[/caption]

Have you ever wondered how long it might take to travel to Mercury? At its closest point, Mercury gets to within 77.3 million km away from the Earth. Let’s see how long it takes for various spacecraft to get to Mercury.

For starters, let’s look at how long light itself takes to make the journey. Light takes only 4.3 minutes to travel from the Earth to Mercury when they’re at their closest point.

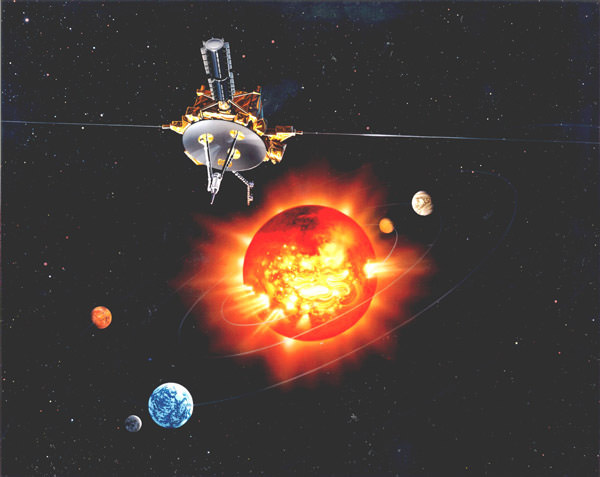

The fastest spacecraft ever launched from Earth is NASA’s New Horizons mission, currently on its way to visit Pluto and the outer Solar System. New Horizons is traveling at about 80,000 kilometers per hour. It would take about 40 days to get from the Earth to Mercury when they’re closest.

Of course, spacecraft don’t travel a straight route between planets, they follow a path that uses the least amount of energy, and so it takes them longer… a lot longer. The first spacecraft to actually make the journey to Mercury was NASA’s Mariner 10, which launched on November 3, 1973. It made its first Mercury flyby on March 29, 1974. Mariner 10 took 147 days to get from Earth to Mercury.

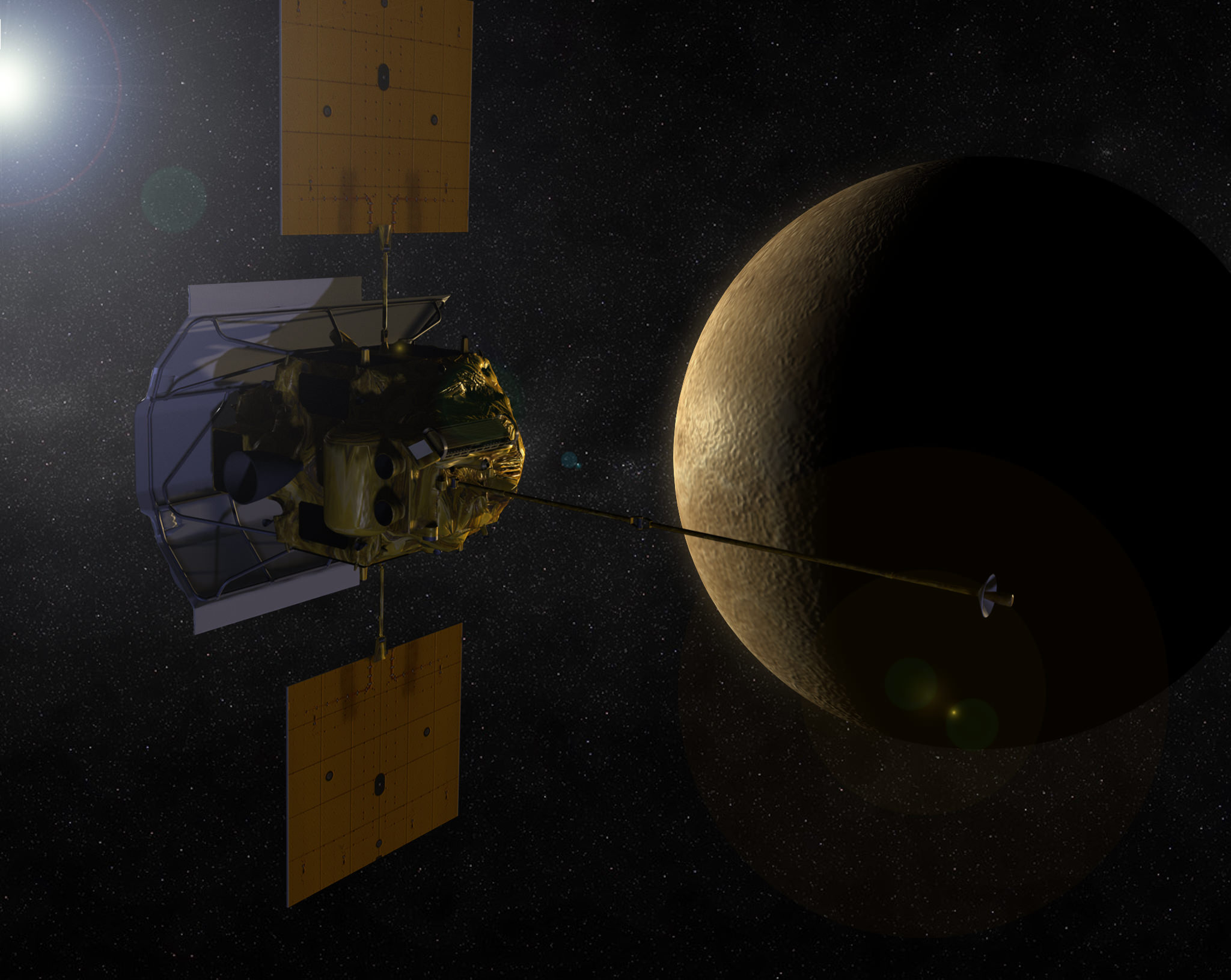

More recently, NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft launched on August 3, 2004 to study Mercury in orbit. It made its first flyby on January 14th, 2008. That’s a total of 1,260 days to get from Earth to Mercury. So why did MESSENGER take so long? Engineers want the spacecraft to go into orbit around Mercury, and so it needs to be traveling at a slow enough velocity to be able to get into orbit without just flying past. It will finally enter orbit around Mercury in March, 2011.

We have written many stories about Mercury here on Universe Today. Here’s an article about a side of Mercury never before seen by spacecraft, and how Mercury is actually less like the Moon than previously believed.

If you’d like more information on Mercury, check out NASA’s Solar System Exploration Guide, and here’s a link to NASA’s MESSENGER Misson Page.

We have also recorded a whole episode of Astronomy Cast that’s just about planet Mercury. Listen to it here, Episode 49: Mercury.

Cuánto tiempo toma llegar a Mercurio

References:

NASA: Mariner 10

NASA Messenger Mission Page