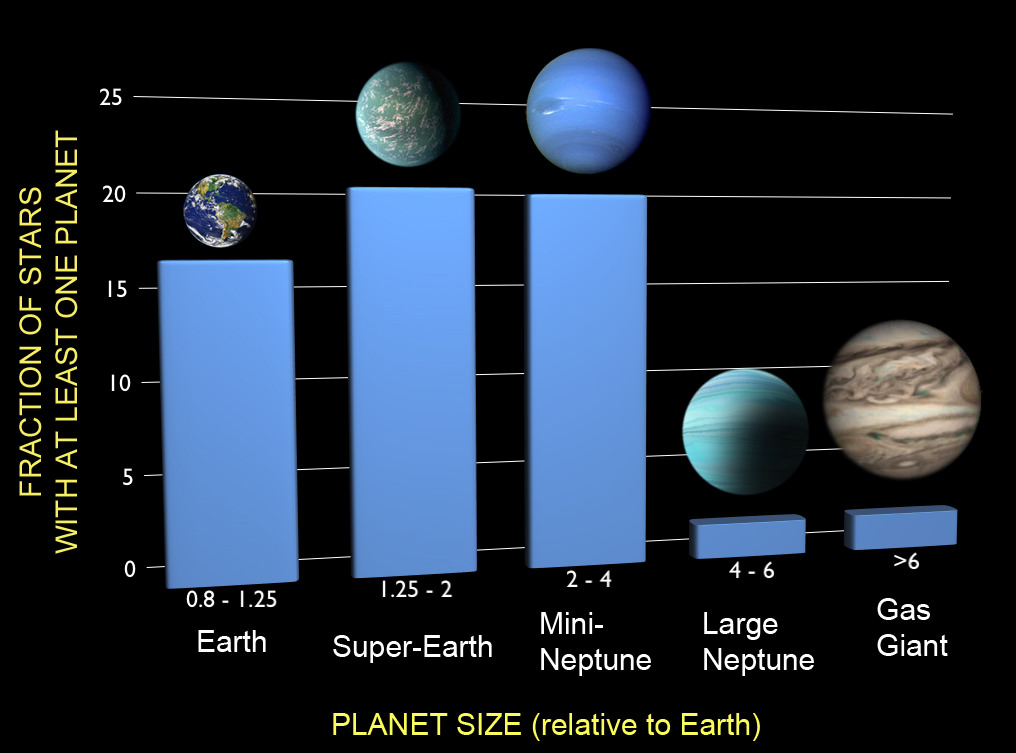

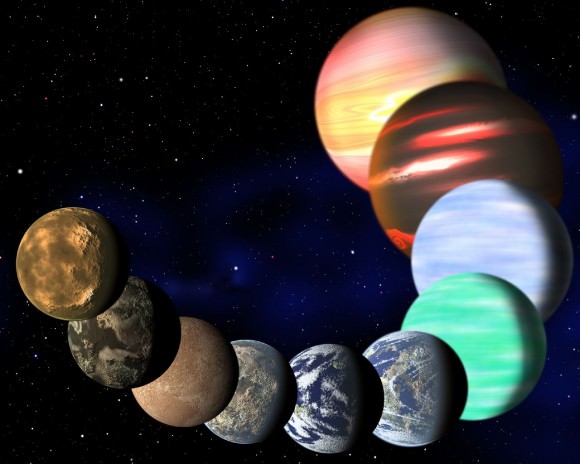

Recent findings say that Earth-like exoplanets could be all around us in our cosmic neighborhood. But how many would be home to intelligent life?

A new study estimates that fewer than 1% of transiting exoplanet systems host civilizations technologically advanced enough to send out radio transmissions that could be detected by our current SETI searches.

That equates to less than one in a million stars in the Milky Way Galaxy that would have intelligent life we could possibly communicate with. But even with those odds, there could be millions of advanced ET’s in the galaxy that we could phone, researchers say.

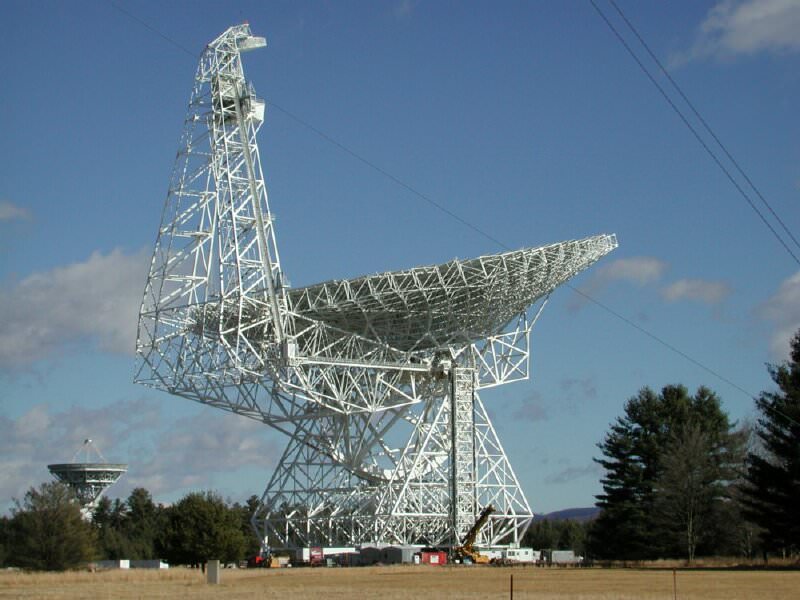

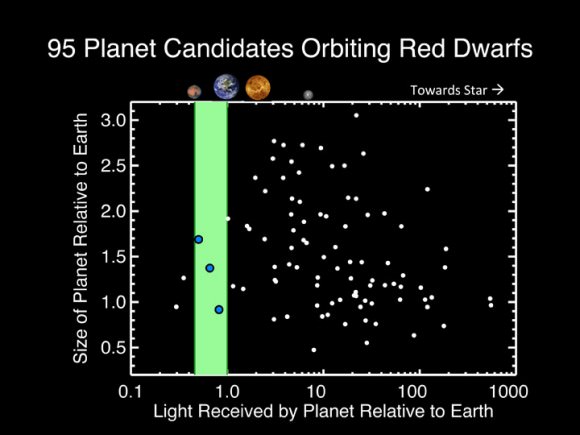

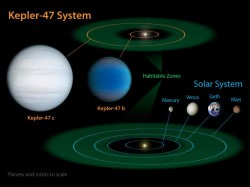

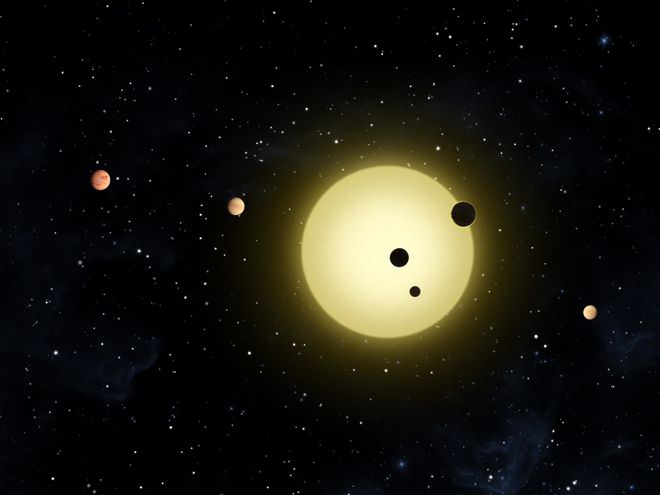

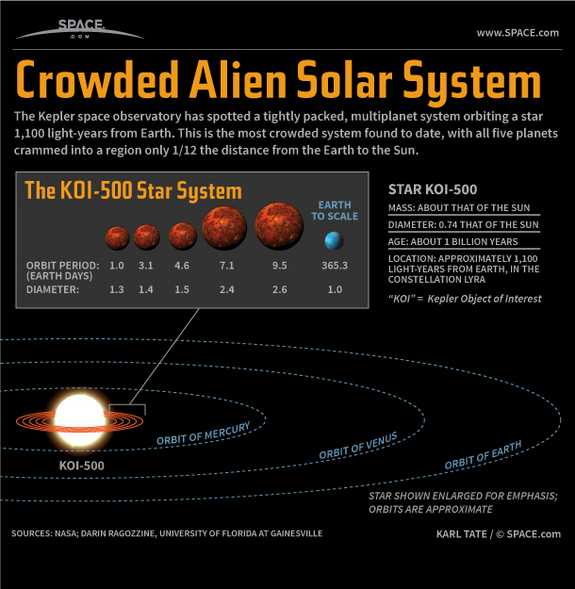

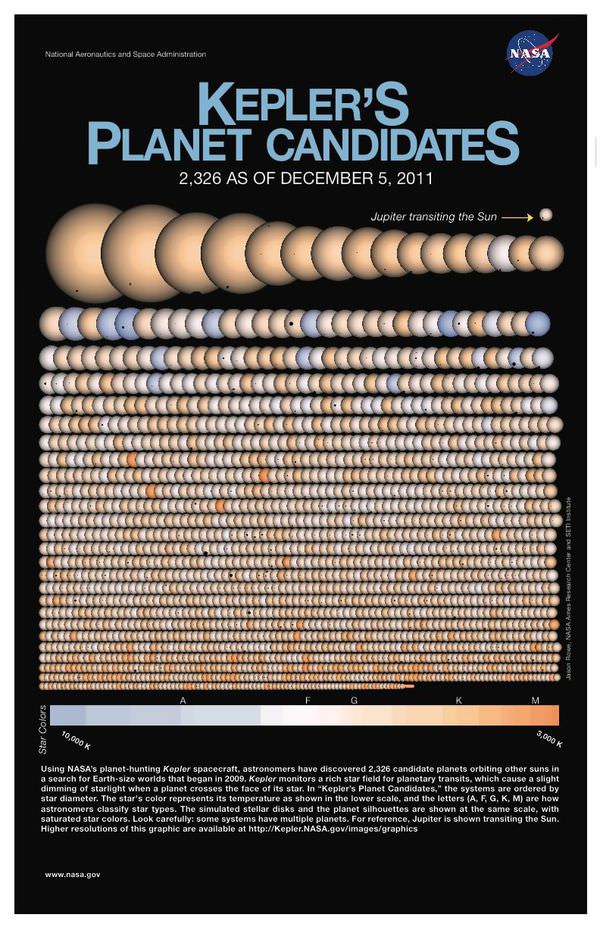

A group of astronomers, including Jill Tarter from the SETI Institute and scientists at the University of California, Berkeley used the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia to look for intelligent radio signals from planets around 86 of stars where the Kepler mission has found transiting exoplanets. These specific targets were chosen because they had exoplanets in the habitable zone around the star and there were either five or more exoplanets in the system, or there was super-Earths with relatively long orbits.

The search came up empty in detecting any signals.

“We didn’t find ET, but we were able to use this statistical sample to, for the first time, put rather explicit limits on the presence of intelligent civilizations transmitting in the radio band where we searched,” said Andrew Siemion from UC Berkeley.

The team looked for signals in the 1-2 GHz range which is the region we use here on Earth for our cell phones and television transmissions. Narrowing it down, the team looked for signals that cover no more than 5Hz of the spectrum since there is no known natural mechanism for producing such narrow band signals.

“Emission no more than a few Hz in spectral width is, as far as we know, an unmistakable indicator of engineering by an intelligent civilization,” the team said in their paper.

The telescope spent 12 hours collecting five minutes of radio emissions from each star. Most of the stars were more than 1,000 light-years away, so only signals intentionally aimed in our direction would have been detected. The scientists say that in the future, more sensitive radio telescopes, such as the Square Kilometer Array, should be able to detect much weaker radiation, perhaps even unintentional leakage radiation, from civilizations like our own.

The researchers said these results allows them to put limits on the likelihood of Kardashev Type II civilizations. The Karashev scale is a method of measuring a civilization’s level of technological advancement, based on the amount of energy a civilization is able to utilize. The team said that finding no signals implies that the number of these civilizations that are “noisy” in the 1-2GHz range must less than one in a million per sun-like star.

The team plans more observations with the Green Bank Telescope, focusing on multi-planet systems in which two of the planets occasionally align relative to Earth, potentially allowing them to eavesdrop on communications between the planets.

“This work illustrates the power of leveraging our latest understanding of exoplanets in SETI searches,” said UC Berkeley physicist Dan Werthimer, who heads the world’s longest running SETI project at the Arecibo Telescope in Puerto Rico. “We no longer have to guess about whether we are targeting Earth-like environments, we know it with certainty.”

Sources: UC Berkeley, MIT Technology Review