Expedition 34/35: Canadian Space Agency Flight Engineer Chris Hadfield, Soyuz Commander Roman Romanenko and Flight Engineer Tom Marshburn of NASA. The crew launches on Dec. 19, 2012 at 12:12 UTC (7:12 a.m. EST). For the second half of the mission, Hadfield will become the first Canadian commander of the International Space Station. Credit: NASA

Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield has been sharing with us how much there is to learn and the training necessary for living on the International Space Station for five months. But astronauts and cosmonauts also have to learn how to fly on the Russian Soyuz, too, as right now, there’s no other ride to the space station.

“Soyuz is a wonderful spaceship,” Hadfield told Universe Today. “It has been refined and honed and perfected for decades, as if they took an early sculpture of something and have continuously whittled away at it to make it more and more purpose-built and improved.”

A view of Hadfield inside the Soyuz simulator. Credit: NASA

The most modern version, the TMA-M, is as good as they’ve ever made it, Hadfield said, with great modifications and improvements in avionics, sensors, computing power.

“So, it is a very capable, well-designed vehicle; a tough vehicle,” he said. “That is heartening and reassuring. It has the full ability to do almost everything on its own, but also full ability for us to take over and do almost everything manually if we need to.”

“There is an unbelievable thrill in getting into your own spaceship. This is the same hatch we’ll use on the launch pad,” Hadfield said via Twitter.

It is so robust that with just a stopwatch, the crews can bring it safely back to Earth and land within a 10-km circle of where they want to touch down.

All the training is in Russian. “Russian digital motion control theory is complex,” Hadfield said. “It took a full year of intensive one-on-one study to become ready to start flying the Soyuz.” This video shows Hadfield working in the simulator:

Hadfield said that not only does he have great respect for the Soyuz, but for the training provided by the Russian Space Agency, Roscosmos.

“They simulate it well, and they load us up to our limit of what they teach us,” he said, “getting into the very esoteric and complex things that can happen.”

For example, in full-up simulations where the crew are in the pressure suits, the trainers will do things like fill the cockpit with smoke as if there was a fire on board, so the “dashboard” can’t be seen, and the crew needs to know how to keep flying.

“Centrifuges make you dizzy while they accelerate & decelerate, & REALLY mess you up when you move your head. Otherwise OK,” Hadfield Tweeted.

In this video, Hadfield explains the Soyuz centrifuge, the largest human-rated centrifuge in the world, that puts the astronauts and cosmonauts in the same environment – G-force-wise – that they will be in during the harrowing descent when they return home, plummeting through Earth’s atmosphere and experience 4-8 times the force of Earth’s gravity.

“You need to be able to understand how that feels on your body and whether you are going to be able to work in that environment,” Hadfield said.

“Hatch to Another World – what it looks like to climb into a Soyuz spaceship. We then crawl down into our seats,” Hadfield said, via Twitter.

The Soyuz rocket is just as robust and one of the most reliable rockets ever. “The Soyuz launches all-weather, -40 degrees to +40 degrees,” Hadfield said. “It is rugged, built on experience, it is not delicate. I trust it with my life.”

“It takes these 32 engines to get these 3 humans safely above the air. And that’s just the start,” Hadfield said via Twitter.

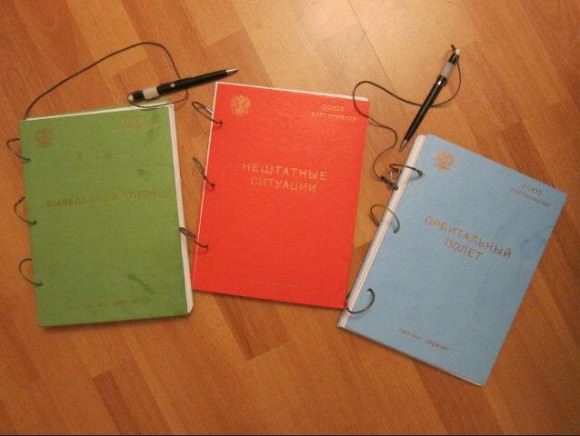

“My Soyuz Checklists – from L to R: Launch/Entry, Malfunctions, Orbital Flight. Colour-coded for easy spaceflight,” said Hadfield via Twitter.

Hadfield talks about the Russian technology for the rocket and spaceship he will be flying in:

Hadfield’s son and daughter-in-law gave him a Soyuz-like pre-flight Christmas present:

“My first Soyuz simulator! Summer 1964, nearly 5 years old. Never too early to start training,” Hadfield shared on Twitter.

Previous articles in this series:

How to Train for Long Duration Space Flight with Chris Hadfield

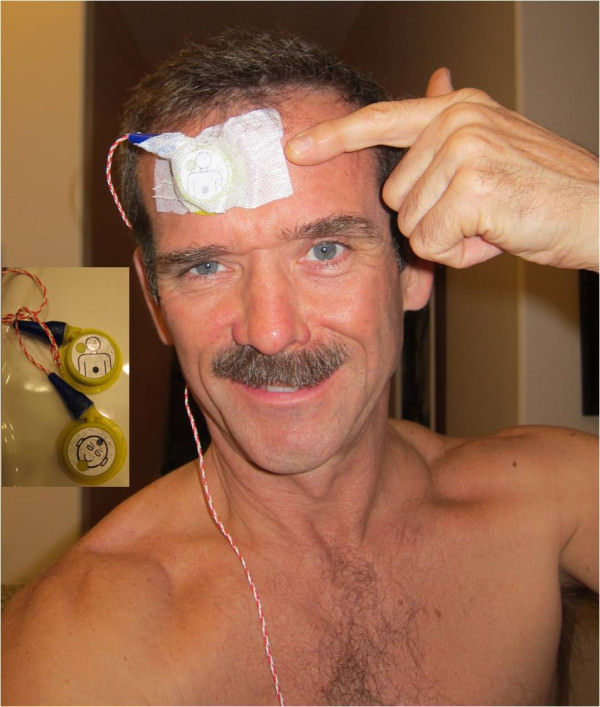

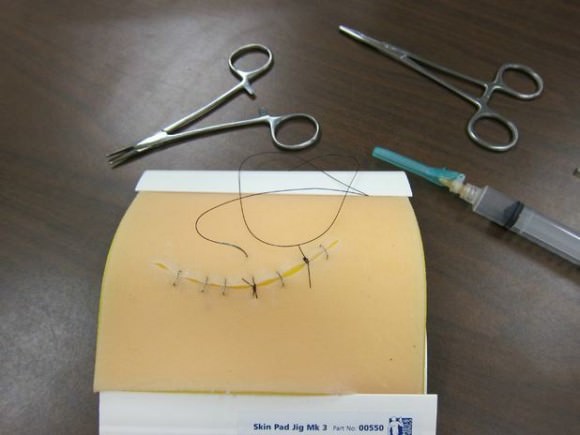

How to Train for a Mission to the ISS: Medical Mayhem

How to Train for a Mission to the ISS: Eating in Space