China’s Tiangong-1 space station has been the focus of a lot of international attention lately. In 2016, after four and half years in orbit, this prototype space station officially ended its mission. By September of 2017, the Agency acknowledged that the station’s orbit was decaying and that it would fall to Earth later in the year. Since then, estimates on when it will enter out atmosphere have been extended a few times.

According to satellite trackers, it was predicted that the station would fall to Earth in mid-March. But in a recent statement (which is no joke) the Chinese National Space Agency (CNSA) has indicated that Tiangong-1 will fall to Earth around April 1st – aka. April Fool’s Day. While the agency and others insists that it is very unlikely, there is a small chance that the re-entry could lead to some debris falling to Earth.

For the sake of ensuring public safety, the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Space Debris Office (SDO) has been providing regular updates on the station’s decay. According to the SDO, the reentry window is highly variable and spans from the morning of March 31st to the afternoon of April 1st (in UTC time). This works out to the evening of March 30th or March 31st for people living on the West Coast.

As the ESA stated on their rocket science blog:

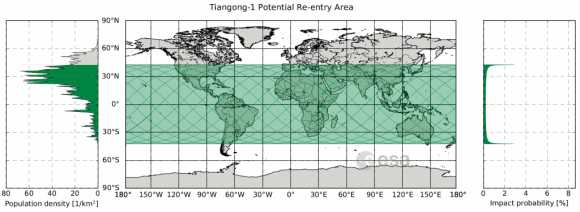

“Reentry will take place anywhere between 43ºN and 43ºS. Areas above or below these latitudes can be excluded. At no time will a precise time/location prediction from ESA be possible. This forecast was updated approximately weekly through to mid-March, and is now being updated every 1~2 days.”

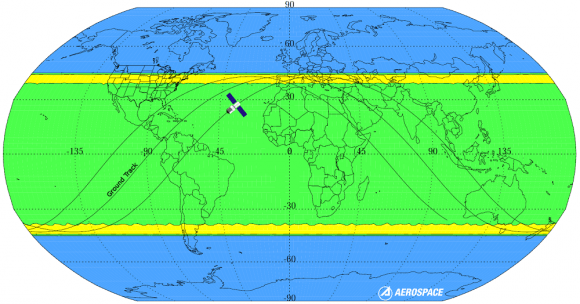

In other words, if any debris does fall to the surface, it could happen anywhere from the Northern US, Southern Europe, Central Asia or China to the tip of Argentina/Chile, South Africa, or Australia. Basically, it could land just about anywhere on the planet. On the other hand, back in January, the US-based Aerospace Corporation released a comprehensive analysis on Tiangong-1s orbital decay.

Their analysis included a map (shown below) which illustrated the zones of highest risk. Whereas the blue areas (that make up one-third of the Earth’s surface) indicate zones of zero probability, the green area indicates a zone of lower probability. The yellow areas, meanwhile, indicates zones that have a higher probability, which extend a few degrees south of 42.7° N and north of 42.7° S latitude, respectively.

The Aerospace Corporation has also created a dashboard for tracking Tiangong-1 (which is refreshed every few minutes) and has come to similar conclusions about the station’s orbital decay. Their latest prediction is that the station will descend into our atmosphere on April 1st, at 04:35 UTC (March 30th 08:35 PST), with a margin of error of about 24 hours – in other words, between March 30th to April 2nd.

And they are hardly alone when it comes to monitoring Tiangong-1’s orbit and predicting its descent. The China Human Spaceflight Agency (CMSA) recently began providing daily updates on the orbital status of Tiangong-1. As they reported on March 28th: “Tiangong-1 stayed at an average altitude of about 202.3 km. The estimated reentry window is between 31 March and 2 April, Beijing time.”

The US Space Surveillance Network, which is responsible for tracking artificial objects in Earth’s orbit, has also been monitoring Tiangong-1 and providing daily updates. Based on their latest tracking data, they estimate that the station will enter our atmosphere no later than midnight on April 3rd.

Naturally, one cannot help but notice that these predictions vary and are subject to a margin of error. In addition, trackers cannot say with any accuracy where debris – if any – will land on the planet. As Max Fagin – an aerospace engineer and space camp alumni – explained in a recent Youtube video (posted below), all of this arises from two factors: the station’s flight path and the Earth’s atmosphere.

Basically, the station is still moving at a velocity of 7.8 km/sec (4.8 mi/s) horizontally while it is descending by about 3 cm/sec. In addition, the Earth’s atmosphere shrinks and expands throughout the day in response to the Sun’s heating, which results in changes in air resistance. This makes the process of knowing where the station’s will make its descent difficult to predict, not to mention where debris could fall.

However, as Fagin goes on to explain, once the station reaches an altitude of 150 km (93 mi) – i.e. within the Thermosphere – it will begin falling much faster. At that point, it be much easier to determine where debris (if any) will fall. However, as the ESA, CNSA, and other trackers have emphasized repeatedly, the odds of any debris making it to the surface is highly unlikely.

If any debris does survive re-entry, it is also statistically likely to fall into the ocean or in a remote area – far away from any population centers. But in all likelihood, the station will break up completely in our atmosphere and produce a beautiful streaking effect across the sky. So if you’re checking the updates regularly and are in a part of the world where it can be seen, be sure to get outside and see it!

Further Reading: GB Times