Over the weekend, multiple space agencies’ had their instruments fixed on the skies as they waited for the Tiangong-1 space station to reenter our atmosphere. For the sake of tracking the station’s reentry, the ESA hosted the 2018 Inter Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee, an annual exercise that consists of experts from 13 space agencies taking part in a joint tracking exercise.

And on April 2nd, 02:16 CEST (April 1st, 17:16 PST), the US Air Force confirmed the reentry of the Tiangong-1 over the Pacific Ocean. As hoped, the station crashed down close to the South Pacific Ocean Unpopulated Area (SPOUA), otherwise known as the “Spaceship Cemetery”. This region of the Pacific Ocean has long been used by space agencies to dispose of spent spacecraft after a controlled reentry.

The confirmation came from the Joint Force Space Component Command (JFSCC) on April 2nd, 0:400 CEST (April 1st, 19:00 PST). Using the Space Surveillance Network sensors and their orbital analysis system, they were able to refine their predictions and provide more accurate tracking as the station’s reentry time approached. The USAF regularly shares information with the ESA regarding its satellites and debris tracking.

As with the ESA’s coordination with other space agencies and European member states, JFSCC’s efforts include counterparts in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, South Korea, and the United Kingdom. As Maj. Gen. Stephen Whiting, the Deputy Commander of the JFSCC and Commander of the 14th Air Force, indicated in a USAF press release:

“The JFSCC used the Space Surveillance Network sensors and their orbital analysis system to confirm Tiangong-1’s reentry, and to refine its prediction and ultimately provide more fidelity as the reentry time approached. This information is publicly-available on USSTRATCOM’s website www.Space-Track.org. The JFSCC also confirmed reentry through coordination with counterparts in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, South Korea, and the United Kingdom.”

The information is available on U.S. Strategic Command’s (USSTRATCOM) website – www.Space-Track.org. Holger Krag, the head of ESA’s Space Debris Office, confirmed the reentry of Tiangong-1 shortly thereafter on the ESA’s Rocket Science Blog. As he stated, the reentry was well within ESA’s earlier reentry forecast window – which ran from April 1st 23:00 UTC to 03:00 UTC on April 2nd (April 2nd, 01:00 CEST to 05:00 CEST):

“According to our experience, their assessment is very reliable. This corresponds to a geographic latitude of 13.6 degrees South and 164.3 degrees West – near American Samoa in the Pacific, near the international date Line. Both time and location are well within ESA’s last prediction window.”

China’s Manned Space Agency (CMSA) also made a public statement about the station’s reenty:

“According to the announcement of China Manned Space Agency (CMSA), through monitoring and analysis by Beijing Aerospace Control Center (BACC) and related agencies, Tiangong-1 reentered the atmosphere at about 8:15 am, 2 April, Beijing time. The reentry falling area located in the central region of South Pacific. Most of the devices were ablated during the reentry process.”

As Krag noted, the ESA’s monitoring efforts were very much reliant on its campaign partners from around the world. In fact, due to when the station entered the Earth’s atmosphere, it was no longer visible to the Fraunhofer FHR institute’s Tracking and Imaging (TIRA) radar, which provides tracking services for the ESA’s Space Debris Office (SDO).

Had the station still been in orbit by 06:05 CEST (21:00 PST), it would have still been visible to the institute’s TIRA radar. Some unexpected space weather also played a role in the station’s reentry. On March 31st, the Sun’s activity spontaneously dropped, which delayed the Tiangong-1’s entry by about a day.

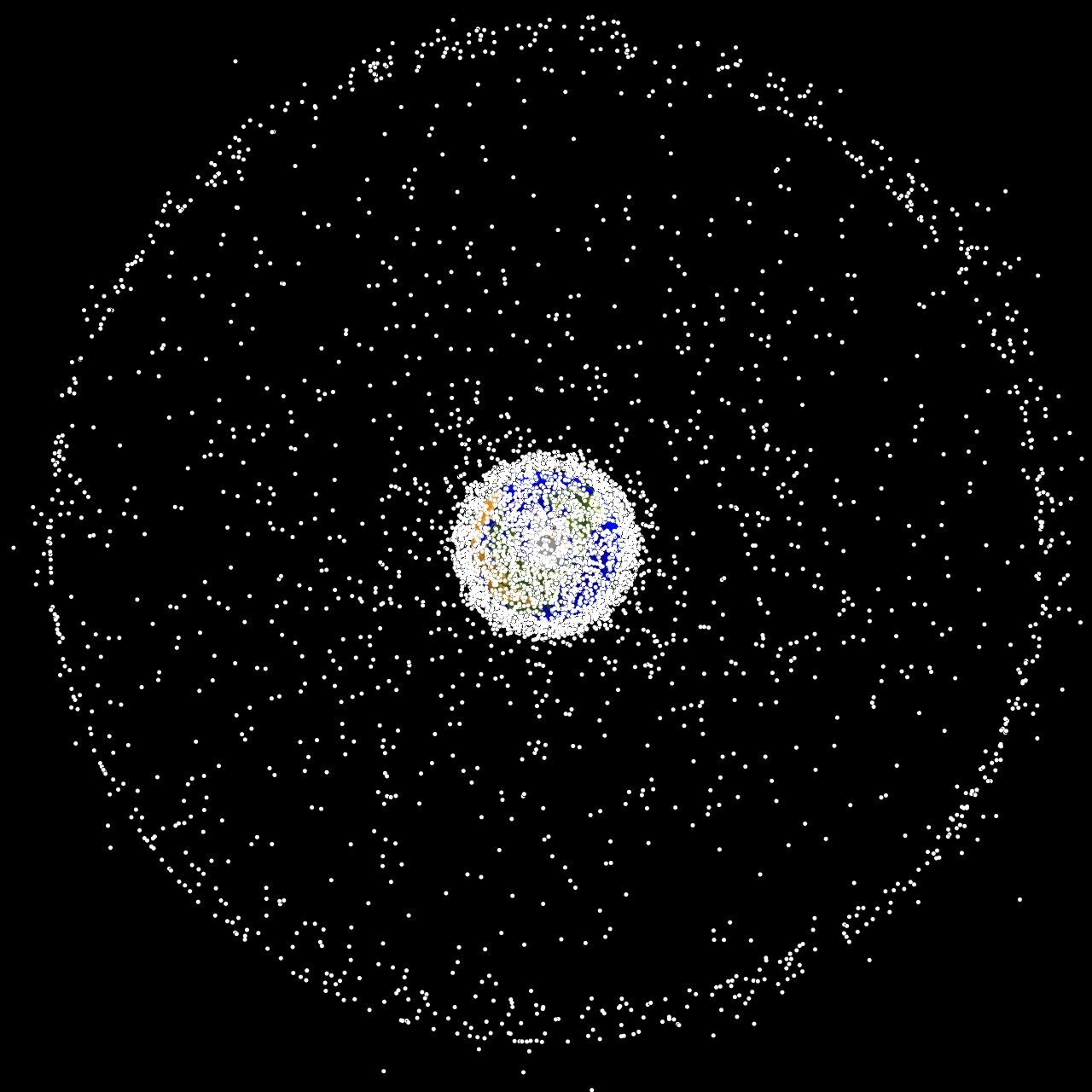

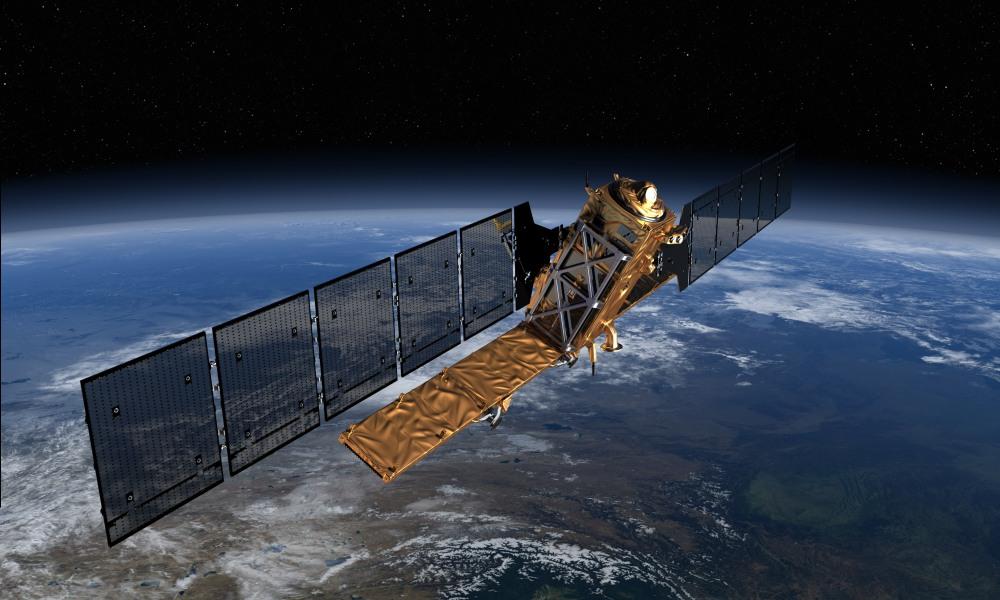

“This illustrates again the dependence that Europe has on non-European sources of information to properly and accurately manage space traffic, detect reentries such as Tiangong-1 and track space debris that remains in orbit – which routinely threatens ESA, European and other national civil, meteorological, scientific, telecomm and navigation satellites,” said Krag.

While news of the Tiangong-1’s orbital decay caused its share of concern, the reentry happened almost entirely as predicted and resulted in no harm. And once again, it demonstrated how international cooperation and public outreach is the best defense against space-related hazards.

Further Reading: Vandenburg Air Force Base,