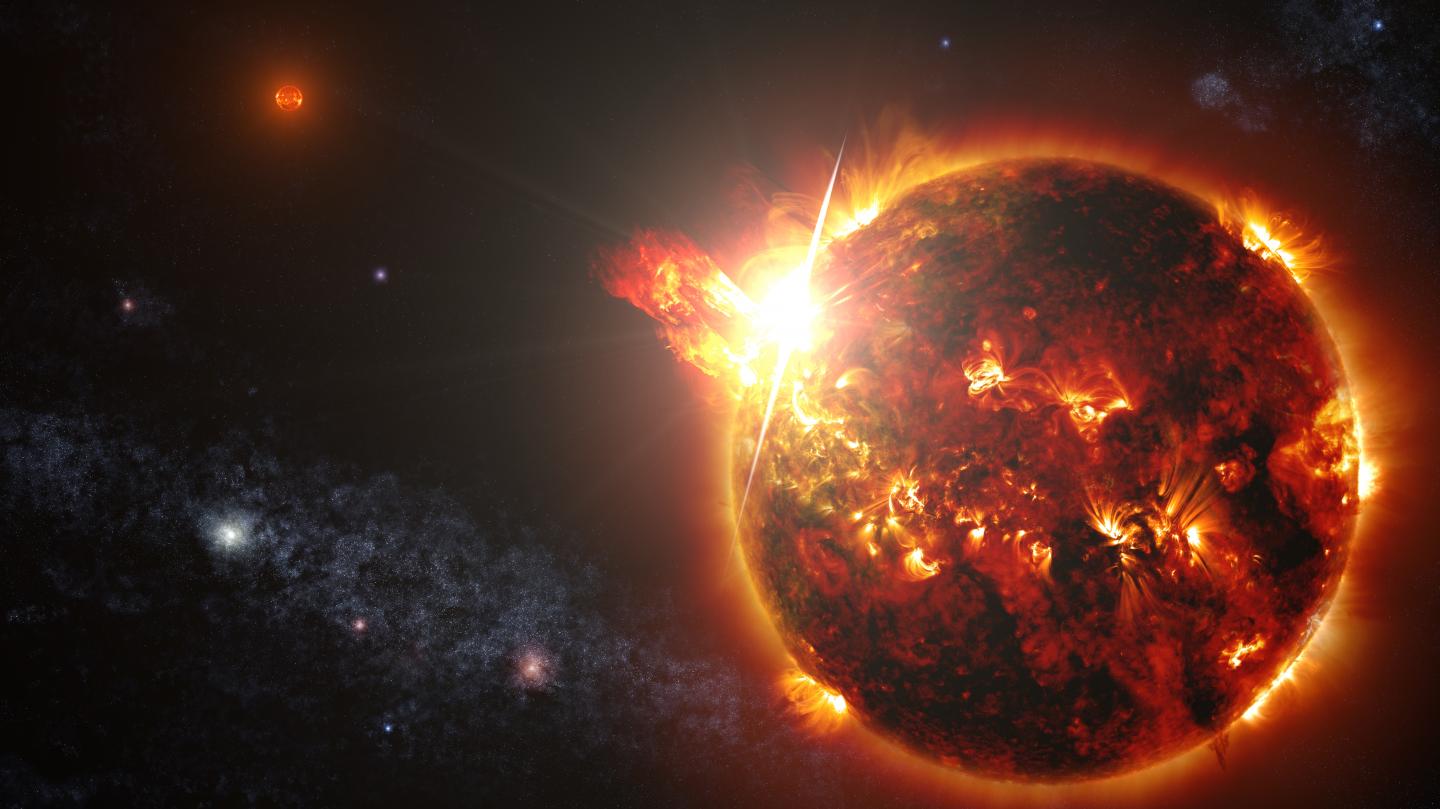

Red dwarf stars, also known as M-dwarfs, dominate the Milky Way’s stellar population. They can last for 100 billion years or longer. Since these long-lived stars make up the bulk of the stars in our galaxy, it stands to reason that they host the most planets.

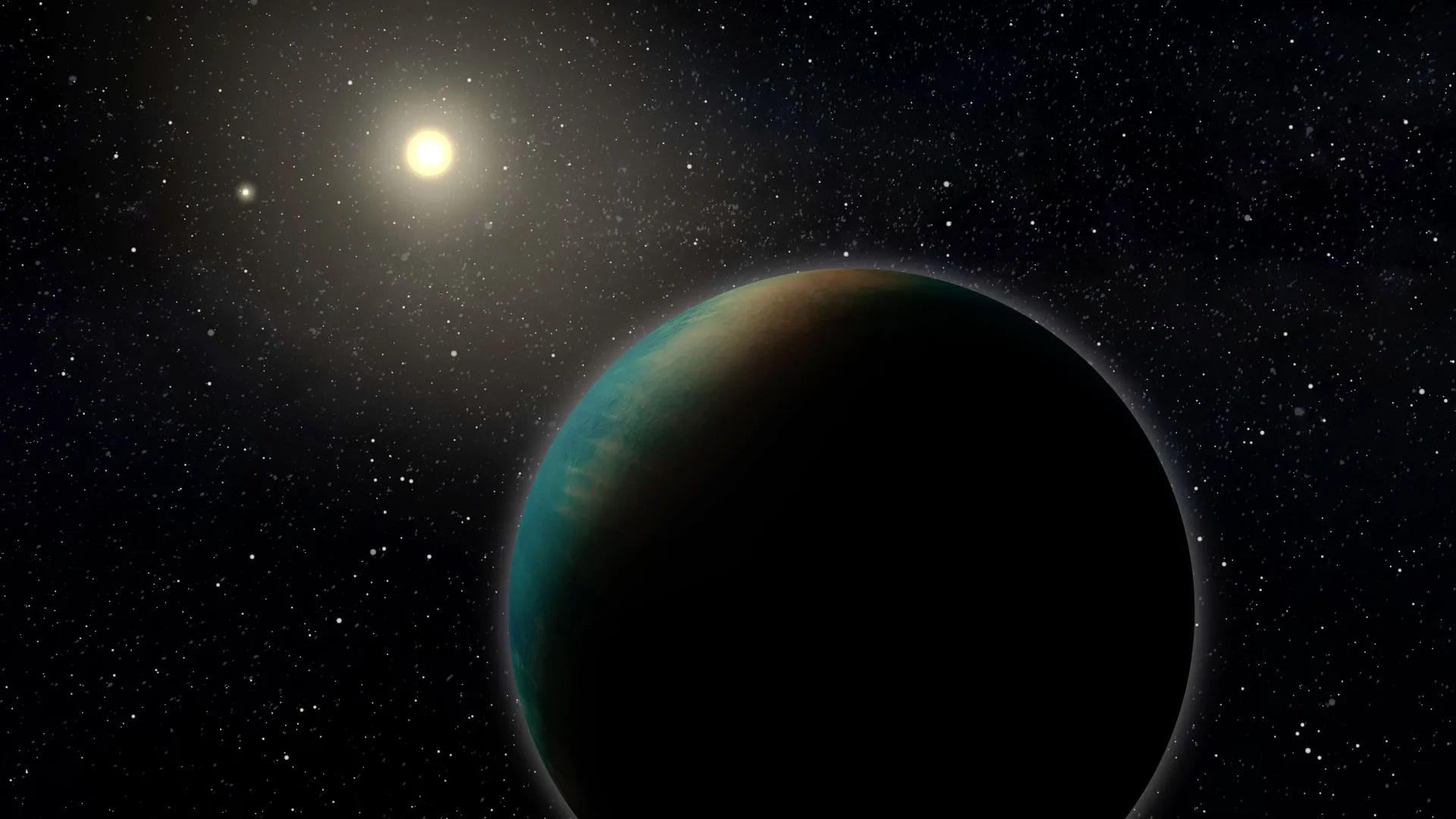

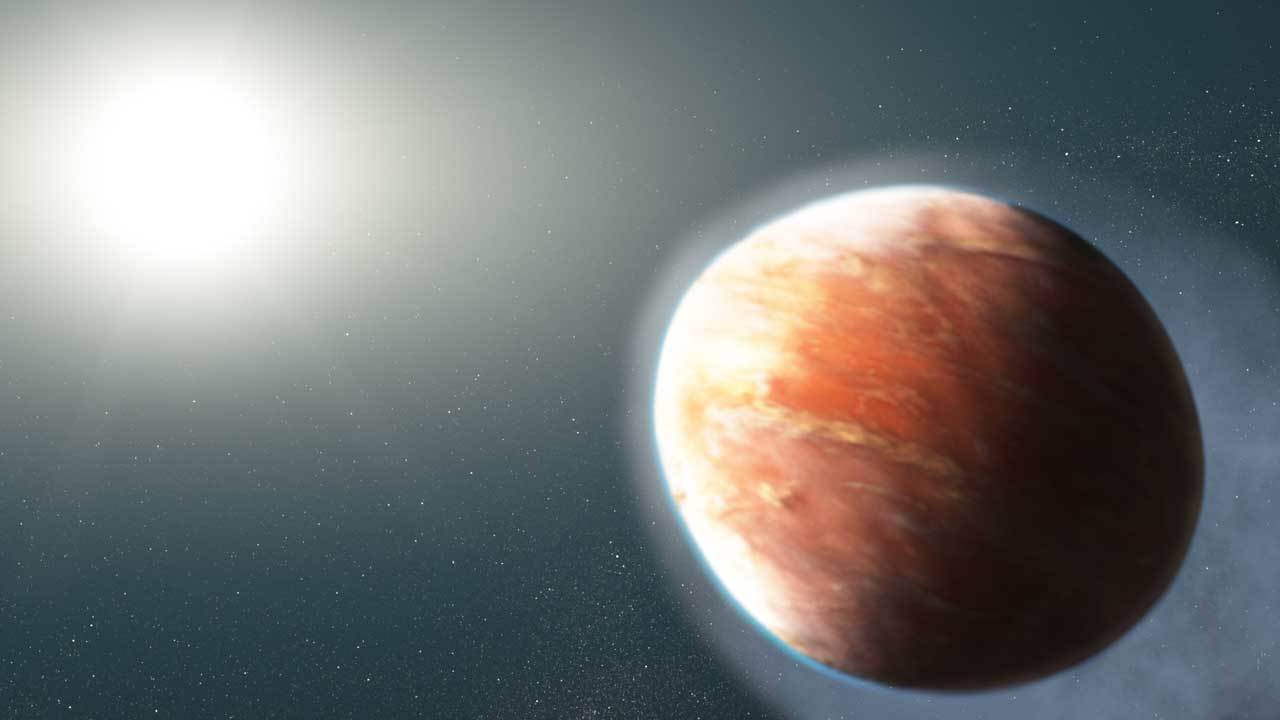

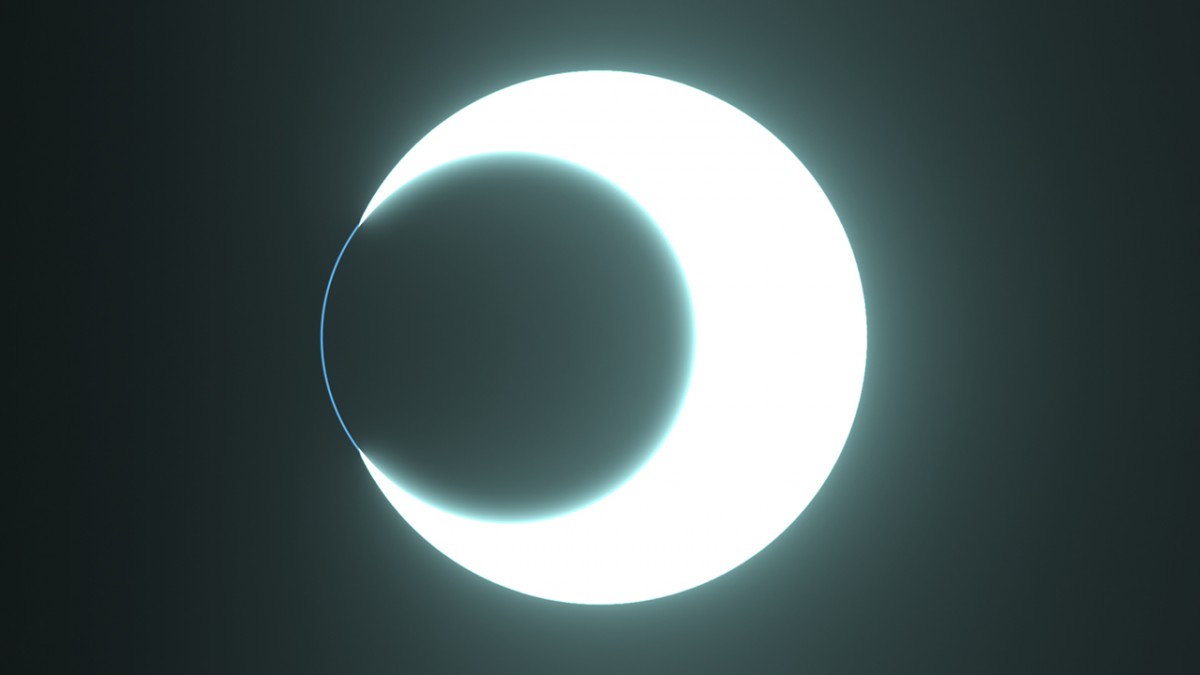

Astronomers examined one red dwarf star named SPECULOOS-3, a Jupiter-sized star about 55 light-years away, and found an Earth-sized exoplanet orbiting it. It’s an excellent candidate for further study with the James Webb Space Telescope.

Continue reading “An Earth-sized Exoplanet Found Orbiting a Jupiter-Sized Star”