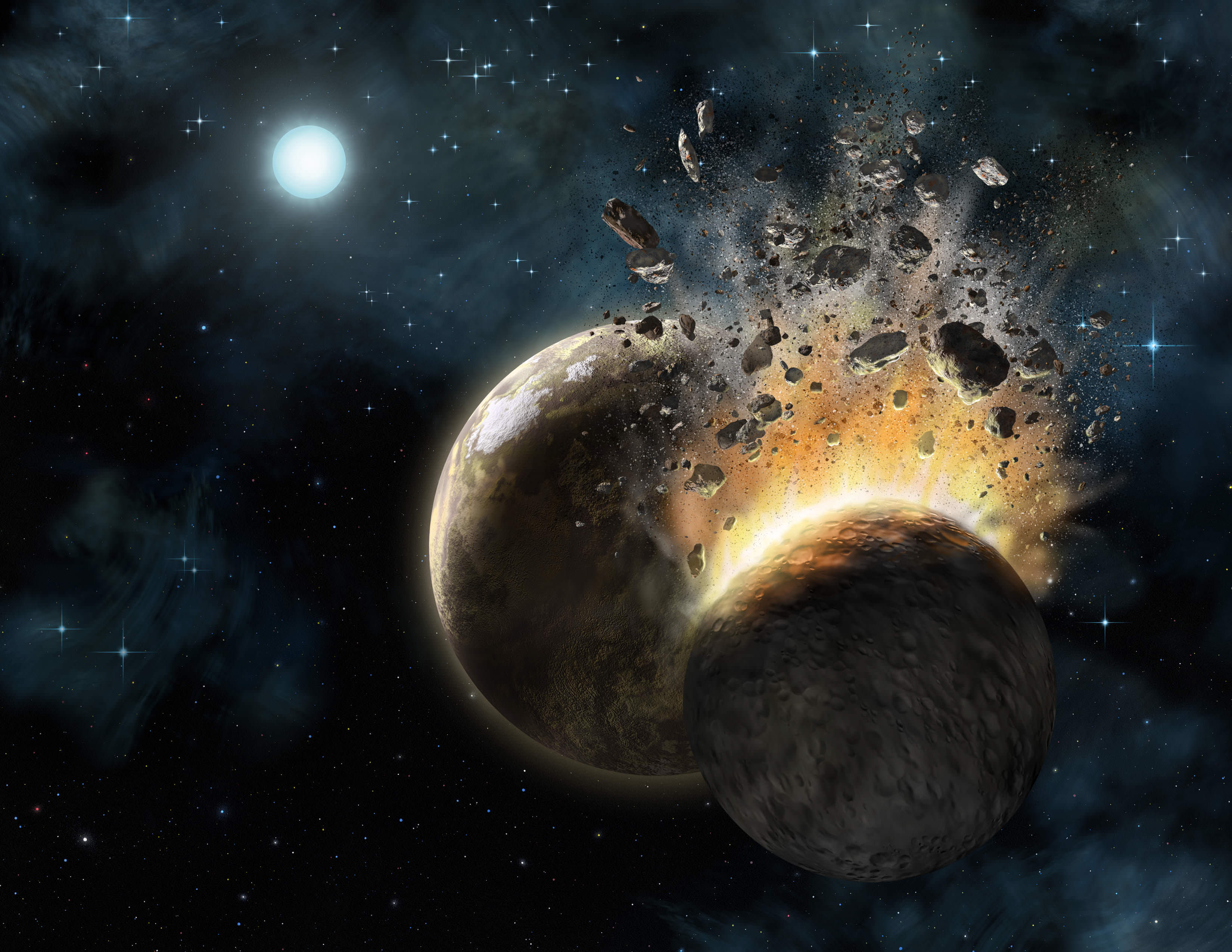

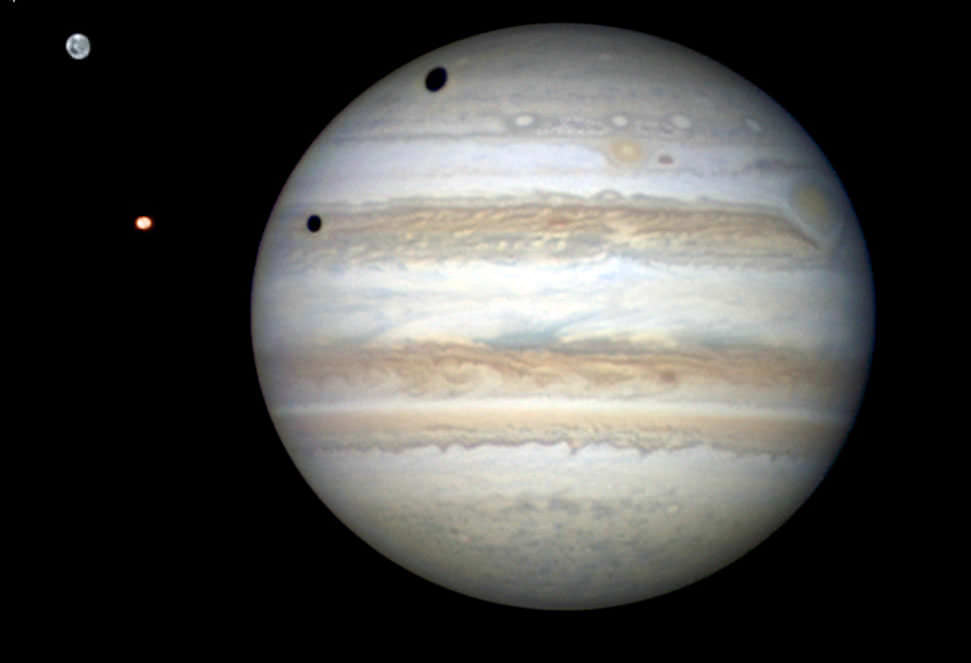

Astronomers believe that Jupiter took about 10 million years to form at its distance away from the sun. This planet near TW Hydrae should take 200 times longer to form because the alien world is moving slower, and has less debris to pick up.

But something must be off, because TW Hydrae‘s system is believed to be only 8 million years old.

“There has not been enough time for a planet to grow through the slow accumulation of smaller debris. Complicating the story further is that TW Hydrae is only 55 percent as massive as our sun,” NASA stated, adding it’s the first time we’ve seen a gap so far away from a low-mass star.

The lead researcher put it even more bluntly: “Typically, you need pebbles before you can have a planet. So, if there is a planet and there is no dust larger than a grain of sand farther out, that would be a huge challenge to traditional planet formation models,” stated John Debes, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore.

At this point, you would suppose the astronomers are seriously investigating other theories. One alternative brought up in the press release: perhaps part of the disc collapsed due to gravitational instability. If that is the case, a planet could come to be in only a few thousand years, instead of several million.

“If we can actually confirm that there’s a planet there, we can connect its characteristics to measurements of the gap properties,” Debes stated. “That might add to planet formation theories as to how you can actually form a planet very far out.”

There’s a trick with the “direct collapse” theory, though: astronomers believe it takes a bunch of matter that is one to two times more massive than Jupiter before a collapse can occur to form a planet.

Recall that this world is no more than 28 times the mass of Earth, as best as we can figure. Well, Jupiter itself is 318 times more massive than Earth.

There are also intriguing results about the gap. Chile’s Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) — which is designed to look at dusty regions around young stars — found that the dust grains in this system, orbiting nearby the gap, are still smaller than the size of a grain of sand.

Astronomers plan to use ALMA and the James Webb Space Telescope, which should launch in 2018, to get a better look. In the meantime, the results will be published in the June 14 edition of the Astrophysical Journal.

Source: HubbleSite