The planets of our Solar System vary considerably in size and shape. Some planets are small enough that they are comparable in diameter to some of our larger moons – i.e. Mercury is smaller than Jupiter’s moon Ganymede and Saturn’s moon Titan. Meanwhile, others like Jupiter are so big that they are larger in diameter than most of the others combined.

In addition, some planets are wider at the equator than they are at the poles. This is due to a combination of the planets composition and their rotational speed. As a result, some planets are almost perfectly spherical while others are oblate spheroids (i.e. experience some flattening at the poles). Let us examine them one by one, shall we?

Mercury:

With a diameter of 4,879 km (3031.67 mi), Mercury is the smallest planet in our Solar System. In fact, Mercury is not much larger than Earth’s own Moon – which has a diameter of 3,474 km (2158.64 mi). At 5,268 km (3,273 mi) in diameter, Jupiter’s moon of Ganymede is also larger, as is Saturn’s moon Titan – which is 5,152 km (3201.34 mi) in diameter.

As with the other planets in the inner Solar System (Venus, Earth, and Mars), Mercury is a terrestrial planet, which means it is composed primarily of metals and silicate rocks that are differentiated into an iron-rich core and a silicate mantle and crust.

Also, due to the fact that Mercury has a very slow sidereal rotational period, taking 58.646 days to complete a single rotation on its axis, Mercury experiences no flattening at the poles. This means that the planet is almost a perfect sphere and has the same diameter whether it is measured from pole to pole or around its equator.

Venus:

Venus is often referred to as Earth’s “sister planet“, and not without good reason. At 12,104 km (7521 mi) in diameter, it is almost the same size as Earth. But unlike Earth, Venus experiences no flattening at the poles, which means that it almost perfectly circular. As with Mercury, this is due to Venus’ slow sidereal rotation period, taking 243.025 days to rotate once on its axis.

Earth:

With a mean diameter of 12,756 km (7926 mi), Earth is the largest terrestrial planet in the Solar System and the fifth largest planet overall. However, due to flattening at its poles (0.00335), Earth is not a perfect sphere, but an oblate spheroid. As a result, its polar diameter differs from its equatorial diameter, but only by about 41 km (25.5 mi)

In short, Earth measures 12713.6 km (7900 mi) in diameter from pole to pole, and 12756.2 km (7926.3 mi) around its equator. Once again, this is due to Earth’s sidereal rotational period, which takes a relatively short 23 hours, 58 minutes and 4.1 seconds to complete a single rotation on its axis.

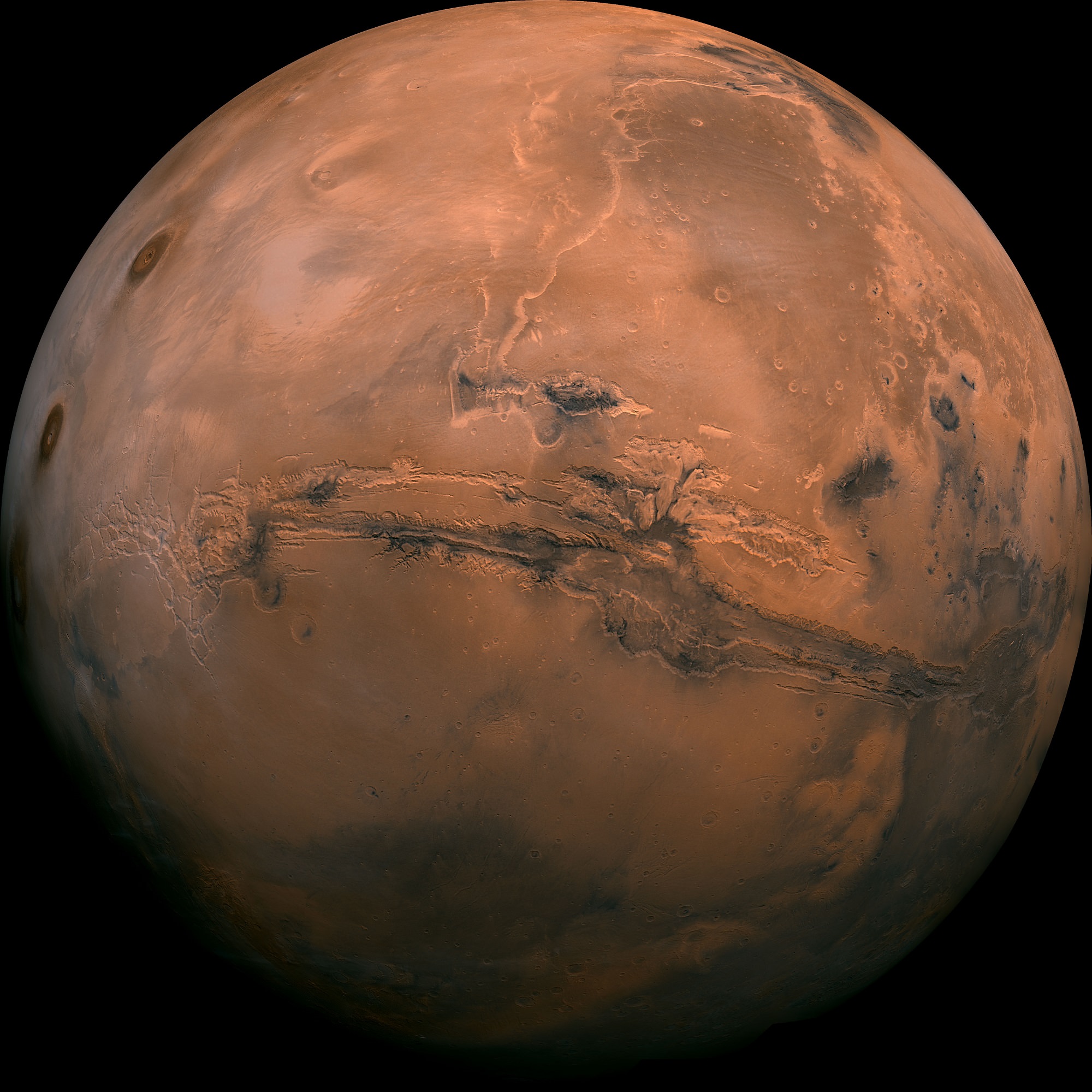

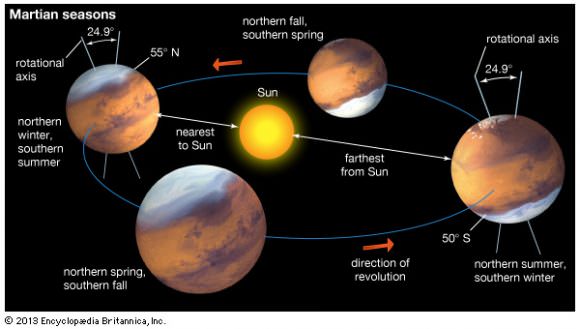

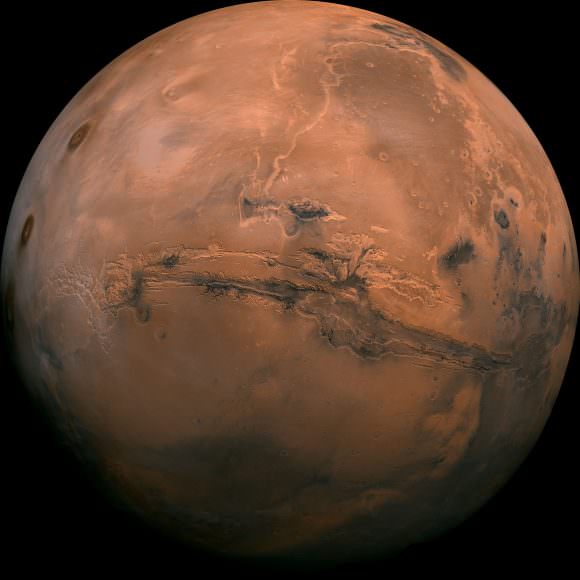

Mars:

Mars is often referred to as “Earth’s twin”; and again, for good reason. Like Earth, Mars experiences flattening at its poles (0.00589), which is due to its relatively rapid sidereal rotational period (24 hours, 37 minutes and 22 seconds, or 1.025957 Earth days).

As a result, it experiences a bulge at its equator which leads to a variation of 40 km (25 mi) between its polar radius and equatorial radius. This works out to Mars having a mean diameter of 6779 km (4212.275 mi), varying between 6752.4 km (4195.75 mi) between its poles and 6792.4 km (4220.6 mi) at its equator.

Jupiter:

Jupiter is the largest planet in the Solar System, measuring some 142,984 km (88,846 mi) in diameter. Again, this its mean diameter, since Jupiter experiences some rather significant flattening at the poles (0.06487). This is due to its rapid rotational period, with Jupiter taking just 9 hours 55 minutes and 30 seconds to complete a single rotation on its axis.

Combined with the fact that Jupiter is a gas giant, this means the planet experiences significant bulging at its equator. Basically, it varies in diameter from 133,708 km (83,082.3 mi) when measured from pole to pole, and 142,984 km (88,846 mi) when measured around the equator. This is a difference of 9276 km (5763.8 mi), one of the most pronounced in the Solar System.

Saturn:

With a mean diameter of 120,536 km (74897.6 mi), Saturn is the second largest planet in the Solar System. Like Jupiter, it experiences significant flattening at its poles (0.09796) due to its high rotational velocity (10 hours and 33 minutes) and the fact that it is a gas giant. This means that it varies in diameter from 108,728 km (67560.447 mi) when measured at the poles and 120,536 km (74,897.6 mi) when measured at the equator. This is a difference of almost 12,000 km, the greatest of all planets.

Uranus:

Uranus has a mean diameter of 50,724 km (31,518.43 mi), making it the third largest planet in the Solar System. But due to its rapid rotational velocity – the planet takes 17 hours 14 minutes and 24 seconds to complete a single rotation – and its composition, the planet experiences a significant polar flattening (0.0229). This leads to a variation in diameter of 49,946 km (31,035 mi) at the poles and 51,118 km (31763.25 mi) at the equator – a difference of 1172 km (728.25 mi).

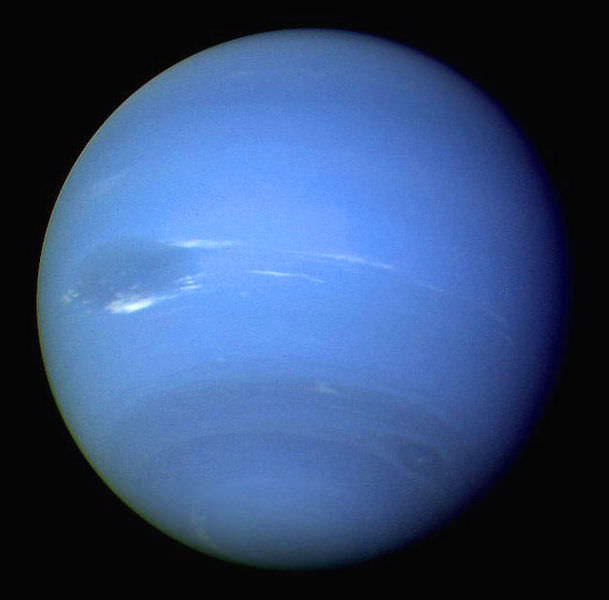

Neptune:

Lastly, there is Neptune, which has a mean diameter of 49,244 km (30598.8 mi). But like all the other gas giants, this varies due to its rapid rotational period (16 hours, 6 minutes and 36 seconds) and composition, and subsequent flattening at the poles (0.0171). As a result, the planet experiences a variation of 846 km (525.68 mi), measuring 48,682 km (30249.59 mi) at the poles and 49,528 km (30775.27 mi) at the equator.

In summary, the planets of our Solar System vary in diameter due to differences in their composition and the speed of their rotation. In short, terrestrial planets tend to be smaller than gas giants, and gas giants tend to spin faster than terrestrial worlds. Between these two factors, the worlds we know range between near-perfect spheres and flattened spheres.

We have written many articles about the Solar System here at Universe Today. Here’s Interesting Facts about the Solar System, How Long Is A Day On The Other Planets Of The Solar System?, What Are the Colors of the Planets?, How Long Is A Year On The Other Planets?, What Is The Atmosphere Like On Other Planets?, and How Strong is Gravity on Other Planets?

For more information of the planets, here is a look at the eight planets and some fact sheets about the planets from NASA.

Astronomy Cast has episodes on all the planets. Here is Mercury to start out with.