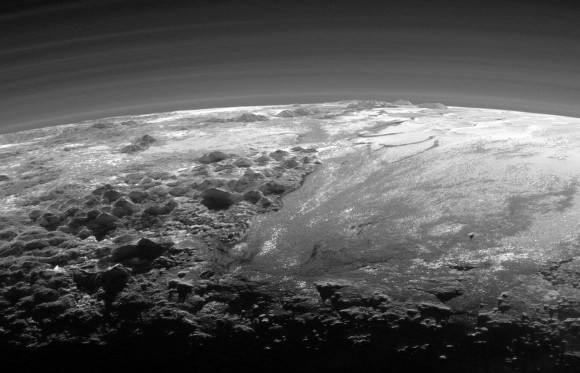

It was two years ago this morning that we awoke to see the now iconic image of Pluto that the New Horizons spacecraft had sent to Earth during the night. You, of course, know the picture I’m talking about – the one with a clear view of the giant heart-shaped region on the distant, little world (see above).

This image was taken just 16 hours before the spacecraft would make its closest approach to Pluto. Then, during that seemingly brief flyby (after traveling nine-and-a-half years and 3 billion miles to get there), the spacecraft gathered as much data as possible and we’ve been swooning over the images and pondering the findings from New Horizons ever since.

“This is what we came for – these images, spectra and other data types that are helping us understand the origin and the evolution of the Pluto system for the first time,” New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern told me last year. “We’re seeing that Pluto is a scientific wonderland. The images have been just magical. It’s breathtaking.”

See a stunning new video created from flbyby footage in honor of the two-year anniversary of the flyby:

All the images have shown us that Pluto is a complex world with incredible diversity, in its geology and also in its atmosphere.

While the iconic “heart” image shows a clear and cloudless view of Pluto, a later image showed incredible detail of Pluto’s hazy atmosphere, with over two dozen concentric layers that stretches more than 200 km high in Pluto’s sky.

With all those layers and all that haze, could there be clouds on Pluto too?

This is a question Stern and his fellow scientists have been asking for a long time, actually, as they have been studying Pluto for decades from afar. Now with data from New Horizons, they’ve been able to look closer. While Stern and his colleagues have been discussing how they found possible clouds on Pluto for a few months, they have now detailed their findings in a paper published last month.

“Numerous planets in our solar system, including Venus, Earth, Mars, Titan, and all four of the giant planets possess atmospheres that contain clouds, i.e., discrete atmospheric condensation structures,” the team wrote in their paper. “This said, it has long been known that Pluto’s current atmosphere is not extensively cloudy at optical or infrared wavelengths.”

They explained that evidence for this came primarily from the “high amplitude and temporal stability of Pluto’s lightcurve,” however, because no high spatial resolution imagery of Pluto was possible before New Horizons, it remained to be seen if clouds occur over a small fraction of Pluto’s surface area.

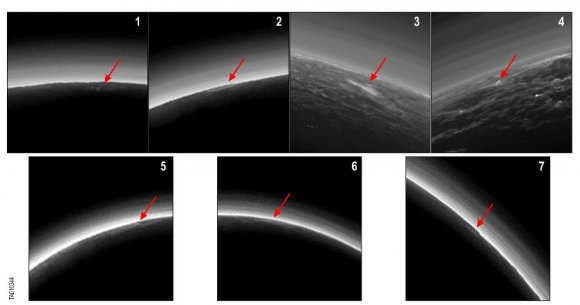

But now with flyby images in hand, the team set out to do searches for clouds on Pluto, looking at all available imagery from the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager and the Multispectral Visible Imaging Camera, looking at both the disk of Pluto and near and on the limb. Since an automated cloud search was nearly impossible, it was all done by visual inspection of the images by the scientists.

They looked for features in the atmosphere that including brightness, fuzzy or fluffy-looking edges and isolated borders.

6, 7) were taken by LORRI. Arrows indicate each PCC. Credit: Stern et al, 2017.

In all, they found seven bright, discrete possible cloud candidates. The seven candidates share several different attributes including small size, low altitude, they all were visible either early or late in the day local time, and were only visible at oblique geometry – which is basically a sideways look from the spacecraft.

Also, several cloud candidates also coincided with brighter surface features below, so the team is still pondering the correlation.

“The seven candidates are all similar in that they are very low altitude,” Stern said last fall at the Division of Planetary Sciences meeting, “and they are all low-lying, isolated small features, so no broad cloud decks or fields. When we map them over the surface, they all lie near the terminator, so they occur near dawn or dusk. This is all suggestive they are clouds because low-lying regions and dawn or dusk provide cooler conditions where clouds may occur.”

While haze was detected as high as 220 km, the possible clouds were found at very low altitudes. Stern told Universe Today that these possible, rare condensation clouds could be made of ethane, acetylene, hydrogen cyanide or methane under the right conditions. Stern added these clouds are probably short-lived phenomena – again, likely occurring only at dawn or dusk. A day on Pluto is 6.4 days on Earth.

But all in all, they concluded that at the current time Pluto’s atmosphere is almost entirely free of clouds – in fact the dwarf planet’s sky was 99% cloud free the day that New Horizons whizzed by.

“But if there are clouds, it would mean the weather on Pluto is even more complex than we imagined,” Stern said last year.

The seven cloud candidates cannot be confirmed as clouds because none are in the region where there was stereo imaging or other available ways to cross-check it. They concluded that further modeling would be needed, but specifically a Pluto orbiter mission would be the only way to “search for clouds more thoroughly than time and space and was possible during the brief reconnaissance flyby by New Horizons.”

If you’re dreaming of a Pluto orbiter, you can read about some possibilities of how to do it in our article from May of this year.