What is the Universe? That is one immensely loaded question! No matter what angle one took to answer that question, one could spend years answering that question and still barely scratch the surface. In terms of time and space, it is unfathomably large (and possibly even infinite) and incredibly old by human standards. Describing it in detail is therefore a monumental task. But we here at Universe Today are determined to try!

So what is the Universe? Well, the short answer is that it is the sum total of all existence. It is the entirety of time, space, matter and energy that began expanding some 13.8 billion years ago and has continued to expand ever since. No one is entirely certain how extensive the Universe truly is, and no one is entirely sure how it will all end. But ongoing research and study has taught us a great deal in the course of human history.

Definition:

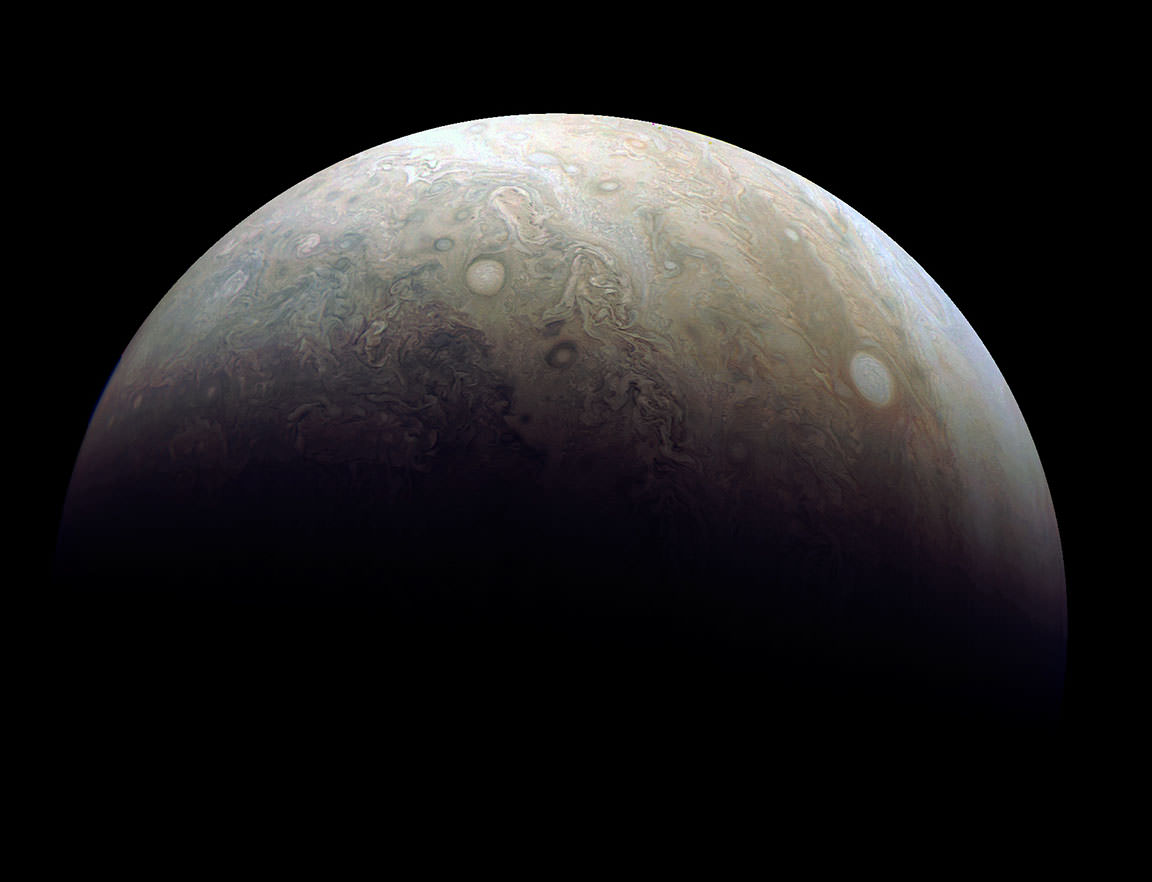

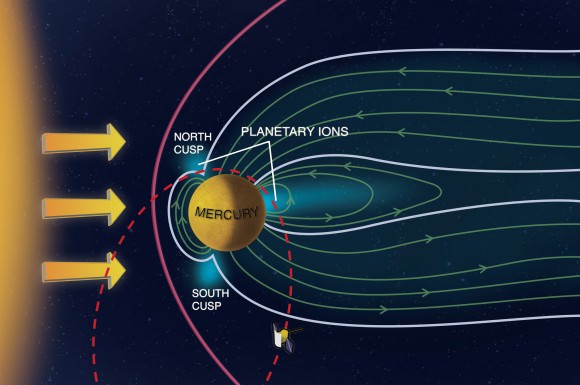

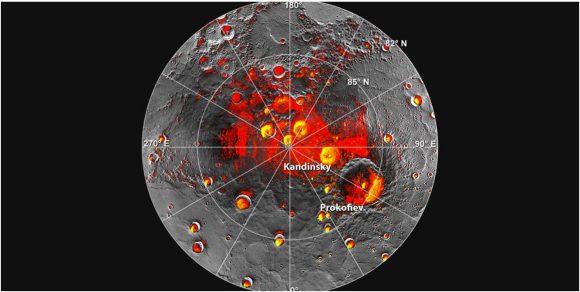

The term “the Universe” is derived from the Latin word “universum”, which was used by Roman statesman Cicero and later Roman authors to refer to the world and the cosmos as they knew it. This consisted of the Earth and all living creatures that dwelt therein, as well as the Moon, the Sun, the then-known planets (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn) and the stars.

The term “cosmos” is often used interchangeably with the Universe. It is derived from the Greek word kosmos, which literally means “the world”. Other words commonly used to define the entirety of existence include “Nature” (derived from the Germanic word natur) and the English word “everything”, who’s use can be seen in scientific terminology – i.e. “Theory Of Everything” (TOE).

Today, this term is often to used to refer to all things that exist within the known Universe – the Solar System, the Milky Way, and all known galaxies and superstructures. In the context of modern science, astronomy and astrophysics, it also refers to all spacetime, all forms of energy (i.e. electromagnetic radiation and matter) and the physical laws that bind them.

Origin of the Universe:

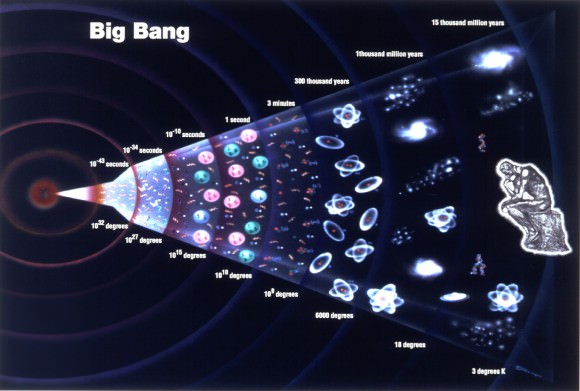

The current scientific consensus is that the Universe expanded from a point of super high matter and energy density roughly 13.8 billion years ago. This theory, known as the Big Bang Theory, is not the only cosmological model for explaining the origins of the Universe and its evolution – for example, there is the Steady State Theory or the Oscillating Universe Theory.

It is, however, the most widely-accepted and popular. This is due to the fact that the Big Bang theory alone is able to explain the origin of all known matter, the laws of physics, and the large scale structure of the Universe. It also accounts for the expansion of the Universe, the existence of the Cosmic Microwave Background, and a broad range of other phenomena.

Working backwards from the current state of the Universe, scientists have theorized that it must have originated at a single point of infinite density and finite time that began to expand. After the initial expansion, the theory maintains that Universe cooled sufficiently to allow for the formation of subatomic particles, and later simple atoms. Giant clouds of these primordial elements later coalesced through gravity to form stars and galaxies.

This all began roughly 13.8 billion years ago, and is thus considered to be the age of the Universe. Through the testing of theoretical principles, experiments involving particle accelerators and high-energy states, and astronomical studies that have observed the deep Universe, scientists have constructed a timeline of events that began with the Big Bang and has led to the current state of cosmic evolution.

However, the earliest times of the Universe – lasting from approximately 10-43 to 10-11 seconds after the Big Bang – are the subject of extensive speculation. Given that the laws of physics as we know them could not have existed at this time, it is difficult to fathom how the Universe could have been governed. What’s more, experiments that can create the kinds of energies involved are in their infancy.

Still, many theories prevail as to what took place in this initial instant in time, many of which are compatible. In accordance with many of these theories, the instant following the Big Bang can be broken down into the following time periods: the Singularity Epoch, the Inflation Epoch, and the Cooling Epoch.

Also known as the Planck Epoch (or Planck Era), the Singularity Epoch was the earliest known period of the Universe. At this time, all matter was condensed on a single point of infinite density and extreme heat. During this period, it is believed that the quantum effects of gravity dominated physical interactions and that no other physical forces were of equal strength to gravitation.

This Planck period of time extends from point 0 to approximately 10-43 seconds, and is so named because it can only be measured in Planck time. Due to the extreme heat and density of matter, the state of the Universe was highly unstable. It thus began to expand and cool, leading to the manifestation of the fundamental forces of physics. From approximately 10-43 second and 10-36, the Universe began to cross transition temperatures.

It is here that the fundamental forces that govern the Universe are believed to have began separating from each other. The first step in this was the force of gravitation separating from gauge forces, which account for strong and weak nuclear forces and electromagnetism. Then, from 10-36 to 10-32 seconds after the Big Bang, the temperature of the Universe was low enough (1028 K) that electromagnetism and weak nuclear force were able to separate as well.

With the creation of the first fundamental forces of the Universe, the Inflation Epoch began, lasting from 10-32 seconds in Planck time to an unknown point. Most cosmological models suggest that the Universe at this point was filled homogeneously with a high-energy density, and that the incredibly high temperatures and pressure gave rise to rapid expansion and cooling.

This began at 10-37 seconds, where the phase transition that caused for the separation of forces also led to a period where the Universe grew exponentially. It was also at this point in time that baryogenesis occurred, which refers to a hypothetical event where temperatures were so high that the random motions of particles occurred at relativistic speeds.

As a result of this, particle–antiparticle pairs of all kinds were being continuously created and destroyed in collisions, which is believed to have led to the predominance of matter over antimatter in the present Universe. After inflation stopped, the Universe consisted of a quark–gluon plasma, as well as all other elementary particles. From this point onward, the Universe began to cool and matter coalesced and formed.

As the Universe continued to decrease in density and temperature, the Cooling Epoch began. This was characterized by the energy of particles decreasing and phase transitions continuing until the fundamental forces of physics and elementary particles changed into their present form. Since particle energies would have dropped to values that can be obtained by particle physics experiments, this period onward is subject to less speculation.

For example, scientists believe that about 10-11 seconds after the Big Bang, particle energies dropped considerably. At about 10-6 seconds, quarks and gluons combined to form baryons such as protons and neutrons, and a small excess of quarks over antiquarks led to a small excess of baryons over antibaryons.

Since temperatures were not high enough to create new proton-antiproton pairs (or neutron-anitneutron pairs), mass annihilation immediately followed, leaving just one in 1010 of the original protons and neutrons and none of their antiparticles. A similar process happened at about 1 second after the Big Bang for electrons and positrons.

After these annihilations, the remaining protons, neutrons and electrons were no longer moving relativistically and the energy density of the Universe was dominated by photons – and to a lesser extent, neutrinos. A few minutes into the expansion, the period known as Big Bang nucleosynthesis also began.

Thanks to temperatures dropping to 1 billion kelvin and energy densities dropping to about the equivalent of air, neutrons and protons began to combine to form the Universe’s first deuterium (a stable isotope of hydrogen) and helium atoms. However, most of the Universe’s protons remained uncombined as hydrogen nuclei.

After about 379,000 years, electrons combined with these nuclei to form atoms (again, mostly hydrogen), while the radiation decoupled from matter and continued to expand through space, largely unimpeded. This radiation is now known to be what constitutes the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), which today is the oldest light in the Universe.

As the CMB expanded, it gradually lost density and energy, and is currently estimated to have a temperature of 2.7260 ± 0.0013 K (-270.424 °C/ -454.763 °F ) and an energy density of 0.25 eV/cm3 (or 4.005×10-14 J/m3; 400–500 photons/cm3). The CMB can be seen in all directions at a distance of roughly 13.8 billion light years, but estimates of its actual distance place it at about 46 billion light years from the center of the Universe.

Evolution of the Universe:

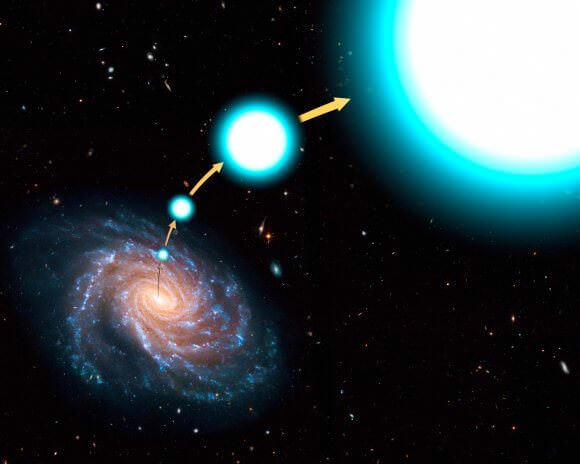

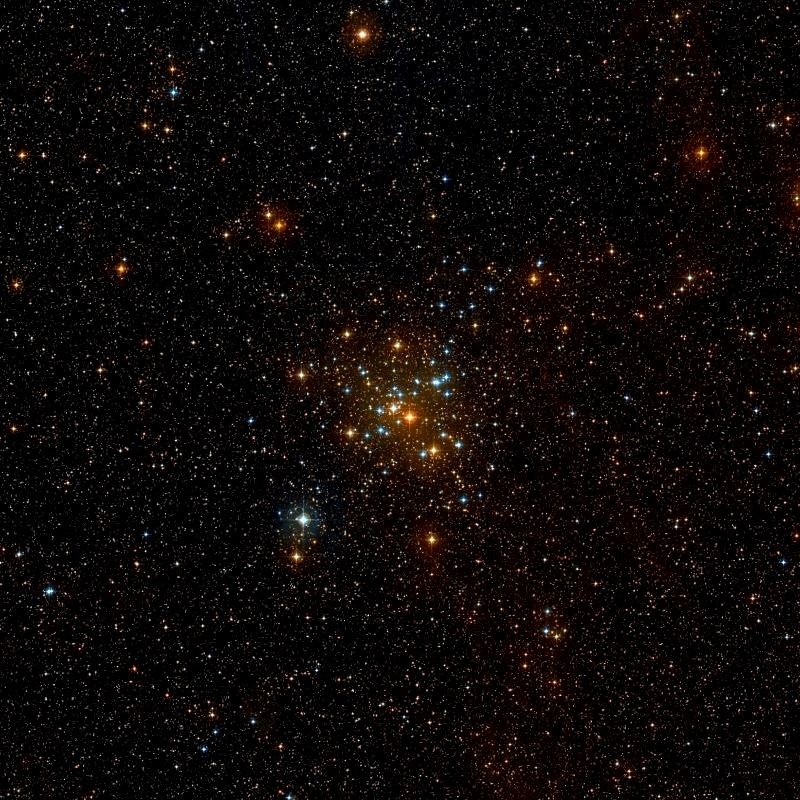

Over the course of the several billion years that followed, the slightly denser regions of the Universe’s matter (which was almost uniformly distributed) began to become gravitationally attracted to each other. They therefore grew even denser, forming gas clouds, stars, galaxies, and the other astronomical structures that we regularly observe today.

This is what is known as the Structure Epoch, since it was during this time that the modern Universe began to take shape. This consisted of visible matter distributed in structures of various sizes (i.e. stars and planets to galaxies, galaxy clusters, and super clusters) where matter is concentrated, and which are separated by enormous gulfs containing few galaxies.

The details of this process depend on the amount and type of matter in the Universe. Cold dark matter, warm dark matter, hot dark matter, and baryonic matter are the four suggested types. However, the Lambda-Cold Dark Matter model (Lambda-CDM), in which the dark matter particles moved slowly compared to the speed of light, is the considered to be the standard model of Big Bang cosmology, as it best fits the available data.

In this model, cold dark matter is estimated to make up about 23% of the matter/energy of the Universe, while baryonic matter makes up about 4.6%. The Lambda refers to the Cosmological Constant, a theory originally proposed by Albert Einstein that attempted to show that the balance of mass-energy in the Universe remains static.

In this case, it is associated with dark energy, which served to accelerate the expansion of the Universe and keep its large-scale structure largely uniform. The existence of dark energy is based on multiple lines of evidence, all of which indicate that the Universe is permeated by it. Based on observations, it is estimated that 73% of the Universe is made up of this energy.

During the earliest phases of the Universe, when all of the baryonic matter was more closely space together, gravity predominated. However, after billions of years of expansion, the growing abundance of dark energy led it to begin dominating interactions between galaxies. This triggered an acceleration, which is known as the Cosmic Acceleration Epoch.

When this period began is subject to debate, but it is estimated to have began roughly 8.8 billion years after the Big Bang (5 billion years ago). Cosmologists rely on both quantum mechanics and Einstein’s General Relativity to describe the process of cosmic evolution that took place during this period and any time after the Inflationary Epoch.

Through a rigorous process of observations and modeling, scientists have determined that this evolutionary period does accord with Einstein’s field equations, though the true nature of dark energy remains illusive. What’s more, there are no well-supported models that are capable of determining what took place in the Universe prior to the period predating 10-15 seconds after the Big Bang.

However, ongoing experiments using CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC) seek to recreate the energy conditions that would have existed during the Big Bang, which is also expected to reveal physics that go beyond the realm of the Standard Model.

Any breakthroughs in this area will likely lead to a unified theory of quantum gravitation, where scientists will finally be able to understand how gravity interacts with the three other fundamental forces of the physics – electromagnetism, weak nuclear force and strong nuclear force. This, in turn, will also help us to understand what truly happened during the earliest epochs of the Universe.

Structure of the Universe:

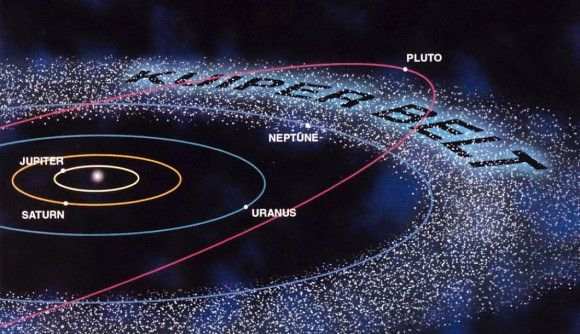

The actual size, shape and large-scale structure of the Universe has been the subject of ongoing research. Whereas the oldest light in the Universe that can be observed is 13.8 billion light years away (the CMB), this is not the actual extent of the Universe. Given that the Universe has been in a state of expansion for billion of years, and at velocities that exceed the speed of light, the actual boundary extends far beyond what we can see.

Our current cosmological models indicate that the Universe measures some 91 billion light years (28 billion parsecs) in diameter. In other words, the observable Universe extends outwards from our Solar System to a distance of roughly 46 billion light years in all directions. However, given that the edge of the Universe is not observable, it is not yet clear whether the Universe actually has an edge. For all we know, it goes on forever!

Within the observable Universe, matter is distributed in a highly structured fashion. Within galaxies, this consists of large concentrations – i.e. planets, stars, and nebulas – interspersed with large areas of empty space (i.e. interplanetary space and the interstellar medium).

Things are much the same at larger scales, with galaxies being separated by volumes of space filled with gas and dust. At the largest scale, where galaxy clusters and superclusters exist, you have a wispy network of large-scale structures consisting of dense filaments of matter and gigantic cosmic voids.

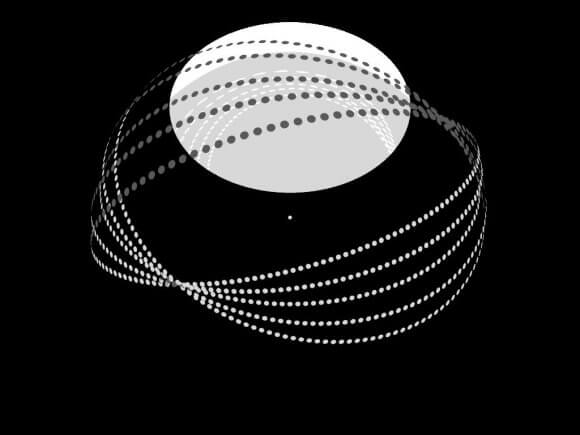

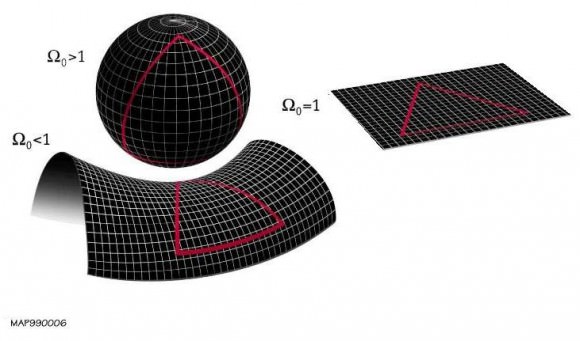

In terms of its shape, spacetime may exist in one of three possible configurations – positively-curved, negatively-curved and flat. These possibilities are based on the existence of at least four dimensions of space-time (an x-coordinate, a y-coordinate, a z-coordinate, and time), and depend upon the nature of cosmic expansion and whether or not the Universe is finite or infinite.

A positively-curved (or closed) Universe would resemble a four-dimensional sphere that would be finite in space and with no discernible edge. A negatively-curved (or open) Universe would look like a four-dimensional “saddle” and would have no boundaries in space or time.

In the former scenario, the Universe would have to stop expanding due to an overabundance of energy. In the latter, it would contain too little energy to ever stop expanding. In the third and final scenario – a flat Universe – a critical amount of energy would exist and its expansion woudl only halt after an infinite amount of time.

Fate of the Universe:

Hypothesizing that the Universe had a starting point naturally gives rise to questions about a possible end point. If the Universe began as a tiny point of infinite density that started to expand, does that mean it will continue to expand indefinitely? Or will it one day run out of expansive force, and begin retreating inward until all matter crunches back into a tiny ball?

Answering this question has been a major focus of cosmologists ever since the debate about which model of the Universe was the correct one began. With the acceptance of the Big Bang Theory, but prior to the observation of dark energy in the 1990s, cosmologists had come to agree on two scenarios as being the most likely outcomes for our Universe.

In the first, commonly known as the “Big Crunch” scenario, the Universe will reach a maximum size and then begin to collapse in on itself. This will only be possible if the mass density of the Universe is greater than the critical density. In other words, as long as the density of matter remains at or above a certain value (1-3 ×10-26 kg of matter per m³), the Universe will eventually contract.

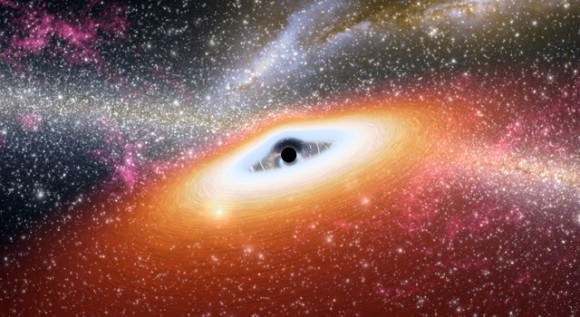

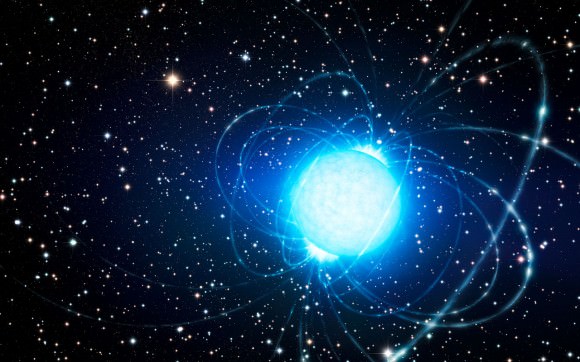

Alternatively, if the density in the Universe were equal to or below the critical density, the expansion would slow down but never stop. In this scenario, known as the “Big Freeze”, the Universe would go on until star formation eventually ceased with the consumption of all the interstellar gas in each galaxy. Meanwhile, all existing stars would burn out and become white dwarfs, neutron stars, and black holes.

Very gradually, collisions between these black holes would result in mass accumulating into larger and larger black holes. The average temperature of the Universe would approach absolute zero, and black holes would evaporate after emitting the last of their Hawking radiation. Finally, the entropy of the Universe would increase to the point where no organized form of energy could be extracted from it (a scenarios known as “heat death”).

Modern observations, which include the existence of dark energy and its influence on cosmic expansion, have led to the conclusion that more and more of the currently visible Universe will pass beyond our event horizon (i.e. the CMB, the edge of what we can see) and become invisible to us. The eventual result of this is not currently known, but “heat death” is considered a likely end point in this scenario too.

Other explanations of dark energy, called phantom energy theories, suggest that ultimately galaxy clusters, stars, planets, atoms, nuclei, and matter itself will be torn apart by the ever-increasing expansion. This scenario is known as the “Big Rip”, in which the expansion of the Universe itself will eventually be its undoing.

History of Study:

Strictly speaking, human beings have been contemplating and studying the nature of the Universe since prehistoric times. As such, the earliest accounts of how the Universe came to be were mythological in nature and passed down orally from one generation to the next. In these stories, the world, space, time, and all life began with a creation event, where a God or Gods were responsible for creating everything.

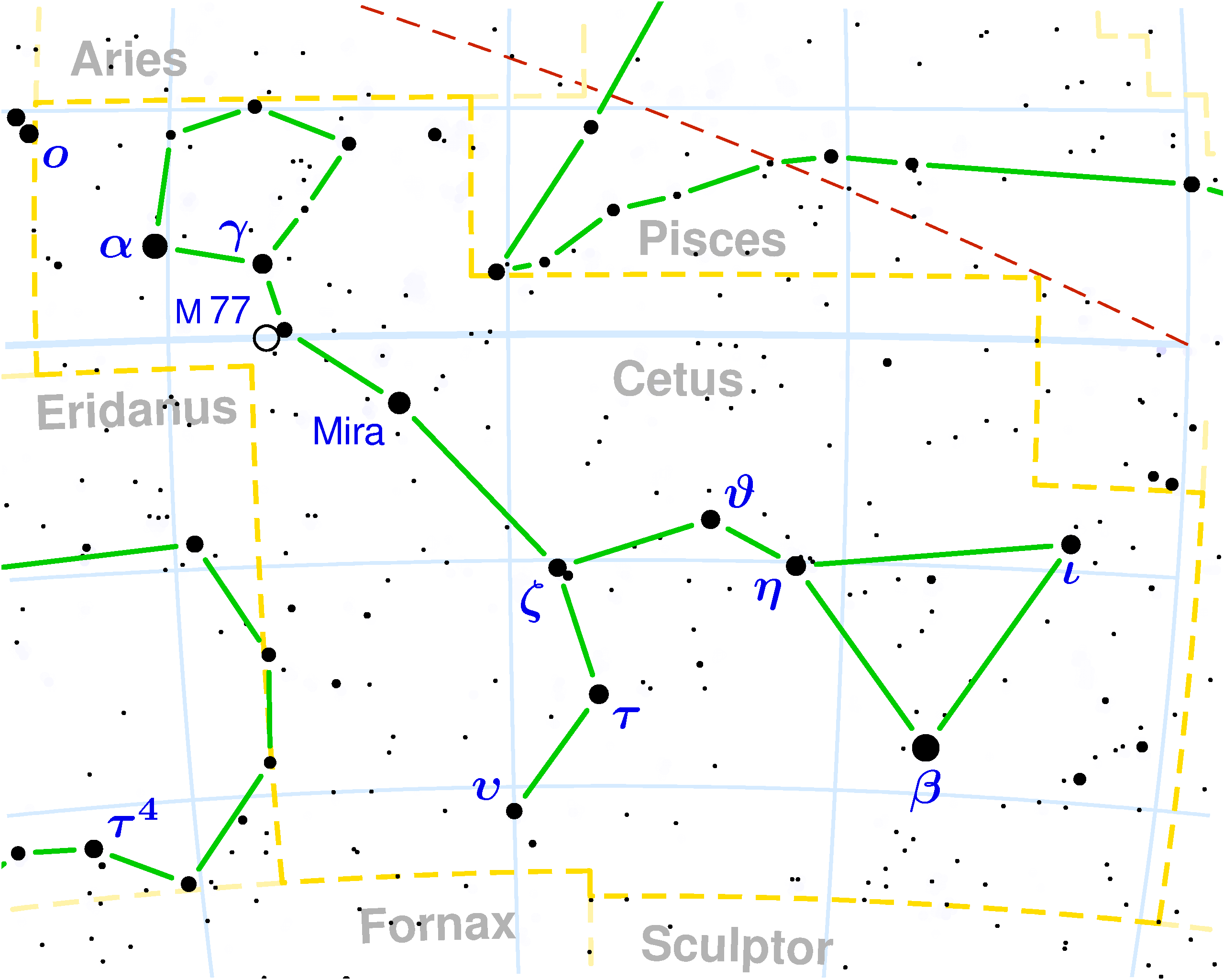

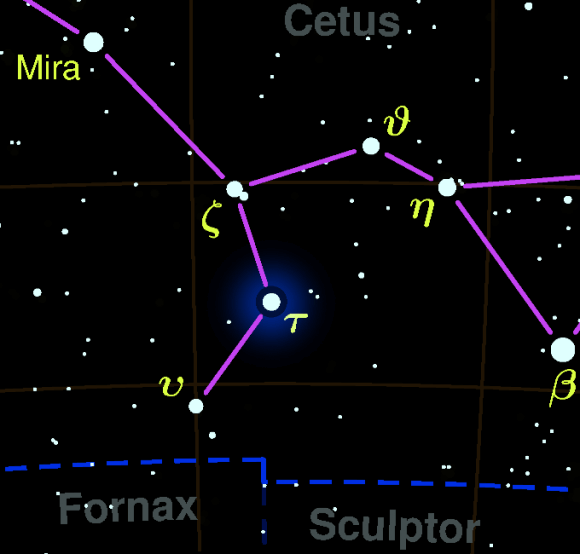

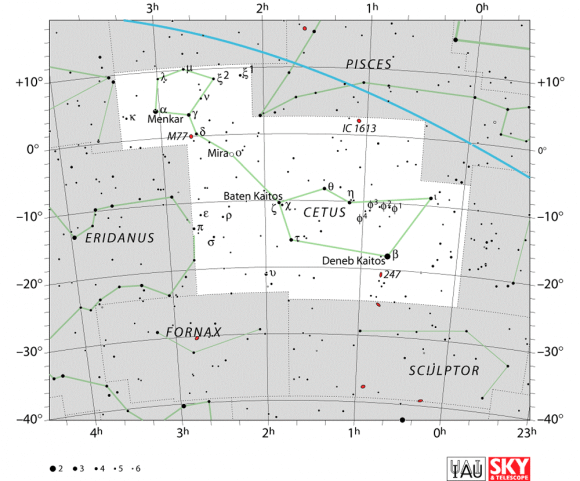

Astronomy also began to emerge as a field of study by the time of the Ancient Babylonians. Systems of constellations and astrological calendars prepared by Babylonian scholars as early as the 2nd millennium BCE would go on to inform the cosmological and astrological traditions of cultures for thousands of years to come.

By Classical Antiquity, the notion of a Universe that was dictated by physical laws began to emerge. Between Greek and Indian scholars, explanations for creation began to become philosophical in nature, emphasizing cause and effect rather than divine agency. The earliest examples include Thales and Anaximander, two pre-Socratic Greek scholars who argued that everything was born of a primordial form of matter.

By the 5th century BCE, pre-Socratic philosopher Empedocles became the first western scholar to propose a Universe composed of four elements – earth, air, water and fire. This philosophy became very popular in western circles, and was similar to the Chinese system of five elements – metal, wood, water, fire, and earth – that emerged around the same time.

It was not until Democritus, the 5th/4th century BCE Greek philosopher, that a Universe composed of indivisible particles (atoms) was proposed. The Indian philosopher Kanada (who lived in the 6th or 2nd century BCE) took this philosophy further by proposing that light and heat were the same substance in different form. The 5th century CE Buddhist philosopher Dignana took this even further, proposing that all matter was made up of energy.

The notion of finite time was also a key feature of the Abrahamic religions – Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Perhaps inspired by the Zoroastrian concept of the Day of Judgement, the belief that the Universe had a beginning and end would go on to inform western concepts of cosmology even to the present day.

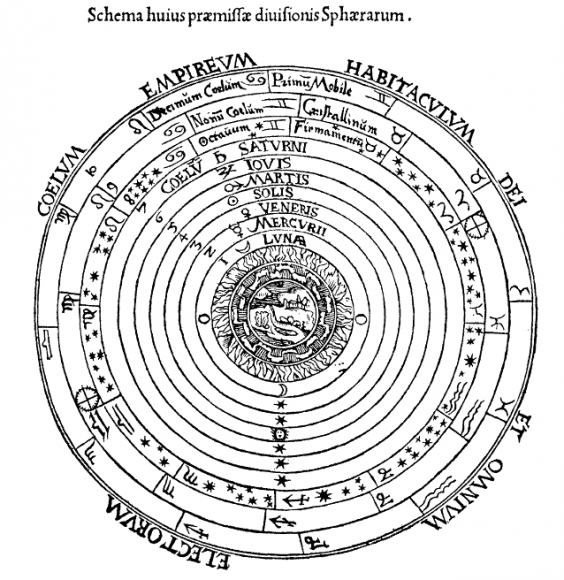

Between the 2nd millennium BCE and the 2nd century CE, astronomy and astrology continued to develop and evolve. In addition to monitoring the proper motions of the planets and the movement of the constellations through the Zodiac, Greek astronomers also articulated the geocentric model of the Universe, where the Sun, planets and stars revolve around the Earth.

These traditions are best described in the 2nd century CE mathematical and astronomical treatise, the Almagest, which was written by Greek-Egyptian astronomer Claudius Ptolemaeus (aka. Ptolemy). This treatise and the cosmological model it espoused would be considered canon by medieval European and Islamic scholars for over a thousand years to come.

However, even before the Scientific Revolution (ca. 16th to 18th centuries), there were astronomers who proposed a heliocentric model of the Universe – where the Earth, planets and stars revolved around the Sun. These included Greek astronomer Aristarchus of Samos (ca. 310 – 230 BCE), and Hellenistic astronomer and philosopher Seleucus of Seleucia (190 – 150 BCE).

During the Middle Ages, Indian, Persian and Arabic philosophers and scholars maintained and expanded on Classical astronomy. In addition to keeping Ptolemaic and non-Aristotelian ideas alive, they also proposed revolutionary ideas like the rotation of the Earth. Some scholars – such as Indian astronomer Aryabhata and Persian astronomers Albumasar and Al-Sijzi – even advanced versions of a heliocentric Universe.

By the 16th century, Nicolaus Copernicus proposed the most complete concept of a heliocentric Universe by resolving lingering mathematical problems with the theory. His ideas were first expressed in the 40-page manuscript titled Commentariolus (“Little Commentary”), which described a heliocentric model based on seven general principles. These seven principles stated that:

- Celestial bodies do not all revolve around a single point

- The center of Earth is the center of the lunar sphere—the orbit of the moon around Earth; all the spheres rotate around the Sun, which is near the center of the Universe

- The distance between Earth and the Sun is an insignificant fraction of the distance from Earth and Sun to the stars, so parallax is not observed in the stars

- The stars are immovable – their apparent daily motion is caused by the daily rotation of Earth

- Earth is moved in a sphere around the Sun, causing the apparent annual migration of the Sun

- Earth has more than one motion

- Earth’s orbital motion around the Sun causes the seeming reverse in direction of the motions of the planets.

A more comprehensive treatment of his ideas was released in 1532, when Copernicus completed his magnum opus – De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres). In it, he advanced his seven major arguments, but in more detailed form and with detailed computations to back them up. Due to fears of persecution and backlash, this volume was not released until his death in 1542.

His ideas would be further refined by 16th/17th century mathematicians, astronomer and inventor Galileo Galilei. Using a telescope of his own creation, Galileo would make recorded observations of the Moon, the Sun, and Jupiter which demonstrated flaws in the geocentric model of the Universe while also showcasing the internal consistency of the Copernican model.

His observations were published in several different volumes throughout the early 17th century. His observations of the cratered surface of the Moon and his observations of Jupiter and its largest moons were detailed in 1610 with his Sidereus Nuncius (The Starry Messenger) while his observations were sunspots were described in On the Spots Observed in the Sun (1610).

Galileo also recorded his observations about the Milky Way in the Starry Messenger, which was previously believed to be nebulous. Instead, Galileo found that it was a multitude of stars packed so densely together that it appeared from a distance to look like clouds, but which were actually stars that were much farther away than previously thought.

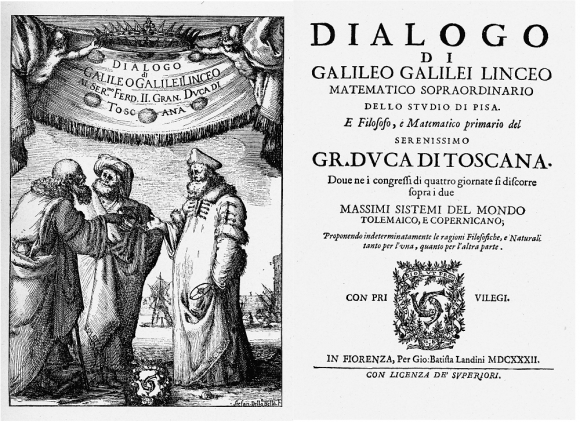

In 1632, Galileo finally addressed the “Great Debate” in his treatise Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo (Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems), in which he advocated the heliocentric model over the geocentric. Using his own telescopic observations, modern physics and rigorous logic, Galileo’s arguments effectively undermined the basis of Aristotle’s and Ptolemy’s system for a growing and receptive audience.

Johannes Kepler advanced the model further with his theory of the elliptical orbits of the planets. Combined with accurate tables that predicted the positions of the planets, the Copernican model was effectively proven. From the middle of the seventeenth century onward, there were few astronomers who were not Copernicans.

The next great contribution came from Sir Isaac Newton (1642/43 – 1727), who’s work with Kepler’s Laws of Planetary Motion led him to develop his theory of Universal Gravitation. In 1687, he published his famous treatise Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (“Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy”), which detailed his Three Laws of Motion. These laws stated that:

- When viewed in an inertial reference frame, an object either remains at rest or continues to move at a constant velocity, unless acted upon by an external force.

- The vector sum of the external forces (F) on an object is equal to the mass (m) of that object multiplied by the acceleration vector (a) of the object. In mathematical form, this is expressed as: F=ma

- When one body exerts a force on a second body, the second body simultaneously exerts a force equal in magnitude and opposite in direction on the first body.

Together, these laws described the relationship between any object, the forces acting upon it, and the resulting motion, thus laying the foundation for classical mechanics. The laws also allowed Newton to calculate the mass of each planet, calculate the flattening of the Earth at the poles and the bulge at the equator, and how the gravitational pull of the Sun and Moon create the Earth’s tides.

His calculus-like method of geometrical analysis was also able to account for the speed of sound in air (based on Boyle’s Law), the precession of the equinoxes – which he showed were a result of the Moon’s gravitational attraction to the Earth – and determine the orbits of the comets. This volume would have a profound effect on the sciences, with its principles remaining canon for the following 200 years.

Another major discovery took place in 1755, when Immanuel Kant proposed that the Milky Way was a large collection of stars held together by mutual gravity. Just like the Solar System, this collection of stars would be rotating and flattened out as a disk, with the Solar System embedded within it.

Astronomer William Herschel attempted to actually map out the shape of the Milky Way in 1785, but he didn’t realize that large portions of the galaxy are obscured by gas and dust, which hides its true shape. The next great leap in the study of the Universe and the laws that govern it did not come until the 20th century, with the development of Einstein’s theories of Special and General Relativity.

Einstein’s groundbreaking theories about space and time (summed up simply as E=mc²) were in part the result of his attempts to resolve Newton’s laws of mechanics with the laws of electromagnetism (as characterized by Maxwell’s equations and the Lorentz force law). Eventually, Einstein would resolve the inconsistency between these two fields by proposing Special Relativity in his 1905 paper, “On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies“.

Basically, this theory stated that the speed of light is the same in all inertial reference frames. This broke with the previously-held consensus that light traveling through a moving medium would be dragged along by that medium, which meant that the speed of the light is the sum of its speed through a medium plus the speed of that medium. This theory led to multiple issues that proved insurmountable prior to Einstein’s theory.

Special Relativity not only reconciled Maxwell’s equations for electricity and magnetism with the laws of mechanics, but also simplified the mathematical calculations by doing away with extraneous explanations used by other scientists. It also made the existence of a medium entirely superfluous, accorded with the directly observed speed of light, and accounted for the observed aberrations.

Between 1907 and 1911, Einstein began considering how Special Relativity could be applied to gravity fields – what would come to be known as the Theory of General Relativity. This culminated in 1911 with the publications of “On the Influence of Gravitation on the Propagation of Light“, in which he predicted that time is relative to the observer and dependent on their position within a gravity field.

He also advanced what is known as the Equivalence Principle, which states that gravitational mass is identical to inertial mass. Einstein also predicted the phenomenon of gravitational time dilation – where two observers situated at varying distances from a gravitating mass perceive a difference in the amount of time between two events. Another major outgrowth of his theories were the existence of Black Holes and an expanding Universe.

In 1915, a few months after Einstein had published his Theory of General Relativity, German physicist and astronomer Karl Schwarzschild found a solution to the Einstein field equations that described the gravitational field of a point and spherical mass. This solution, now called the Schwarzschild radius, describes a point where the mass of a sphere is so compressed that the escape velocity from the surface would equal the speed of light.

In 1931, Indian-American astrophysicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar calculated, using Special Relativity, that a non-rotating body of electron-degenerate matter above a certain limiting mass would collapse in on itself. In 1939, Robert Oppenheimer and others concurred with Chandrasekhar’s analysis, claiming that neutron stars above a prescribed limit would collapse into black holes.

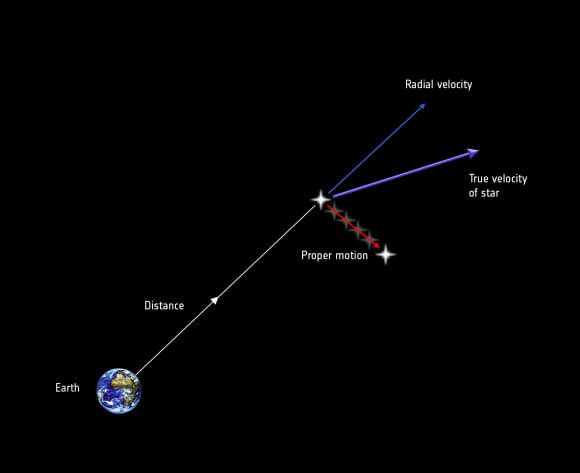

Another consequence of General Relativity was the prediction that the Universe was either in a state of expansion or contraction. In 1929, Edwin Hubble confirmed that the former was the case. At the time, this appeared to disprove Einstein’s theory of a Cosmological Constant, which was a force which “held back gravity” to ensure that the distribution of matter in the Universe remained uniform over time.

To this, Edwin Hubble demonstrated using redshift measurements that galaxies were moving away from the Milky Way. What’s more, he showed that the galaxies that were farther from Earth appeared to be receding faster – a phenomena that would come to be known as Hubble’s Law. Hubble attempted to constrain the value of the expansion factor – which he estimated at 500 km/sec per Megaparsec of space (which has since been revised).

And then in 1931, Georges Lemaitre, a Belgian physicist and Roman Catholic priest, articulated an idea that would give rise to the Big Bang Theory. After confirming independently that the Universe was in a state of expansion, he suggested that the current expansion of the Universe meant that the father back in time one went, the smaller the Universe would be.

In other words, at some point in the past, the entire mass of the Universe would have been concentrated on a single point. These discoveries triggered a debate between physicists throughout the 1920s and 30s, with the majority advocating that the Universe was in a steady state (i.e. the Steady State Theory). In this model, new matter is continuously created as the Universe expands, thus preserving the uniformity and density of matter over time.

After World War II, the debate came to a head between proponents of the Steady State Model and proponents of the Big Bang Theory – which was growing in popularity. Eventually, the observational evidence began to favor the Big Bang over the Steady State, which included the discovery and confirmation of the CMB in 1965. Since that time, astronomers and cosmologists have sought to resolve theoretical problems arising from this model.

In the 1960s, for example, Dark Matter (originally proposed in 1932 by Jan Oort) was proposed as an explanation for the apparent “missing mass” of the Universe. In addition, papers submitted by Stephen Hawking and other physicists showed that singularities were an inevitable initial condition of general relativity and a Big Bang model of cosmology.

In 1981, physicist Alan Guth theorized a period of rapid cosmic expansion (aka. the “Inflation” Epoch) that resolved other theoretical problems. The 1990s also saw the rise of Dark Energy as an attempt to resolve outstanding issues in cosmology. In addition to providing an explanation as to the Universe’s missing mass (along with Dark Matter) it also provided an explanation as to why the Universe is still accelerating, and offered a resolution to Einstein’s Cosmological Constant.

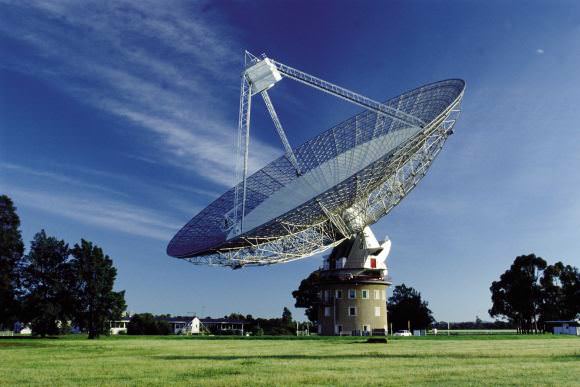

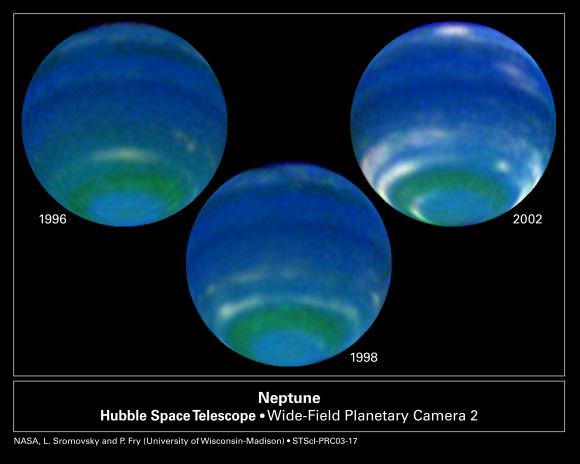

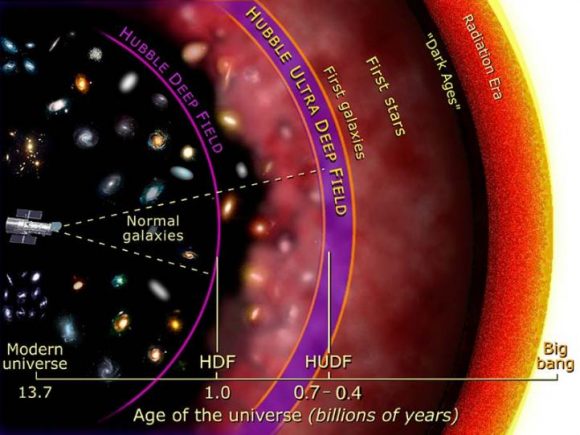

Significant progress has been made in our study of the Universe thanks to advances in telescopes, satellites, and computer simulations. These have allowed astronomers and cosmologists to see farther into the Universe (and hence, farther back in time). This has in turn helped them to gain a better understanding of its true age, and make more precise calculations of its matter-energy density.

The introduction of space telescopes – such as the Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE), the Hubble Space Telescope, Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) and the Planck Observatory – has also been of immeasurable value. These have not only allowed for deeper views of the cosmos, but allowed astronomers to test theoretical models to observations.

For example, in June of 2016, NASA announced findings that indicate that the Universe is expanding even faster than previously thought. Based on new data provided by the Hubble Space Telescope (which was then compared to data from the WMAP and the Planck Observatory) it appeared that the Hubble Constant was 5% to 9% greater than expected.

Next-generation telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and ground-based telescopes like the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) are also expected to allow for additional breakthroughs in our understanding of the Universe in the coming years and decades.

Without a doubt, the Universe is beyond the reckoning of our minds. Our best estimates say hat it is unfathomably vast, but for all we know, it could very well extend to infinity. What’s more, its age in almost impossible to contemplate in strictly human terms. In the end, our understanding of it is nothing less than the result of thousands of years of constant and progressive study.

And in spite of that, we’ve only really begun to scratch the surface of the grand enigma that it is the Universe. Perhaps some day we will be able to see to the edge of it (assuming it has one) and be able to resolve the most fundamental questions about how all things in the Universe interact. Until that time, all we can do is measure what we don’t know by what we do, and keep exploring!

To speed you on your way, here is a list of topics we hope you will enjoy and that will answer your questions. Good luck with your exploration!

Further Reading:

- Age of the Universe

- Atoms in the Universe

- Beginning of the Universe

- Big Crunch

- Big Freeze

- Big Rip

- Center of the Universe

- Cosmology

- Dark Matter

- Density of the Universe

- Expanding Universe

- End of the Universe

- Flat Universe

- Fate of the Universe

- Finite Universe

- How Big is the Universe?

- How Cold is Space?

- How Do We Know Dark Energy Exists?

- How Far can You see in the Universe?

- How Many Atoms are there in the Universe?

- How Many Galaxies are There in the Universe?

- How Many Stars are There in the Universe?

- How Old is the Universe?

- How Will the Universe End?

- Hubble Deep Space

- Hubble’s Law

- Interesting Facts About the Universe

- Infinite Universe

- Is the Universe Finite or Infinite?

- Is Everything in the Universe Expanding?

- Map of the Universe

- Open Universe

- Oscillating Universe Theory

- Parallel Universe

- Quintessence

- Shape of the Universe

- Structure of the Universe

- What are WIMPS?

- What Does the Universe Do When We Are Not Looking?

- What is Entropy?

- What is the Biggest Star in the Universe?

- What is the Biggest Things in the Universe?

- What is the Geocentric Model of the Universe?

- What is the Heliocentric Model of the Universe?

- What is the Multiverse Theory?

- What is the Universe Expanding Into?

- What’s Outside the Universe?

- What Time is it in the Universe?

- What Will We Never See?

- When was the First Light in the Universe?

- Will the Universe Run Out of Energy?

Sources: