Is there life on other planets, somewhere in this enormous Universe? That’s probably the most compelling question we can ask. A lot of space science and space missions are pointed directly at that question.

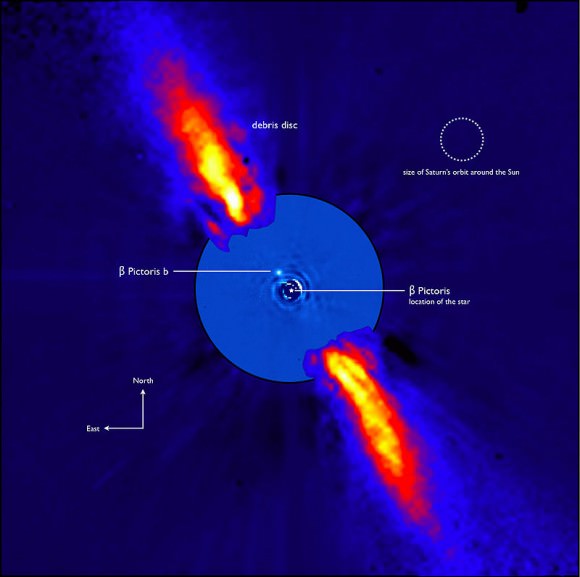

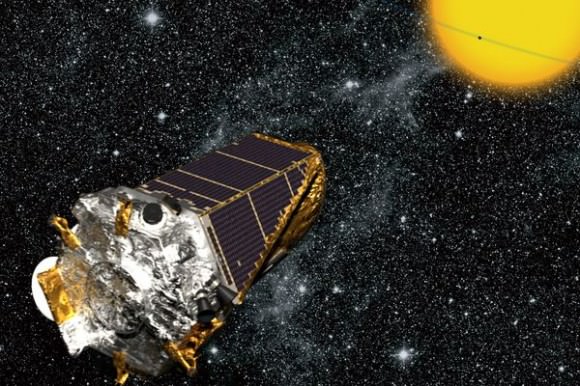

The Kepler mission is designed to find exoplanets, which are planets orbiting other stars. More specifically, its aim is to find planets situated in the habitable zone around their star. And it’s done so. The Kepler mission has found 297 confirmed and candidate planets that are likely in the habitable zone of their star, and it’s only looked at a tiny patch of the sky.

But we don’t know if any of them harbour life, or if Mars ever did, or if anywhere ever did. We just don’t know. But since the question of life elsewhere in the Universe is so compelling, it’s driven people with intellectual curiosity to try and compute the likelihood of life on other planets.

One of the main ways people have tried to understand if life is prevalent in the Universe is through the Drake Equation, named after Dr. Frank Drake. He tried to come up with a way to compute the probability of the existence of other civilizations. The Drake Equation is a mainstay of the conversation around the existence of life in the Universe.

The Drake Equation is a way to calculate the probability of extraterrestrial civilizations in the Milky Way that were technologically advanced to communicate. When it was created in 1961, Drake himself explained that it was really just a way of starting a conversation about extraterrestrial civilizations, rather than a definitive calculation. Still, the equation is the starting point for a lot of conversations.

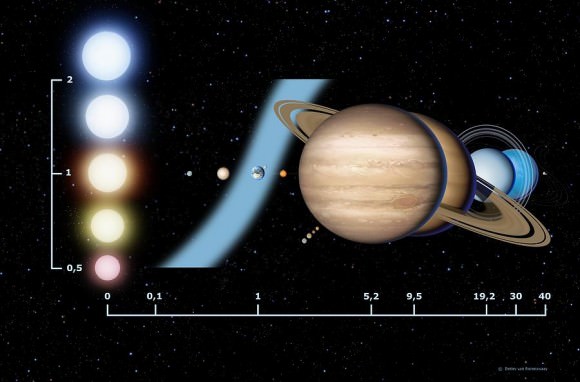

But the problem with the Drake equation, and with all of our attempts to understand the likelihood of life starting on other planets, is that we only have the Earth to go by. It seems like life on Earth started pretty early, and has been around for a long time. With that in mind, people have looked out into the Universe, estimated the number of planets in habitable zones, and concluded that life must be present, and even plentiful, in the Universe.

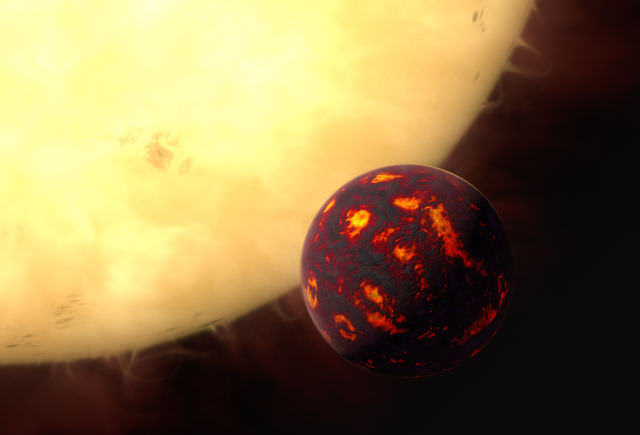

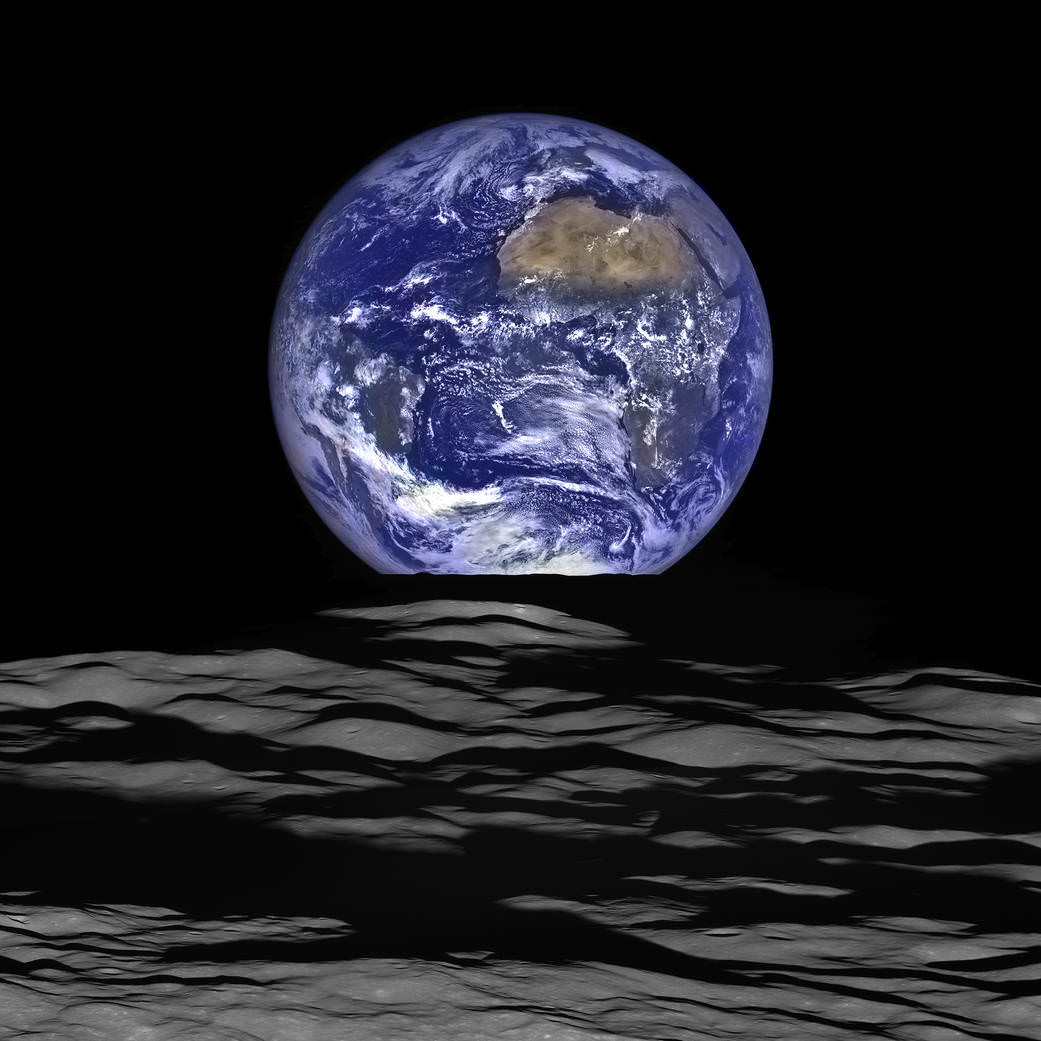

But we really only know two things: First, life on Earth began a few hundred million years after the planet was formed, when it was sufficiently cool and when there was liquid water. The second thing that we know is that a few billions of years after life started, creatures appeared which were sufficiently intelligent enough to wonder about life.

In 2012, two scientists published a paper which reminded us of this fact. David Spiegel, from Princeton University, and Edwin Turner, from the University of Tokyo, conducted what’s called a Bayesian analysis on how our understanding of the early emergence of life on Earth affects our understanding of the existence of life elsewhere.

A Bayesian analysis is a complicated matter for non-specialists, but in this paper it’s used to separate out the influence of data, and the influence of our prior beliefs, when estimating the probability of life on other worlds. What the two researchers concluded is that our prior beliefs about the existence of life elsewhere have a large effect on any probabilistic conclusions we make about life elsewhere. As the authors say in the paper, “Life arose on Earth sometime in the first few hundred million years after the young planet had cooled to the point that it could support water-based organisms on its surface. The early emergence of life on Earth has been taken as evidence that the probability of abiogenesis is high, if starting from young-Earth-like conditions.”

A key part of all this is that life may have had a head start on Earth. Since then, it’s taken about 3.5 billion years for creatures to evolve to the point where they can think about such things. So this is where we find ourselves; looking out into the Universe and searching and wondering. But it’s possible that life may take a lot longer to get going on other worlds. We just don’t know, but many of the guesses have assumed that abiogenesis on Earth is standard for other planets.

What it all boils down to, is that we only have one data point, which is life on Earth. And from that point, we have extrapolated outward, concluding hopefully that life is plentiful, and we will eventually find it. We’re certainly getting better at finding locations that should be suitable for life to arise.

What’s maddening about it all is that we just don’t know. We keep looking and searching, and developing technology to find habitable planets and identify bio-markers for life, but until we actually find life elsewhere, we still only have one data point: Earth. But Earth might be exceptional.

As Spiegel and Turner say in the conclusion of their paper, ” In short, if we should find evidence of life that arose wholly idependently of us – either via astronomical searches that reveal life on another planet or via geological and biological studies that find evidence of life on Earth with a different origin from us – we would have considerably stronger grounds to conclude that life is probably common in our galaxy.”

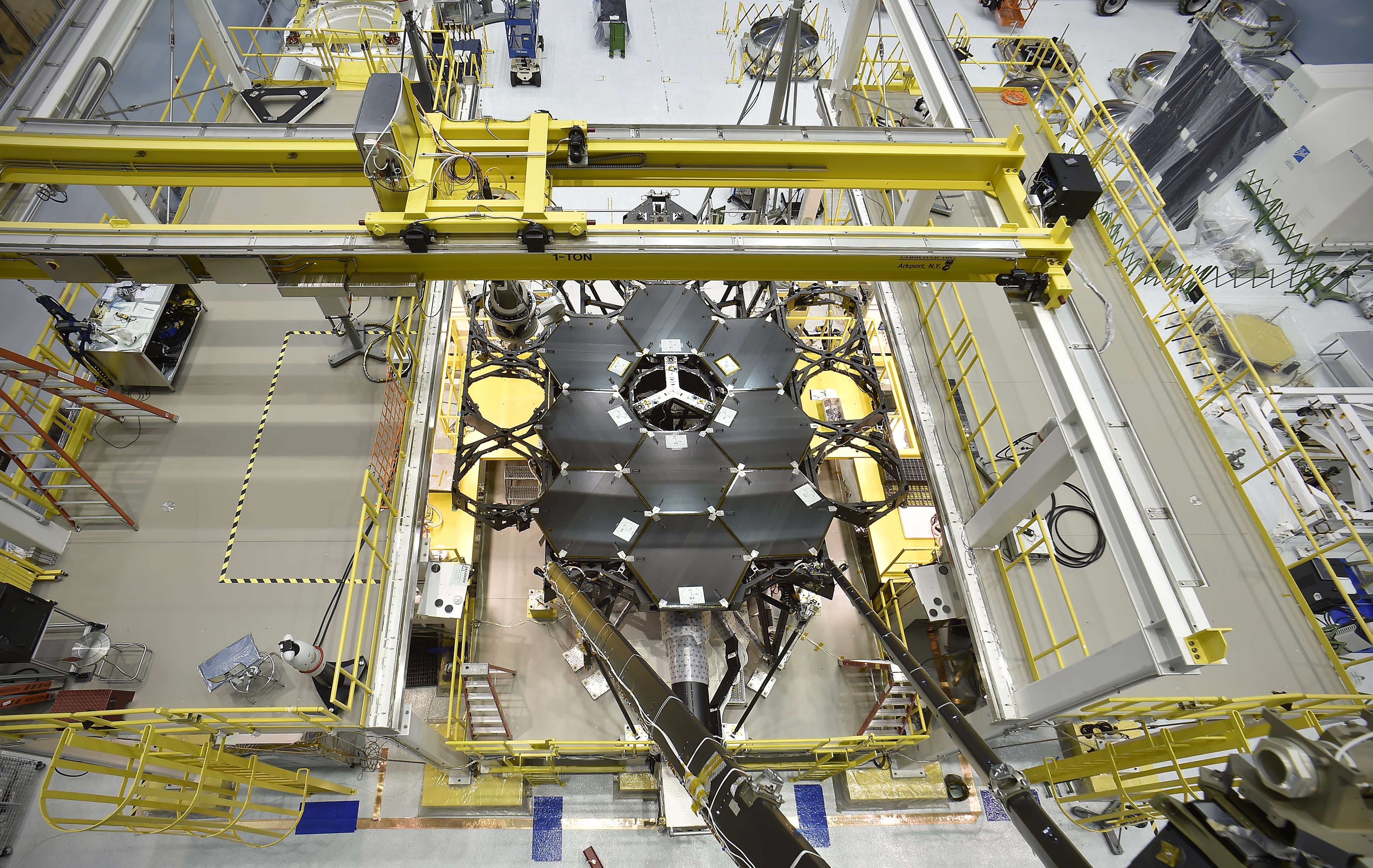

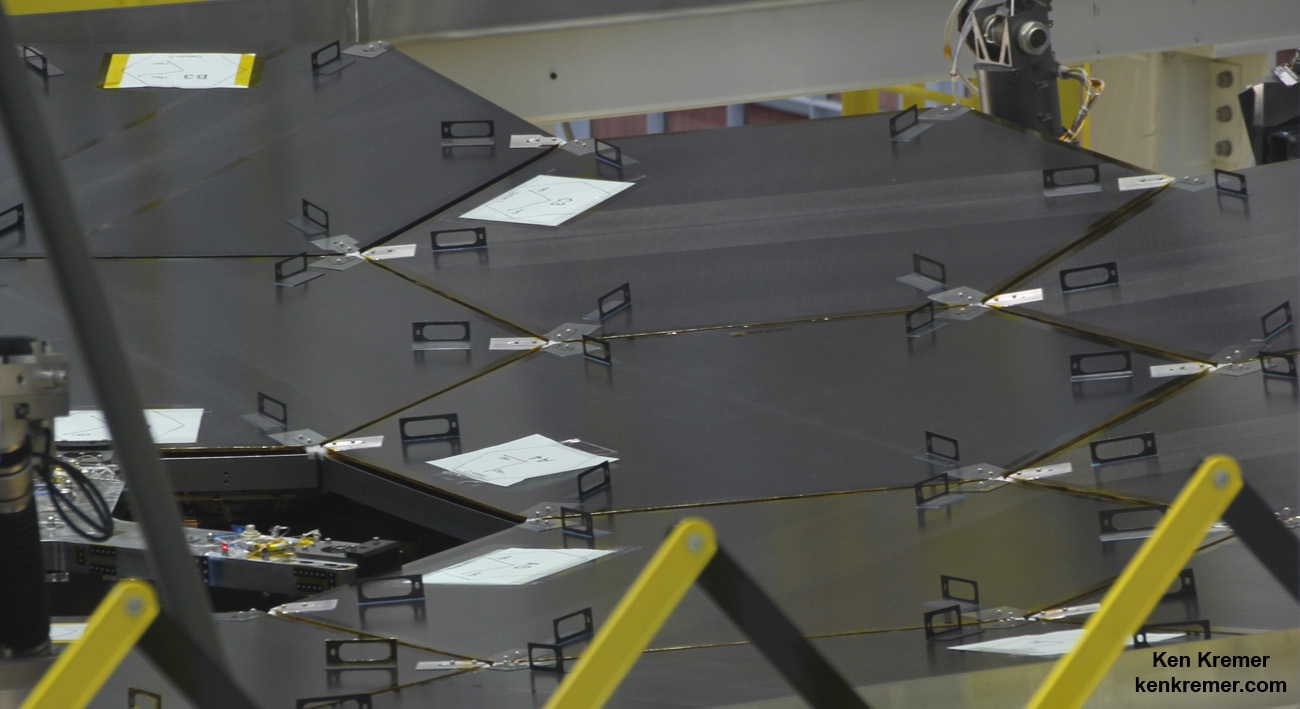

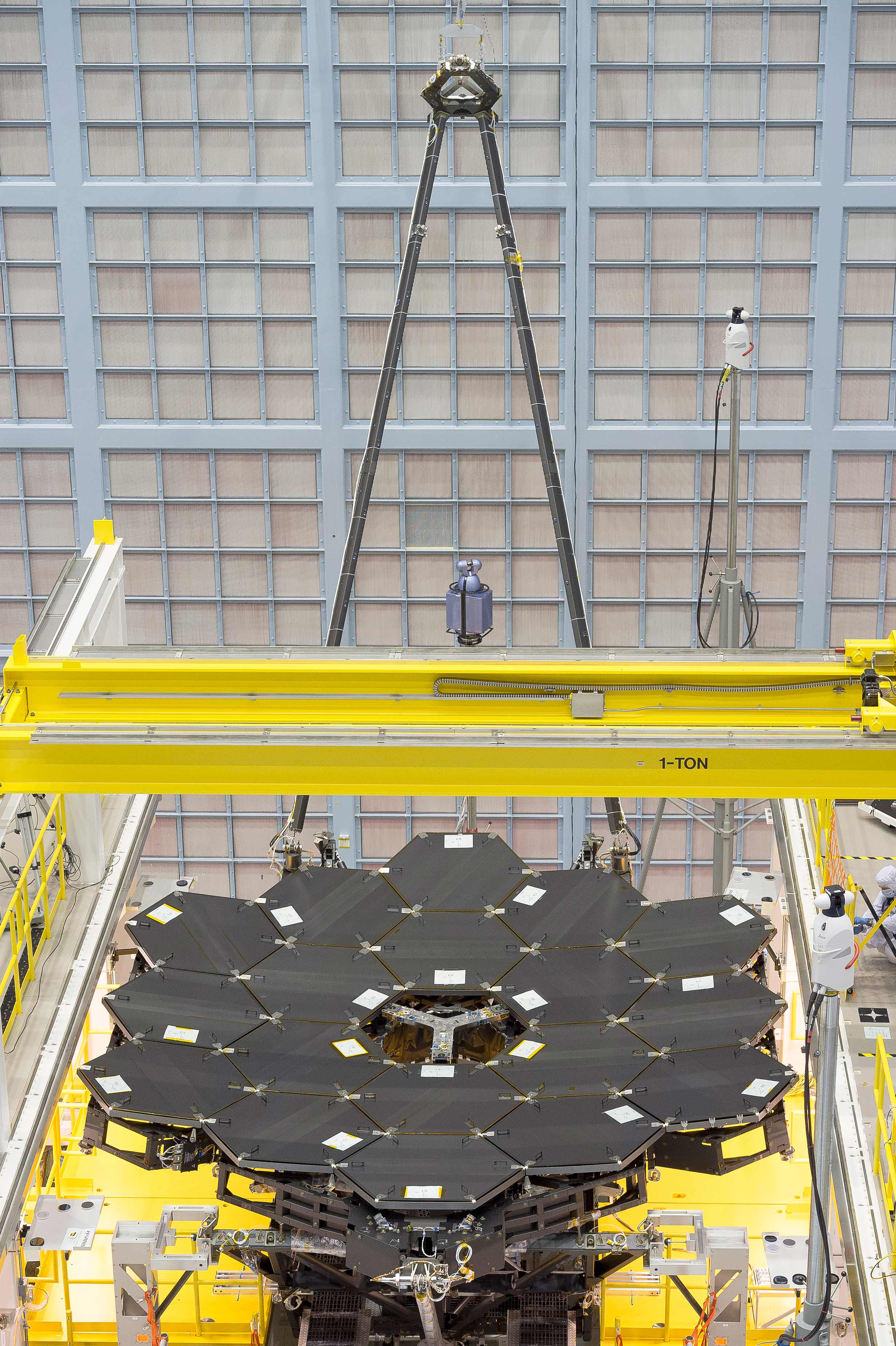

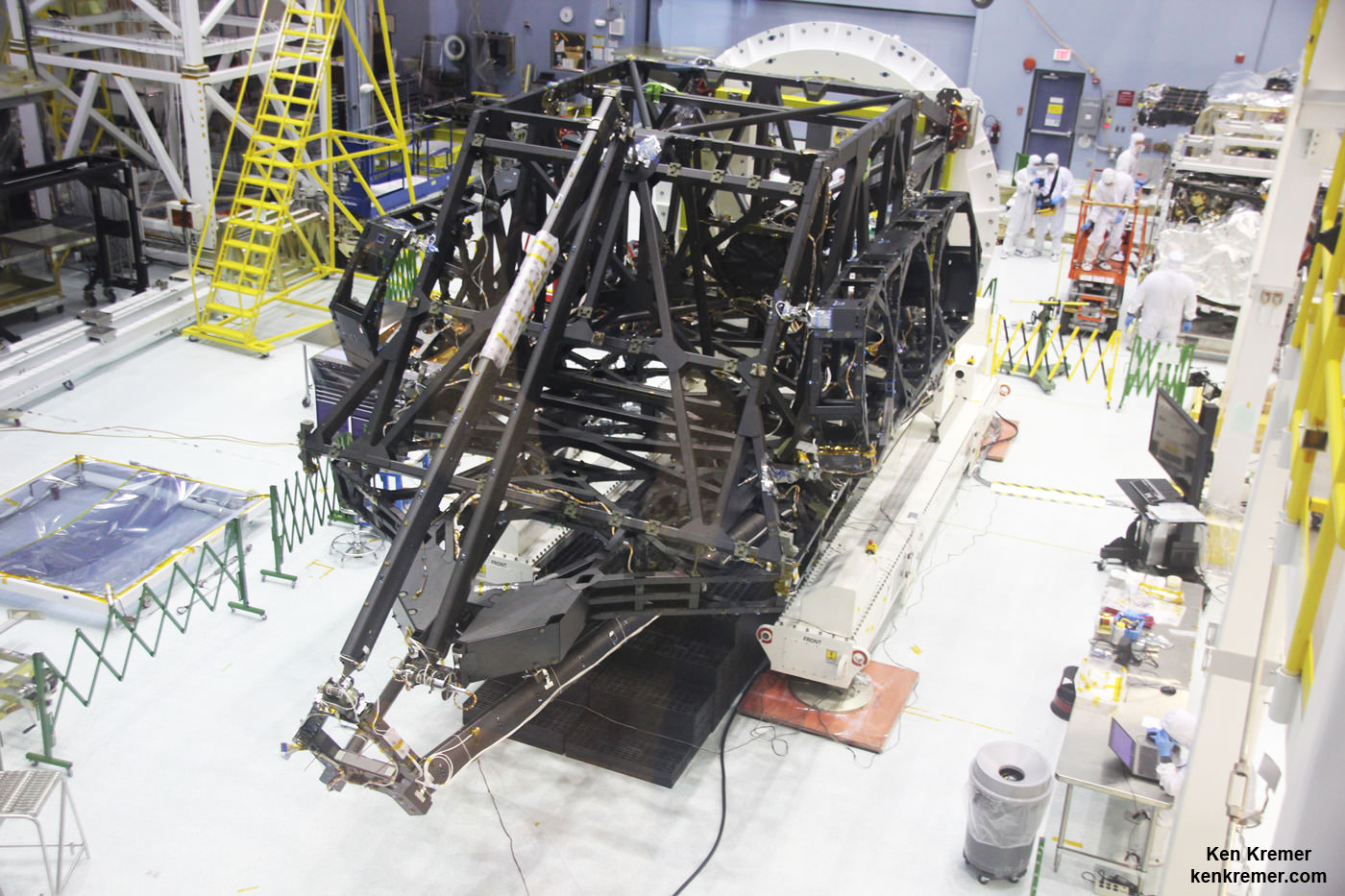

With our growing understanding of Mars, and with missions like the James Webb Space Telescope, we may one day soon have one more data point with which we can refine our probabilistic understanding of other life in the Universe.

Or, there could be a sadder outcome. Maybe life on Earth will perish before we ever find another living microbe on any other world.