[/caption]

A high-school student from West Virginia has discovered a new astronomical object, a strange type of neutron star called a rotating radio transient. Lucas Bolyard, a sophomore at South Harrison High School in Clarksburg, WV, made the discovery while participating in a project in which students are trained to search through data from the Robert C. Byrd Green Bank Telescope (GBT). Bolyard made the discovery in March, after he already had studied more than 2,000 data plots from the GBT and found nothing.

The project is the Pulsar Search Collaboratory (PSC), which allows students to do real scientific research by looking at data from the GBT, the largest radio telescope in the US.

“Lucas is one of the most enthusiastic students involved in the project,” said Duncan Lorimer, astronomer from West Virginia University. “He’s one of these youngsters that never gives up, he’s very persistent and he has all the attributes that a scientist should have.”

Rotating radio transients are thought to be similar to pulsars, superdense neutron stars that are the corpses of massive stars that exploded as supernovae. Pulsars are known for their lighthouse-like beams of radio waves that sweep through space as the neutron star rotates, creating a pulse as the beam sweeps by a radio telescope. While pulsars emit these radio waves continuously, rotating radio transients emit only sporadically, one burst at a time, with as much as several hours between bursts. Because of this, they are difficult to discover and observe, with the first one only discovered in 2006.

“This neutron star is rotating very rapidly, so you have something the size of city with the mass of the sun, spinning incredibly rapidly,” said Lorimer “which also has an incredibly large magnetic field which is how we detect it with radio telescopes.”

“These objects are very interesting, both by themselves and for what they tell us about neutron stars and supernovae,” said Maura McLaughlin, also from WVU. “We don’t know what makes them different from pulsars — why they turn on and off. If we answer that question, it’s likely to tell us something new about the environments of pulsars and how their radio waves are generated.”

“They also tell us there are more neutron stars than we knew about before, and that means there are more supernova explosions. In fact, we now almost have more neutron stars than can be accounted for by the supernovae we can detect,” she added.

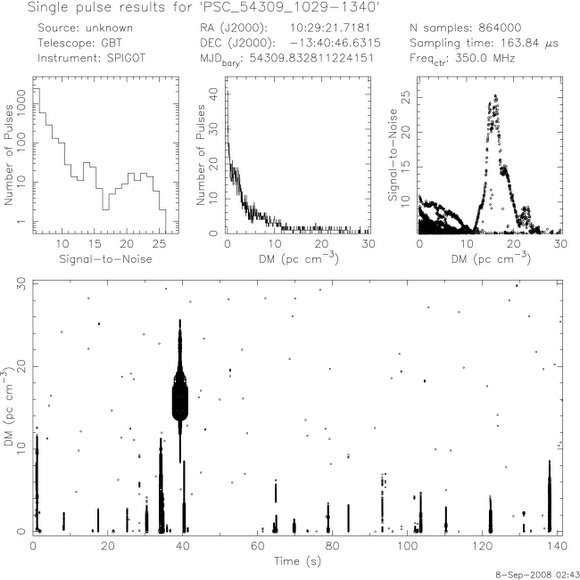

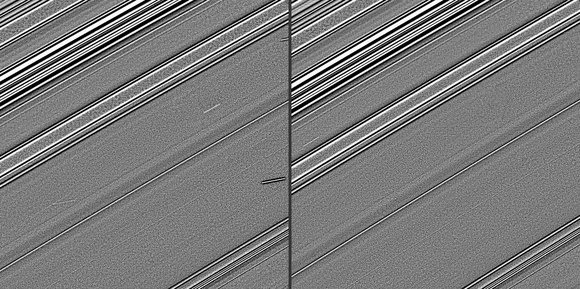

“I was home on a weekend and had nothing to do, so I decided to look at some more plots from the GBT,” Bolyard said. “I saw a plot with a pulse, but there was a lot of radio interference, too. The pulse almost got dismissed as interference,” he added.

Nonetheless, he reported it, and it went on a list of candidates for McLaughlin and Lorimer to re-examine, scheduling new observations of the region of sky from which the pulse came. Disappointingly, the follow-up observations showed nothing, indicating that the object was not a normal pulsar. However, the astronomers explained to Bolyard that his pulse still might have come from a rotating radio transient.

Confirmation didn’t come until July. Bolyard was at the NRAO’s Green Bank Observatory with fellow PSC students. The night before, the group had been observing with the GBT in the wee hours, and all were very tired. Then Lorimer showed Bolyard a new plot of his pulse, reprocessed from raw data, indicating that it is real, not interference, and that Bolyard is likely the discoverer of one of only about 30 rotating radio transients known.

Suddenly, Bolyard said, he wasn’t tired anymore. “That news made me full of energy,” he exclaimed. “My friends were really excited because they think I’m going to be famous!”

As of a year ago, Bolyard said he wouldn’t have thought of becoming astronomer, but this has given him second thoughts. “Making this discovery has made me very excited to get into a scientific field,” he said. “It’s a lot of hard work, but it’s worth it.”

The PSC, led by NRAO Education Officer Sue Ann Heatherly and Project Director Rachel Rosen, includes training for teachers and student leaders, and provides parcels of data from the GBT to student teams. The project involves teachers and students in helping astronomers analyze data from 1500 hours of observing with the GBT. The 120 terabytes of data were produced by 70,000 individual pointings of the giant, 17-million-pound telescope. Some 300 hours of the observing data were reserved for analysis by student teams.

Learn more about the PSC and Bolyard’s discovery on the Sept. 18 edition of 365 Days of Astronomy.

NRAO has a video about the discovery.

The student teams use analysis software to reveal evidence of pulsars. Each portion of the data is analyzed by multiple teams. In addition to learning to use the analysis software, the student teams also must learn to recognize man-made radio interference that contaminates the data. The project will continue through 2011.

“The students get to actually look through data that has never been looked through before,” Rosen said. From the training, she added, “the students get a wonderful grasp of what they’re looking at, and they understand the science behind the plots that they’re looking at.”

Source: NRAO