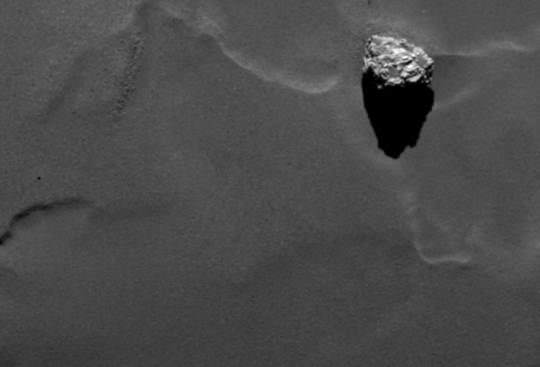

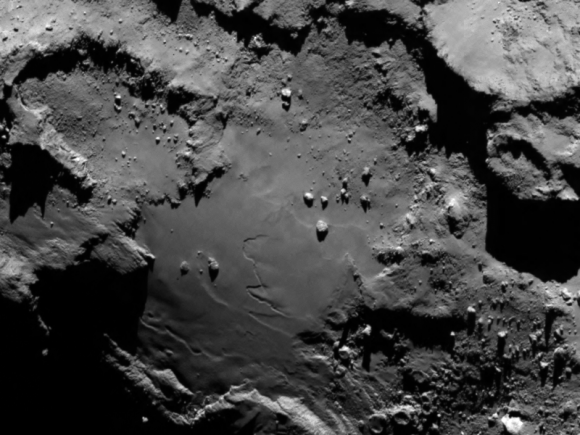

As the Rosetta spacecraft drops a bit closer to its target comet, some really cool features are popping into view. For example, look at this picture of a 150-foot (45-meter) rock on Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, which was taken in September and released today (Oct. 9). And it’s led to the decision to have an Egyptian theme to naming features on the comet.

“It stands out among a group of boulders in the smooth region located on the lower side of 67P/C-G’s larger lobe,” ESA stated in a release. “This cluster of boulders reminded scientists of the famous pyramids at Giza near Cairo in Egypt, and thus it has been named Cheops for the largest of those pyramids, the Great Pyramid, which was built as a tomb for the pharaoh Cheops (also known as Kheops or Khufu) around 2550 BC.”

Scientists are still trying to figure out what the boulders are made of, and how they are formed, as the spacecraft moves into a “close observation phase” tomorrow (Oct. 10) where it is only 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) from the surface.

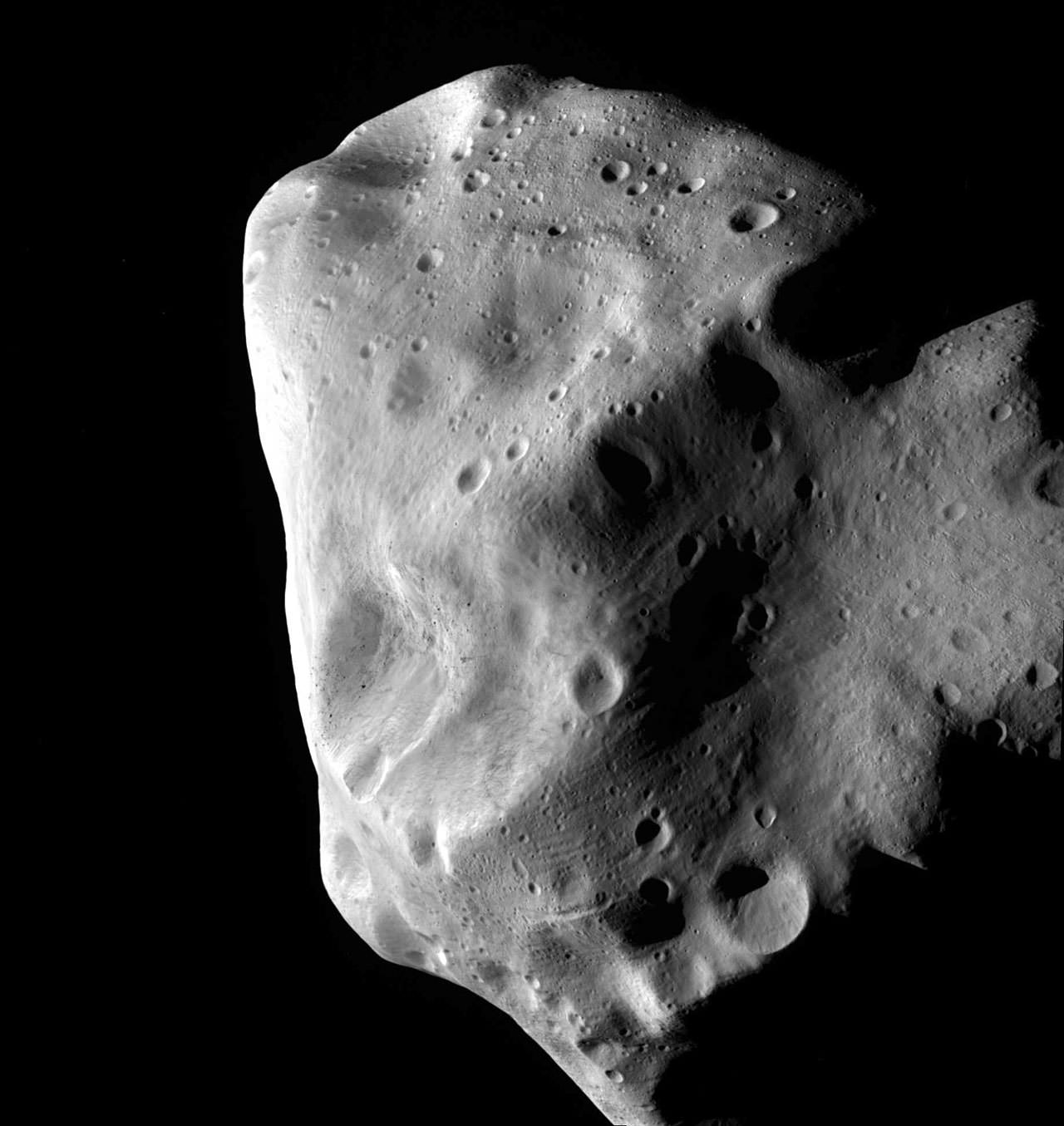

Meanwhile, some new results are coming from an asteroid that the spacecraft whizzed by a couple of years ago. In the picture below, you can see evidence of a crater that Rosetta didn’t even see!

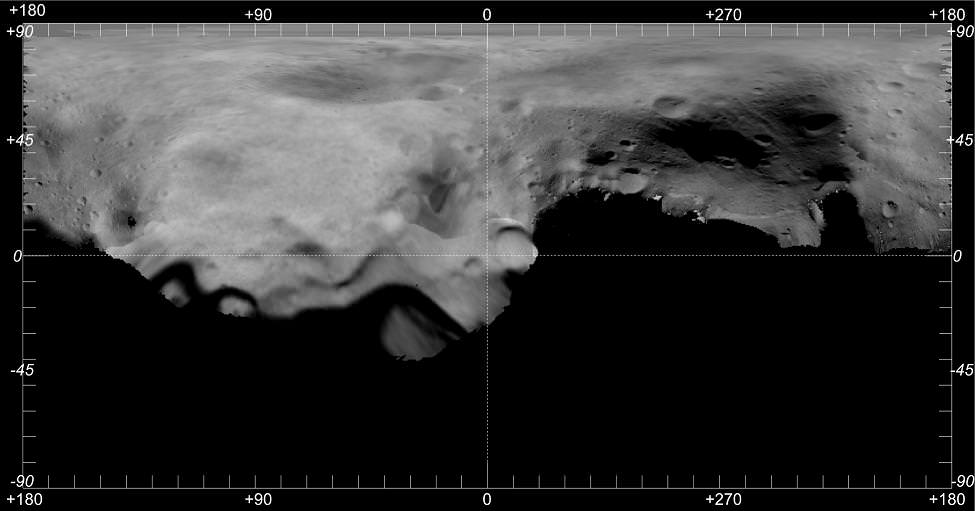

The grooves you see there on Lutetia (which Rosetta imaged in 2010) hint at shock waves from various craters, including one that was likely on the hidden side of the asteroid relative to Rosetta as it flew by. The suspected crater is called “Suspicio.” While craters have been found in other asteroids visited by spacecraft, grooves are rarer.

“The way in which grooves are formed on these bodies is still widely debated, but it likely involves impacts,” ESA stated. “Shock waves from the impact travel through the interior of a small, porous body and fracture the surface to form the grooves.”

A paper on the research will be published in Planetary and Space Science this month, led by Sebastien Besse, a research fellow at ESA’s Technical Centre. For more information, check out this release from ESA.