[/caption]

On December 25, 2010, at 1:38 p.m. EST, NASA’s Swift Burst Alert Telescope detected a particularly long-lived gamma-ray burst in the constellation Andromeda. Lasting nearly half an hour, the burst (known as GRB 101225A) originated from an unknown distance, leaving astronomers to puzzle over exactly what may have created such a dazzling holiday display.

Now there’s not just one but two theories as to what caused this burst, both reported in papers by a research team from the Institute of Astrophysics in Granada, Spain. The papers will appear in the Dec. 1 issue of Nature.

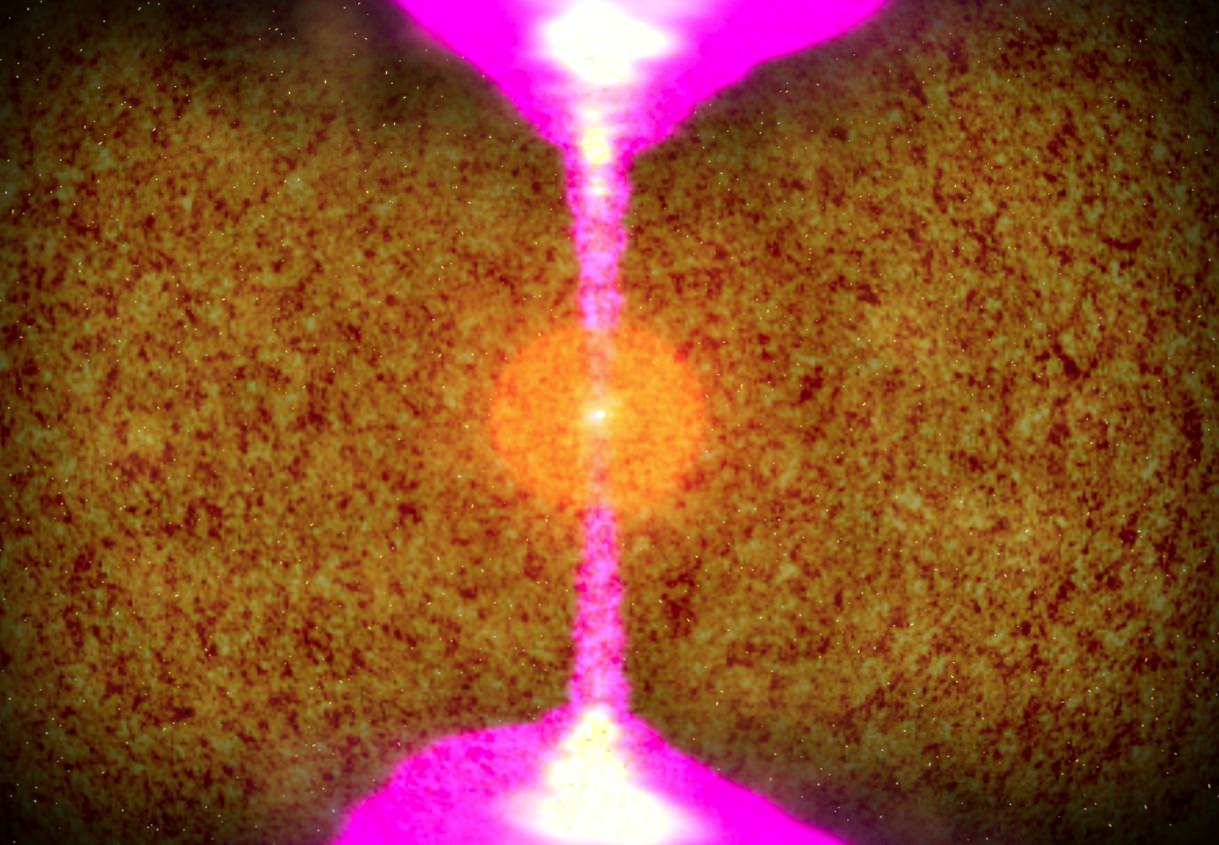

Gamma-ray bursts are the Universe’s most luminous explosions. Most occur when a massive star runs out of nuclear fuel. As the star’s core collapses, it creates a black hole or neutron star that sends intense jets of gas and radiation outwards. As the jets shoot into space they strike gas previously shed by the star and heat it, generating bright afterglows.

If a GRB jet happens to be aimed towards Earth it can be detected by instruments like those aboard the Swift spacecraft.

Luckily GRBs usually come from vast distances, as they are extremely powerful and could potentially pose a danger to life on Earth should one strike directly from close enough range. Fortunately for us the odds of that happening are extremely slim… but not nonexistent. That is one reason why GRBs are of such interest to astronomers… gazing out into the Universe is, in one way, like looking down the barrels of an unknown number of distant guns.

The 2010 “Christmas burst”, as the event also called, is suspected to feature a neutron star as a key player. The incredibly dense cores that are left over after a massive star’s death, neutron stars rotate extremely rapidly and have intense magnetic fields.

One of the new theories envisions a neutron star as part of a binary system that also includes an expanding red giant. The neutron star may have potentially been engulfed by the outer atmosphere of its partner. The gravity of the neutron star would have caused it to acquire more mass and thus more momentum, making it spin faster while energizing its magnetic field. The stronger field would have then fired off some of the stellar material into space as polar jets… jets that then interacted with previously-expelled gases, creating the GRB detected by Swift.

This scenario puts the source of the Christmas burst at around 5.5 billion light-years away, which coincides with the observed location of a faint galaxy.

An alternate theory, also accepted by the research team, involves the collision of a comet-like object and a neutron star located within our own galaxy, about 10,000 light-years away. The comet-like body could have been something akin to a Kuiper Belt Object which, if in a distant orbit around a neutron star, may have survived the initial supernova blast only to end up on a spiraling path inwards.

The object, estimated to be about half the size of the asteroid Ceres, would have broken up due to tidal forces as it neared the neutron star. Debris that impacted the star would have created gamma-ray emission detectable by Swift, with later-arriving material extending the duration of the GRB into the X-ray spectrum… also coinciding with Swift’s measurements.

Both of these scenarios are in line with processes now accepted by researchers as plausible explanations for GRBs thanks to the wealth of data provided by the Swift telescope, launched in 2004.

“The beauty of the Christmas burst is that we must invoke two exotic scenarios to explain it, but such rare oddballs will help us advance the field,” said Chryssa Kouveliotou, a co-author of the study at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

More observations using other instruments, such as the Hubble Space Telescope, will be needed to discern which of the two theories is most likely the case… or perhaps rule out both, which would mean something else entirely is the source of the 2010 Christmas burst!

Read more on the NASA mission site here.