We hear about discoveries of exoplanets every day. So how long will it take us to find another planet like Earth?

There are two separate parts of your brain I would like to speak with today. First, I want to talk to the part that makes decisions on who to vote for, how much insurance you should put on your car and deals with how not paying taxes sends you to jail. We’ll call this part of your brain “Kevin”.

The rest of your brain can kick back, especially the parts that knows what kind of gas station you prefer, whether Lena Dunham is awesome or “the most awesome”, whether a certain sports team is the winningest, or believes that you can leave a casino with more money than you went in with. We will call this part “Other Kevin”, in honor of Dave Willis.

Okay Kevin, you’re up. I’m going to cut to the gut punch, Kevin. Between you and me, it is my displeasure to inform you that science fiction has ruined “Other Kevin”. Just like comic books have compromised their ability to judge the likelihood of someone acquiring heat vision, science fiction has messed up their sense of scale about interstellar travel.

But you already knew that. Not like “Other Kevin”, you’re the smart one. In the immortal words of Douglas Adams, “space is big”. But when he said that, Douglas was really understating how mind-bogglingly big space really is.

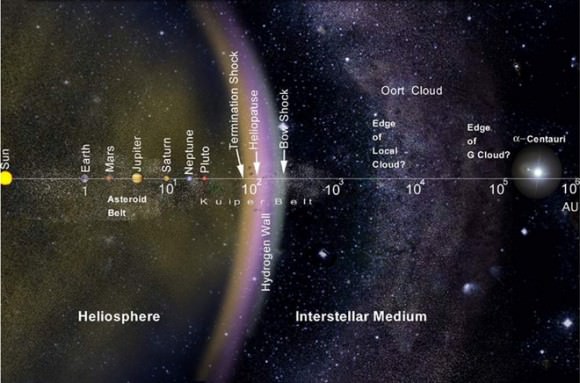

The nearest star is 4 light years away. That means that light, traveling at 300,000 kilometers per second would still need 4 YEARS to reach the nearest star. The fastest spacecraft ever launched by humans would need tens of thousands of years to make that trip.

But science fiction encourages us to think it’s possible. Kirk and Spock zip from world to world with a warp drive violating the Prime Directive right in it’s smug little Roddenberrian face. Han and Chewy can make the Kessel run in only 12 parsecs, which is confusing and requires fan theories to resolve the cognitive space-distance dissonance, and Galactica, The SDF 3, and Guild Navigators all participate in the folding of space.

And science fiction knows everything that’s about to happen, right? Like cellphones. Additionally Kevin, I know what you’re thinking and I’m not going to tear into Lucas on this. It’s too easy, and my ilk do it a little too often. Plus, I’m saving it up for Abrams. Sorry Kevin. Got a little distracted there.

The point is, science fiction is doing colossal hand waving. They’re glossing over key obstacles, like the laws of physics.

Stay with me here.This isn’t like jaywalking bylaws that “probably don’t apply to you at that very moment”, these are the physical laws of the universe that will deliver a complete junk-kicking if you try and pretend they’re not interested in crushing your little atmosphere requiring, century lifespan, conventional propulsion drive dreams.

So let’s say that we wanted to actually send a spacecraft to another star, whilst obeying the laws of physics. We’ll set the bar super low. We’re not talking about massive cruise ships filled with tourists seeking the delights of the super funzone planetoid, Itchy and Scrachylandia Prime.

I’m not talking about sending a crack team of power armored space marines to defend colonists from xenomorphs, or perhaps take other more thorough measures.

No, I’m talking about getting an operational teeny robotic spacecraft from Earth to Alpha Centauri. The fastest spacecraft we’ve ever launched is New Horizons. It’s currently traveling at 14 kilometres per second. It would take this peppy little probevette 100,000 years to get to the nearest star.

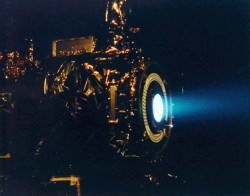

This is mostly due to our lack of reality shattering propulsion. Our best propellant option is an ion engine, used by NASA’s Dawn spacecraft. According to much adored Ian “Handsome” O’Neill from Discovery Space, we’d be looking at 19,000 years to get to Alpha Centauri if we used an ion engine and added a gravitational assist from the Sun.

Just think of what we could do with those 81,000 years we’d be saving! I’m going to learn the dulcimer!

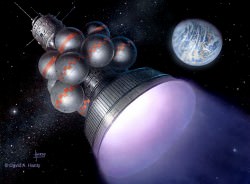

We can start shearing back the reality curtain and throw money and resources to chase nearby speculative propulsion tech. Things like antimatter engines, or even dropping nuclear bombs out the back of a spacecraft

The best idea in the hopper is to use solar sails, like the Planetary Society’s Lightsail.

Use the light from the Sun as well as powerful lasers to accelerate the craft.

But if we’re going to start down that road, we could also send microscopic lightsail spacecraft which are much easier to accelerate. Once these miniprobes reached their target, they could link up and form a communications relay, or even robotic factories.

Sorry, I think that was my “Other Kevin” talking. So where are we at, fo’ reals?

Harold “Sonny” White, a researcher with NASA announced that they’ve been testing out a futuristic technology called an EM drive. They detected a very slight “thrust” in their equipment that might mean it could be possible to maybe push a spacecraft in space without having to expel propellent like a chemical rocket or an ion drive.

What’s that, Kevin? Yes, you should totally be skeptical. You’re right, that last bit was a salad of weasel words.

Even if this crazy drive actually works, it still needs to obey the laws of physics. You couldn’t go faster than the speed of light and you would need a remarkable source of energy to power the reactor. Also, yes, Kevin, you’re right NASA is working on a warp drive. There’s no need to yell.

NASA is also working on an actual warp drive concept known as an alcubierre drive. It would actually do what science fiction has claimed: to warp space to allow faster than light travel. But by working on it, I mean, they’ve done a lot of fancy math.

But once they get all the math done, they can just go build it right? This concept is so theoretical that physicists are still arguing whether powering an alcubierre drive would take more energy than contained within the entire Universe. Which, I think we can call an obstacle.

Oh, one more thing. “Other Kevin”, thanks for being so patient. Here’s your reward. Unicorns are real, and Kevin has been lying to you this whole time. Go get ‘em tiger. Place your bets. When do you think we’ll send our first probe towards another star? Predict the departure date in the comments below.