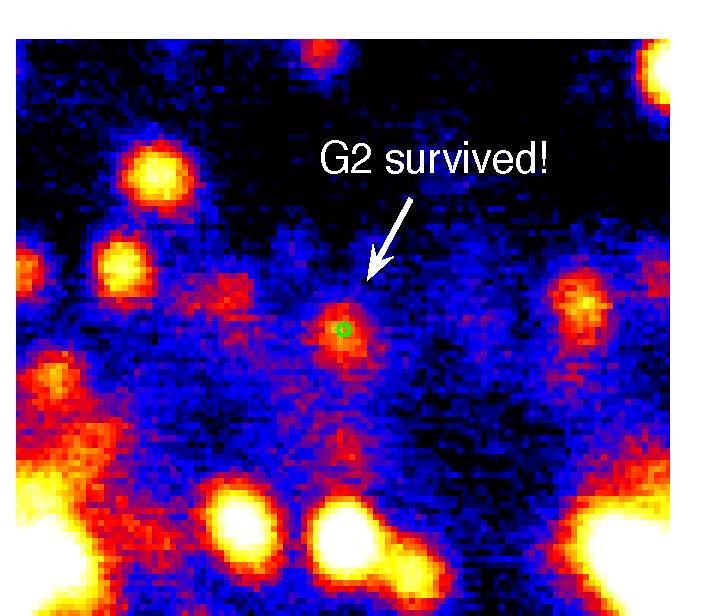

A mysterious object swinging around the supermassive black hole in the center our galaxy has surprised astronomers by actually surviving what many thought would be a devastating encounter. And with its survival, researchers have finally been able to solve the conundrum of what the object – known as G2 — actually is. Since G2 was discovered in 2011, there was a debate whether it was a huge cloud of hydrogen gas or a star surrounded by gas. Turns out, it was neither … or actually, all of the above, and more.

Astronomers now say that G2 is most likely a pair of binary stars that had been orbiting the black hole in tandem and merged together into an extremely large star, cloaked in gas and dust.

“G2 survived and continued happily on its orbit; a simple gas cloud would not have done that,” said Andrea Ghez from UCLA, who has led the observations of G2. “G2 was basically unaffected by the black hole. There were no fireworks.”

This was one of the “most watched” recent events in astronomy, since it was the first time astronomers have been able to view an encounter with a black hole like this in “real time.” The thought was that watching G2’s demise would not only reveal what this object was, but also provide more information on how matter behaves near black holes and how supermassive black holes “eat” and evolve.

Using the Keck Observatory, Ghez and her team have been able to keep an eye on G2’s movements and how the black hole’s powerful gravitational field affected it.

While some researchers initially thought G2 was a gas cloud, others argued that they weren’t seeing the amount of stretching or “spaghettification” that would be expected if this was just a cloud of gas.

As Ghez told Universe Today earlier this year, she thought it was a star. “Its orbit looks so much like the orbits of other stars,” she said. “There’s clearly some phenomenon that is happening, and there is some layer of gas that’s interacting because you see the tidal stretching, but that doesn’t prevent a star being in the center.”

Now, after watching the object the past few months, Ghez said G2 appears to be just one of an emerging class of stars near the black hole that are created because the black hole’s powerful gravity drives binary stars to merge into one. She also noted that, in our galaxy, massive stars primarily come in pairs. She says the star suffered an abrasion to its outer layer but otherwise will be fine.

Ghez explained in a UCLA press release that when two stars near the black hole merge into one, the star expands for more than 1 million years before it settles back down.

“This may be happening more than we thought. The stars at the center of the galaxy are massive and mostly binaries,” she said. “It’s possible that many of the stars we’ve been watching and not understanding may be the end product of mergers that are calm now.”

Ghez and her colleagues also determined that G2 appears to be in that inflated stage now and is still undergoing some spaghettification, where it is being elongated. At the same time, the gas at G2’s surface is being heated by stars around it, creating an enormous cloud of gas and dust that has shrouded most of the massive star.

Usually in astrophysics, timescales of events taking place are very long — not over the course of several months. But it’s important to note that G2 actually made this journey around the galactic center around 25,000 years ago. Because of the amount of time it takes light to travel, we can only now observe this event which happened long ago.

“We are seeing phenomena about black holes that you can’t watch anywhere else in the universe,” Ghez added. “We are starting to understand the physics of black holes in a way that has never been possible before.”

The research has been published in the journal Astrophysical Journal Letters.