The Moon is great and all, but I wish it was closer. Close enough that I could see all kinds of detail on its surface without a telescope or a pair of binoculars. Close enough that I could just reach up and grab enough cheese for a lifetime of grilled cheese sandwiches.

Sure, there would be all kinds of horrible problems with having the Moon that much closer. Intense tides, a total lack of good dark nights for stargazing, and something else… Oh right, the total destruction of life on Earth. On second thought the Moon can stay right where it is, thank you very much.

The Earth’s Moon is located an average distance of 384,400 kilometers away. I say average because the Moon actually follows an elliptical orbit. At its closest point, it’s only 362,600 km, and at its furthest point, it’s 405,400 kilometers.

Still, that’s so far that it takes light a little over a second to reach the Moon, traveling almost 300,000 km/s. The Moon is far.

But what if the Moon was much closer? How close could it get and still be the Moon?

Once again, I need to remind you that this is purely theoretical. The Moon isn’t getting closer to us, in fact, it’s getting further. The Moon is slowly drifting away from us at a distance of almost 4 centimeters per year.

Let’s go back to the beginning, when the young Earth collided with a Mars-sized planet billions of years ago. This catastrophic encounter completely resurfaced planet Earth, and kicked up a massive amount of debris into orbit. Well, a Moon’s worth of debris, which collected together by mutual gravity into the roughly spherical Moon we recognize today.

Shortly after its formation, the Moon was much closer, and the Earth was spinning more rapidly. A day on Earth was only 6 hours long, and the Moon took just 17 days to orbit the Earth.

The Earth’s gravity stopped the Moon’s relative rotation, and the Moon’s gravity has been slowing the Earth’s rotation. To maintain the overall angular momentum of the system, the Moon has been drifting away to compensate.

This conservation of momentum is very important because it works both ways. As long as a moon takes longer than a day to orbit its planet, you’re going to see this same effect. The planet’s rotation slows, and the moon drifts further to compensate.

But if you have a scenario where the moon orbits faster than the planet rotates, you have the exact opposite situation. The moon makes the planet rotate more quickly, and it drifts closer to compensate. This can’t end well.

Once you get close enough, gravity becomes a harsh mistress.

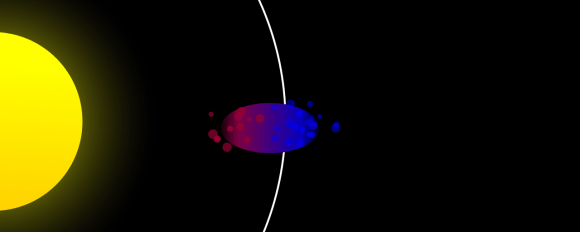

There’s a point in all gravitational interactions called the Roche Limit. This is the point at which an object held together by gravity (like the Moon), gets close enough to another celestial body that it gets torn apart.

The exact point depends on the mass, size and density of the two objects. For example, the Roche Limit between the Earth and the Moon is about 9,500 kilometers, assuming the Moon is a solid ball. In other words, if the Moon gets within 9,500 kilometers or so, of the Earth, the gravity of the Earth overwhelms the gravity holding the Moon together.

The Moon would be torn apart, and turned into a ring. And then the pieces of the ring would continue to orbit the Earth until they all came crashing down. When that happened, it would be a series of very bad days for anyone living on Earth.

If an average comet got within about 18,000 km of Earth, it would get torn to pieces. While the Sun can, and does, tear apart comets from about 1.3 million km away.

This sounds purely theoretical, but this is actually going to happen over at Mars. Its largest moon Phobos orbits more quickly than a Martian day, which means that it’s drifting closer and closer to the planet. In a few million years, it’ll cross the Roche Limit, tear into a ring, and then all the pieces of the former Phobos will crash down onto Mars. We did a whole article on this.

Now you might be wondering, wait a second. I’m a separate object from the Earth, why don’t I get torn apart since I’m definitely within the Earth’s Roche Limit.

You do have gravity holding you together, but it’s insignificant compared to the chemical bonds holding you together. This is why physicists consider gravity to actually be a pretty weak force compared to all the other forces of the Universe.

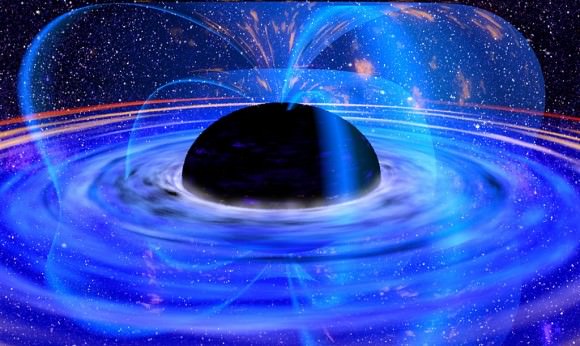

You’d need to go somewhere with really intense gravity, like a black hole, for the Roche Limit to overcome the forces holding you together.

So that’s it. Bring the Moon within 9,500 kilometers or so and it would no longer be a Moon. It would be torn apart into a ring, a Halo ring, if you will, capable of wiping out all life on a planet infected by the flood. All the moons we see in the Solar System are are least at the Roche Limit or beyond, otherwise they would have broken up long ago… and probably did.