[/caption]

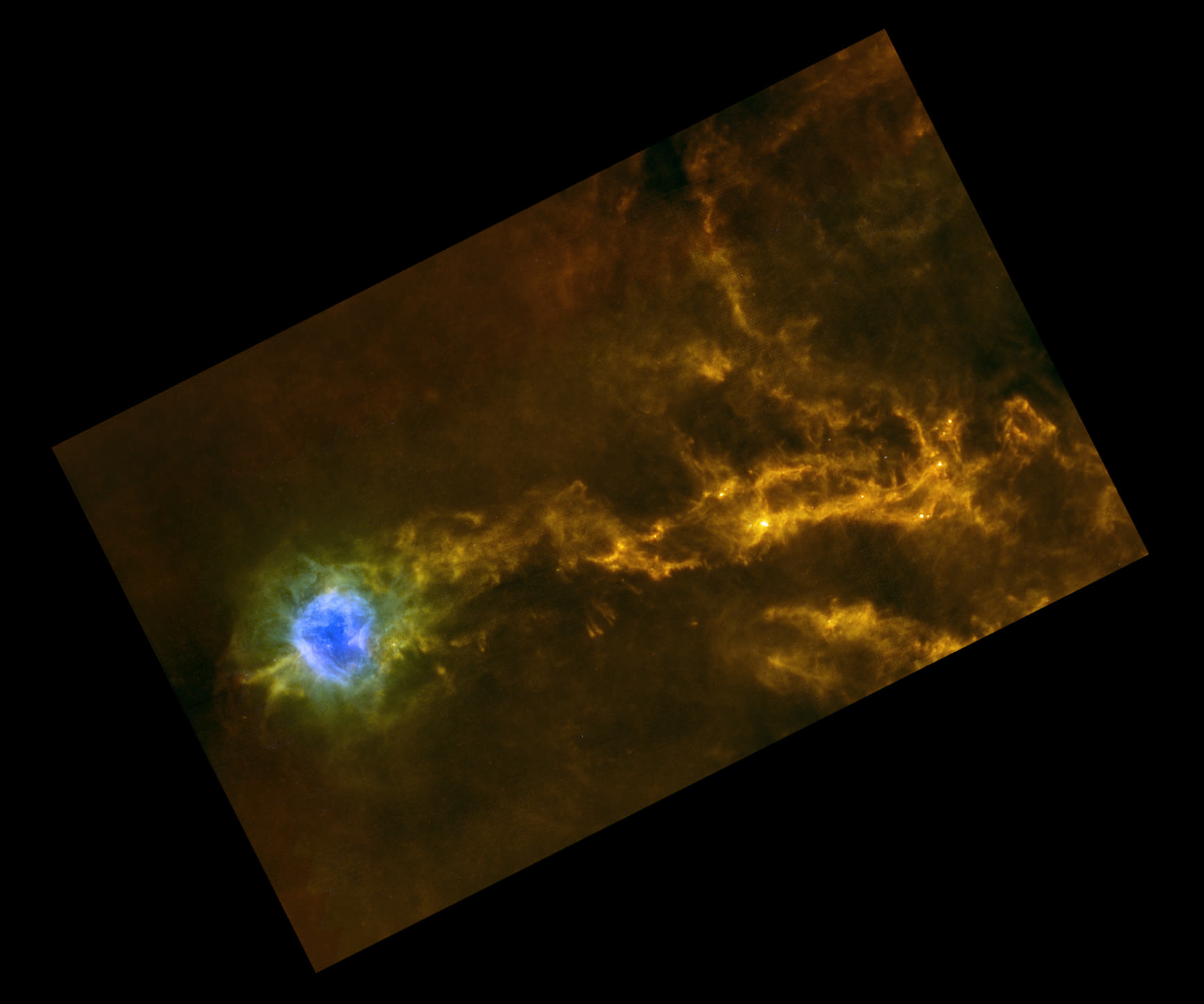

Star formation is an incredible process, but also notoriously difficult to trace. The reason is that the main constituent of stars, hydrogen, looks about the same well before a gravitational collapse begins, as it does in the dense clouds where star formation happens. Sure, the temperature changes and the hydrogen glows in a different part of the spectrum, but it’s still hydrogen. It’s everywhere!

So when astronomers want to search for denser regions of gas, they often turn to other atoms and molecules that can only form or be stimulated to emit under these relatively dense conditions. Common examples of this include carbon monoxide and hydrogen cyanide. However, a study published in 2005, led by David Meier at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, studied inner regions of the nearby face-on spiral by tracing eight molecules and determined that the full extent of the dense regions is not well mapped by these two common molecules. In particular, cyanoacetylene, an organic molecule with a chemical formula of HC3N, was demonstrated to correlate with the most active star forming regions, promising astronomers a peek into the heart of star forming regions and prompting a follow-up study.

The new study was conducted from the Very Large Array in late 2005. Specifically, it studied the emissions due to 5-4, 10-9, and 16-15 transitions which each correspond to different levels of heating and excitation. The dense regions uncovered by this study were consistent with the ones reported in 2005. One, discovered by the previous survey from another tracer molecule, was not found by this most recent study, but the new study also discovered a previously unnoticed giant molecular cloud (GMC) through the presence of HC3N.

Another technique that can be applied is examining the ratios of various levels of excitation. From this, astronomers can determine the temperature and density necessary to produce such emission. This can be performed with any type of gas, but using additional species of molecules provides independent checks on this value. For the area with the strongest emission, the team reported that the gas appeared to be a cool 40 K (-387°F) with a density of 1-10 thousand molecules per cubic centimeter. This is relatively dense for the interstellar medium, but for comparison, the air we breathe has approximately 1025 molecules per cubic centimeter. These findings are consistent with those reported from carbon monoxide.

The team also examined several of the star forming cores independently. By comparing the varying strengths of tracer molecules, the team was able to report that one GMC was well progressed in making stars while another was less evolved, likely still containing hot cores which had not yet ignited fusion. In the former, the HC3N is weaker than in the other cores explored, which the team attributes to the destruction of the molecules or dispersal of the cloud as fusion begins in the newly formed stars.

While using HC3N as a tracer is a relatively new approach (these studies of IC 342 are the first conduced in another galaxy), the results of this study have demonstrated that it can trace various features in dense clouds in similar fashions to other molecules.