When a star suffered an untimely demise at the hands of a hidden black hole, astronomers detected its doleful, ululating wail — in the key of D-sharp, no less — from 3.9 billion light-years away. The resulting ultraluminous X-ray blast revealed the supermassive black hole’s presence at the center of a distant galaxy in March of 2011, and now that information could be used to study the real-life workings of black holes, general relativity, and a concept first proposed by Einstein in 1915.

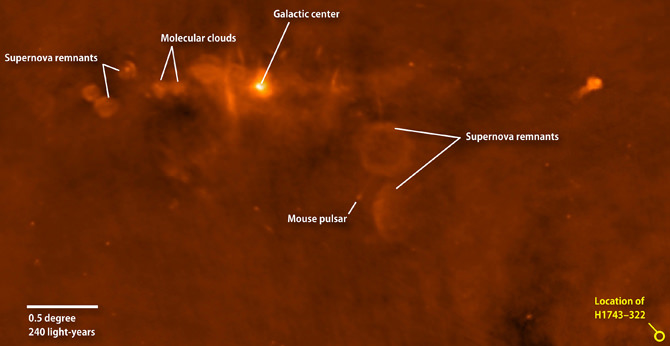

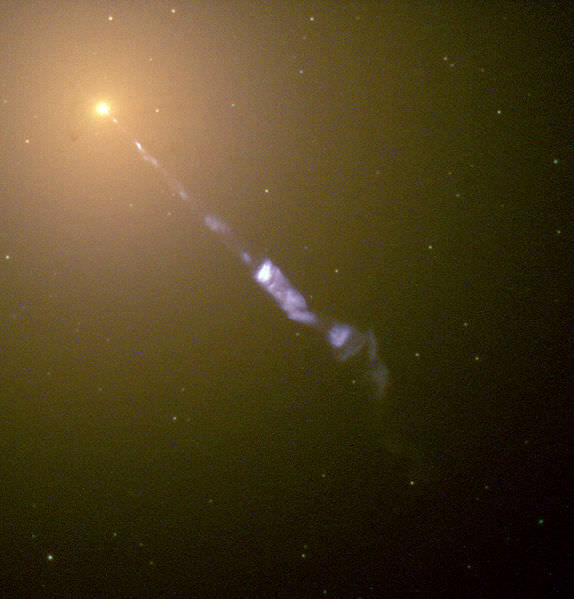

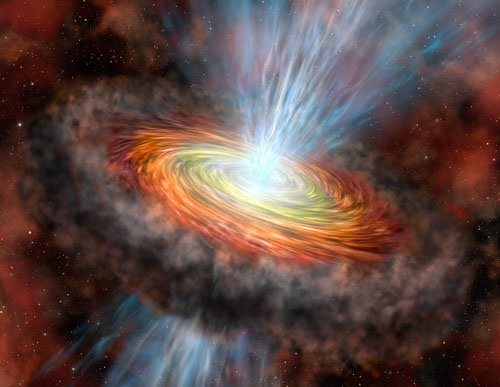

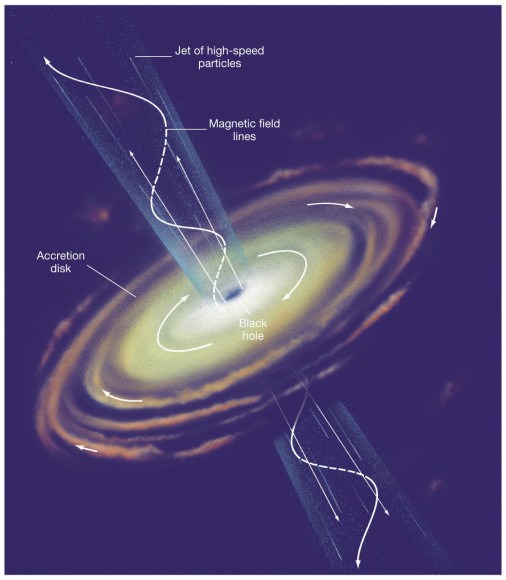

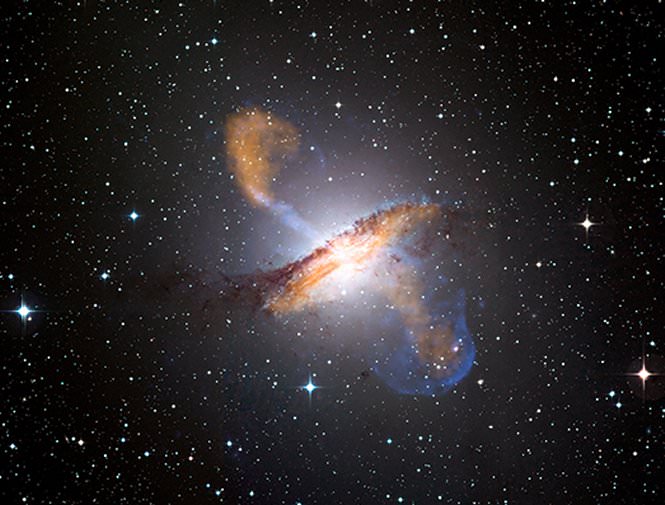

Within the centers of many spiral galaxies (including our own) lie the undisputed monsters of the Universe: incredibly dense supermassive black holes, containing the equivalent masses of millions of Suns packed into areas smaller than the diameter of Mercury’s orbit. While some supermassive black holes (SMBHs) surround themselves with enormous orbiting disks of superheated material that will eventually spiral inwards to feed their insatiable appetites — all the while emitting ostentatious amounts of high-energy radiation in the process — others lurk in the darkness, perfectly camouflaged against the blackness of space and lacking such brilliant banquet spreads. If any object should find itself too close to one of these so-called “inactive” stellar corpses, it would be ripped to shreds by the intense tidal forces created by the black hole’s gravity, its material becoming an X-ray-bright accretion disk and particle jet for a brief time.

Such an event occurred in March 2011, when scientists using NASA’s Swift telescope detected a sudden flare of X-rays from a source located nearly 4 billion light-years away in the constellation Draco. The flare, called Swift J1644+57, showed the likely location of a supermassive black hole in a distant galaxy, a black hole that had until then remained hidden until a star ventured too close and became an easy meal.

See an animation of the event below:

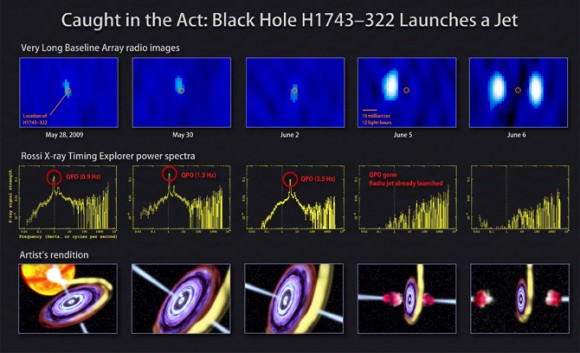

The resulting particle jet, created by material from the star that got caught up in the black hole’s intense magnetic field lines and was blown out into space in our direction (at 80-90% the speed of light!) is what initially attracted astronomers’ attention. But further research on Swift J1644+57 with other telescopes has revealed new information about the black hole and what happens when a star meets its end.

(Read: The Black Hole that Swallowed a Screaming Star)

In particular, researchers have identified what’s called a quasi-periodic oscillation (QPO) embedded inside the accretion disk of Swift J1644+57. Warbling at 5 mhz, in effect it’s the low-frequency cry of a murdered star. Created by fluctuations in the frequencies of X-ray emissions, such a source near the event horizon of a supermassive black hole can provide clues to what’s happening in that poorly-understood region close to a black hole’s point-of-no-return.

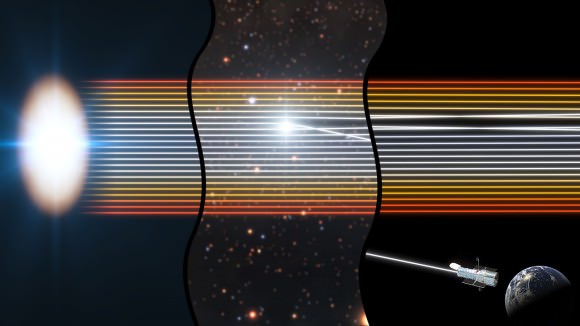

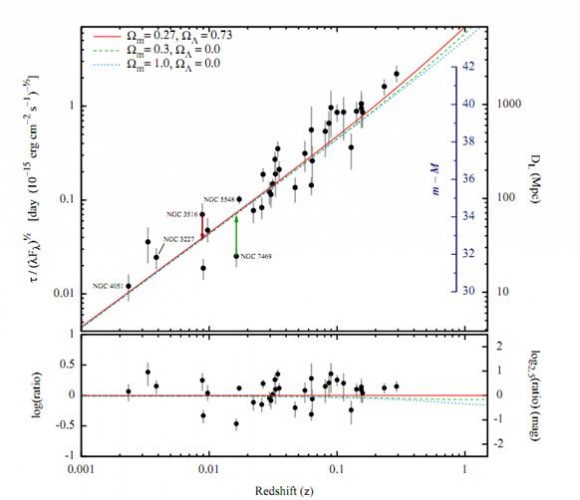

Einstein’s theory of general relativity proposes that space itself around a massive rotating object — like a planet, star, or, in an extreme instance, a supermassive black hole — is dragged along for the ride (the Lense-Thirring effect.) While this is difficult to detect around less massive bodies a rapidly-rotating black hole would create a much more pronounced effect… and with a QPO as a benchmark within the SMBH’s disk the resulting precession of the Lense-Thirring effect could, theoretically, be measured.

If anything, further investigations of Swift J1644+57 could provide insight to the mechanics of general relativity in distant parts of the Universe, as well as billions of years in the past.

See the team’s original paper here, lead authored by R.C. Reis of the University of Michigan.

Thanks to Justin Vasel for his article on Astrobites.

Image: NASA. Video: NASA/GSFC