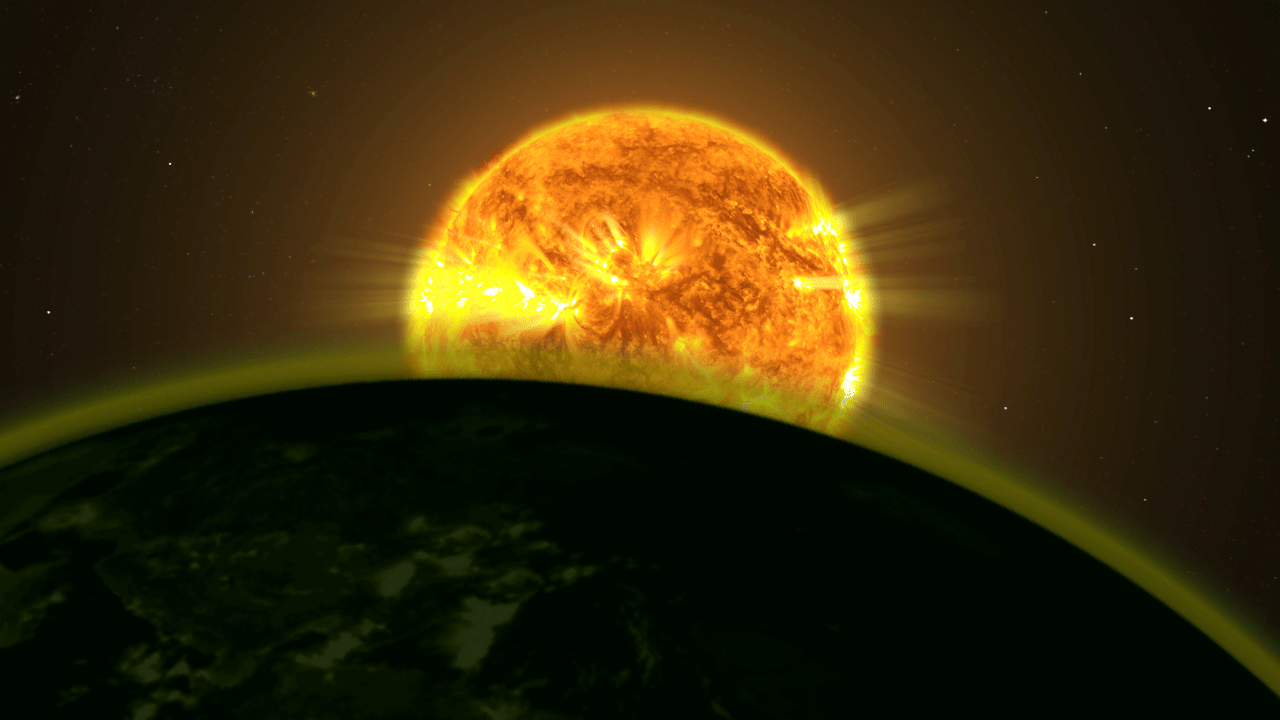

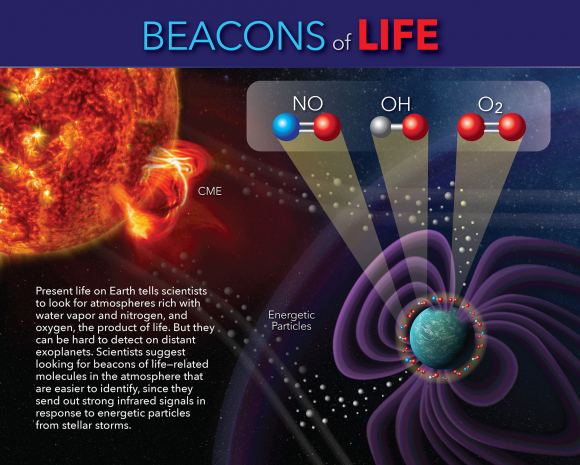

When it comes to looking for life on extra-solar planets, scientists rely on what is known as the “low-hanging fruit” approach. In lieu of being able to observe these planets directly or up close, they are forced to look for “biosignatures” – substances that indicate that life could exist there. Given that Earth is the only planet (that we know of) that can support life, these include carbon, oxygen, nitrogen and water.

However, while the presence of these elements are a good way of gauging “habitability”, they are not necessarily indications that extra-terrestrial civilizations exist. Hence why scientists engaged in the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence (SETI) also keep their eyes peeled for “technosignatures”. Targeting the Kepler field, a team of scientists recently conducted a study that examined 14 planetary systems for indications of intelligent life.

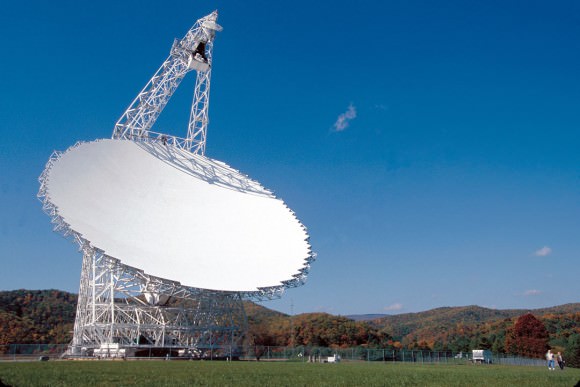

The study, titled “A search for technosignatures from 14 planetary systems in the Kepler field with the Green Bank Telescope at 1.15-1.73 GHz“, recently appeared online and is being reviewed for publication by The Astronomical Journal. The team was led by Jean-Luc Margot, the Chair of the UCLA Department of Earth, Planetary, and Space Sciences (UCLA EPSS) and a Professor with UCLA’s Department of Physics and Astronomy.

In addition to Margot, the team consisted of 15 graduate and undergraduate students from UCLA and a postdoctoral researcher from the Green Bank Observatory and the Center for Gravitational Waves and Cosmology at West Virginia University. All of the UCLA students participated in the 2016 course, “Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence: Theory and Applications“.

Together, the team selected 14 systems from the Kepler catalog and examined them for technosignatures. While radio waves are a common occurrence in the cosmos, not all sources can be easily attributed to natural causes. Where and when this is the case, scientists conduct additional studies to try and rule out the possibility that they are a technosignature. As Professor Margot told Universe Today via email:

“In our article, we define a “technosignature” as any measurable property or effect that provides scientific evidence of past or present technology, by analogy with “biosignatures,” which provide evidence of past or present life.”

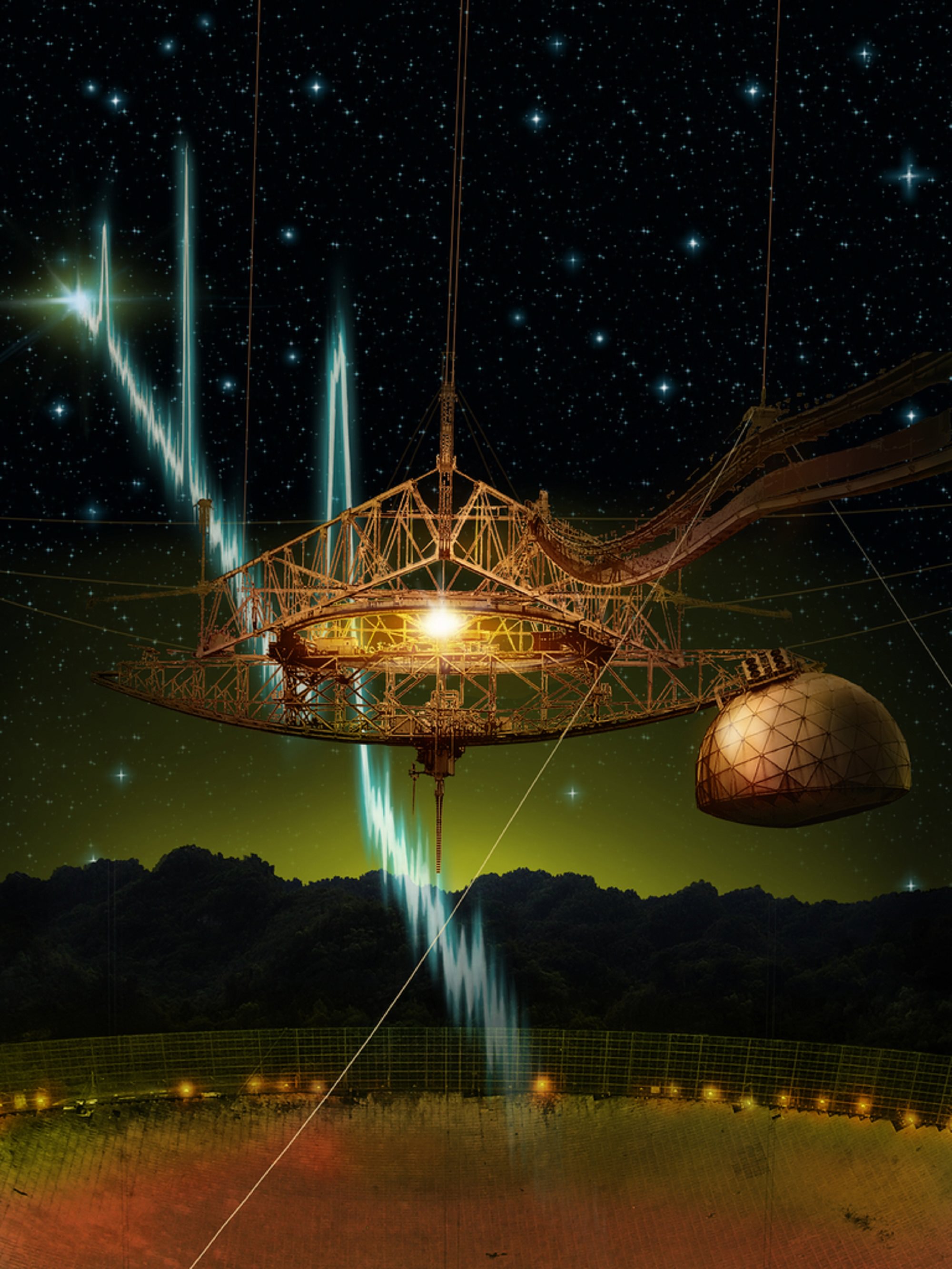

For the sake of their study, the team conducted an L-band radio survey of these 14 planetary systems. Specifically, they looked for signs of radio waves in the 1.15 to 1.73 gigahertz (GHz) range. At those frequencies, their study is sensitive to Arecibo-class transmitters located within 450 light-years of Earth. So if any of these systems have civilizations capable of building radio observatories comparable to Arecibo, the team hoped to find out!

“We searched for signals that are narrow (< 10 Hz) in the frequency domain,” said Margot. “Such signals are technosignatures because natural sources do not emit such narrowband signals… We identified approximately 850,000 candidate signals, of which 19 were of particular interest. Ultimately, none of these signals were attributable to an extraterrestrial source.”

What they found was that of the 850,000 candidate signals, about 99% of them were automatically ruled out because they were quickly determined to be the result of human-generated radio-frequency interference (RFI). Of the remaining candidates, another 99% were also flagged as anthropogenic because their frequencies overlapped with other known sources of RFI – such as GPS systems, satellites, etc.

The 19 candidate signals that remained were heavily scrutinized, but none could be attributed to an extraterrestrial source. This is key when attempting to distinguish potential signs of intelligence from radio signals that come from the only intelligence we know of (i.e. us!) Hence why astronomers have historically been intrigued by strong narrowband signals (like the WOW! Signal, detected in 1977) and the Lorimer Burst detected in 2007.

In these cases, the sources appeared to be coming from the Messier 55 globular cluster and the Large Magellanic Cloud, respectively. The latter was especially fascinating since it was the first time that astronomers had observered what are now known as Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs). Such bursts, especially when they are repeating in nature, are considered to be one of the best candidates in the search for intelligent, technologically-advanced life.

Unfortunately, these sources are still being investigated and scientists cannot attribute them to unnatural causes just yet. And as Professor Margot indicated, this study (which covered only 14 of the many thousand exoplanets discovered by Kepler) is just the tip of the iceberg:

“Our study encompassed only a small fraction of the search volume. For instance, we covered less than five-millionths of the entire sky. We are eager to scale the effort to sample a larger fraction of the search volume. We are currently seeking funds to expand our search.”

Between Kepler‘s first and second mission (K2), a total of 5,118 candidates and 2,538 confirmed exoplanets have been discovered within our galaxy alone. As of February 1st, 2018, a grand total of 3,728 exoplanets have been confirmed in 2,794 systems, with 622 systems having more than one planet. On top of that, a team of researchers from the University of Oklahoma recently made the first detection of extra-galactic planets as well!

It would therefore be no exaggeration to say that the hunt for ETI is still in its infancy, and our efforts are definitely beginning to pick up speed. There is literally a Universe of possibilities out there and to think that there are no other civilizations that are also looking for us seems downright unfathomable. To quote the late and great Carl Sagan: “The Universe is a pretty big place. If it’s just us, seems like an awful waste of space.”

And be sure to check out this video of the 2017 UCLA SETI Group, courtesy of the UCLA EPSS department:

Further Reading: arXiv