[/caption]

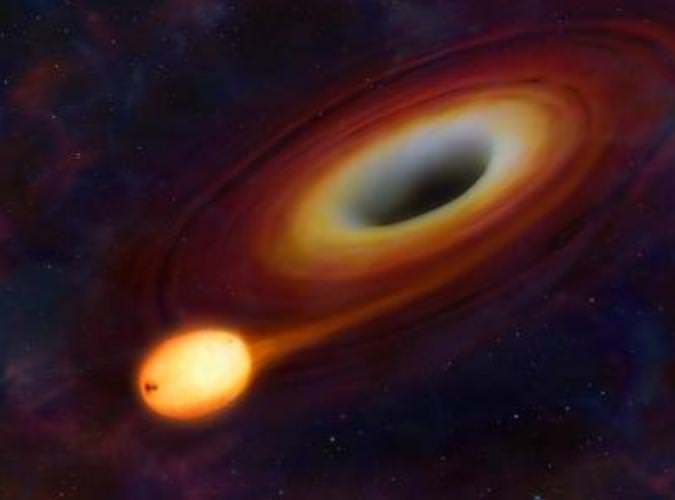

“The world is a vampire, sent to drain… Secret destroyers, hold you up to the flames…” Ah, yes. It’s the biggest vampire of all – the supermassive black hole. In this instance, it’s not any average, garden-variety black hole, but one that’s 300 million times the mass of the Sun and growing. Bullet with butterfly wings? No. This is more a case of butterfly wings with bullets.

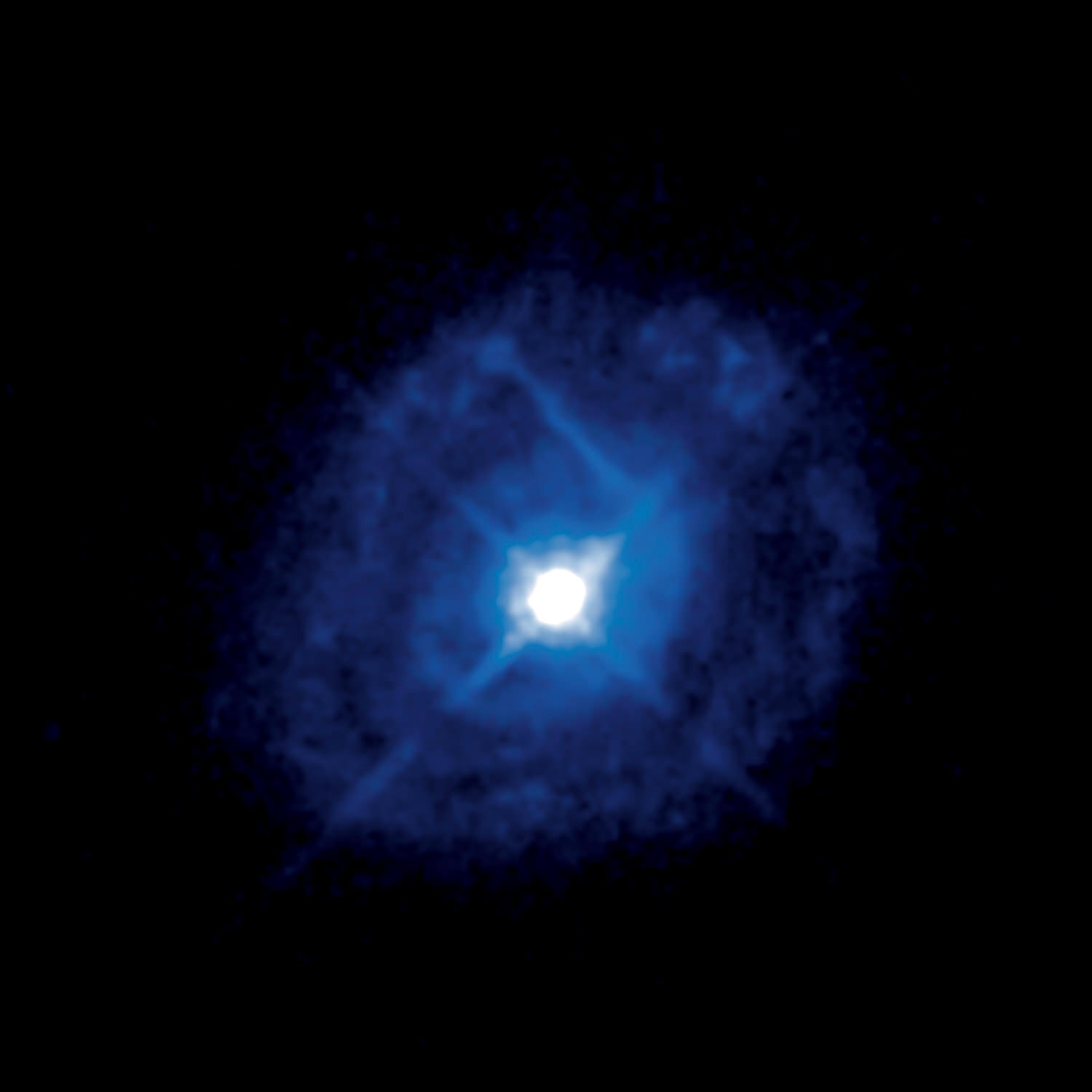

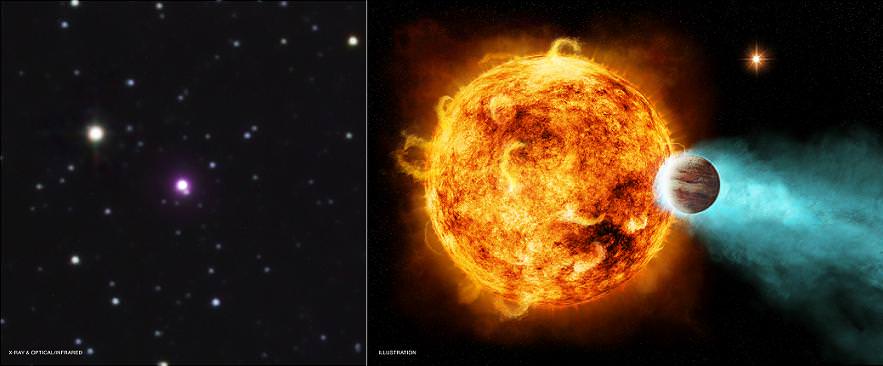

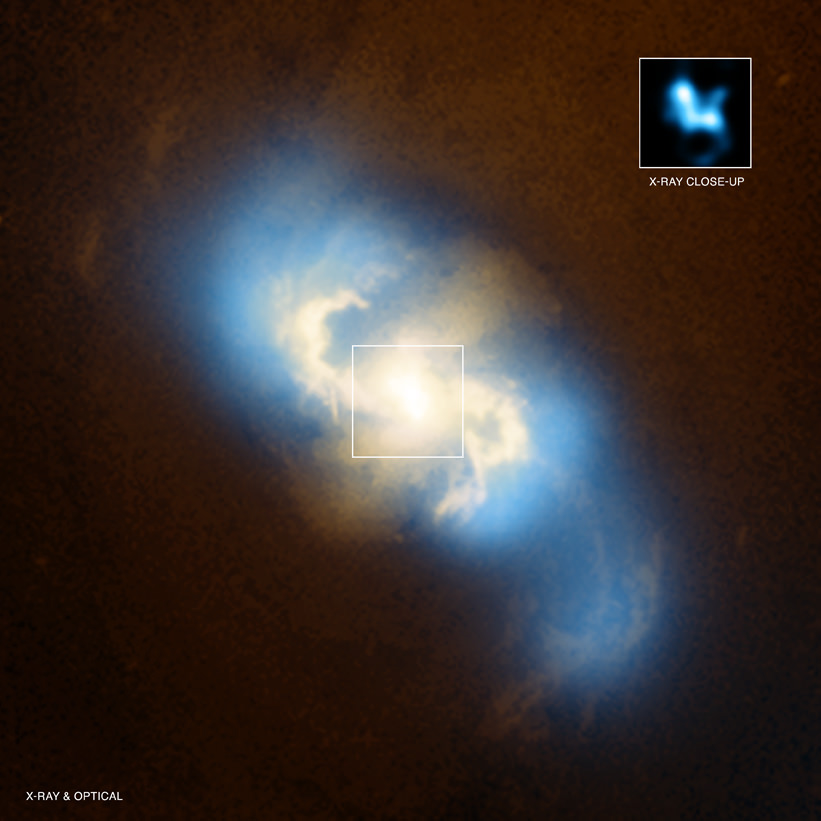

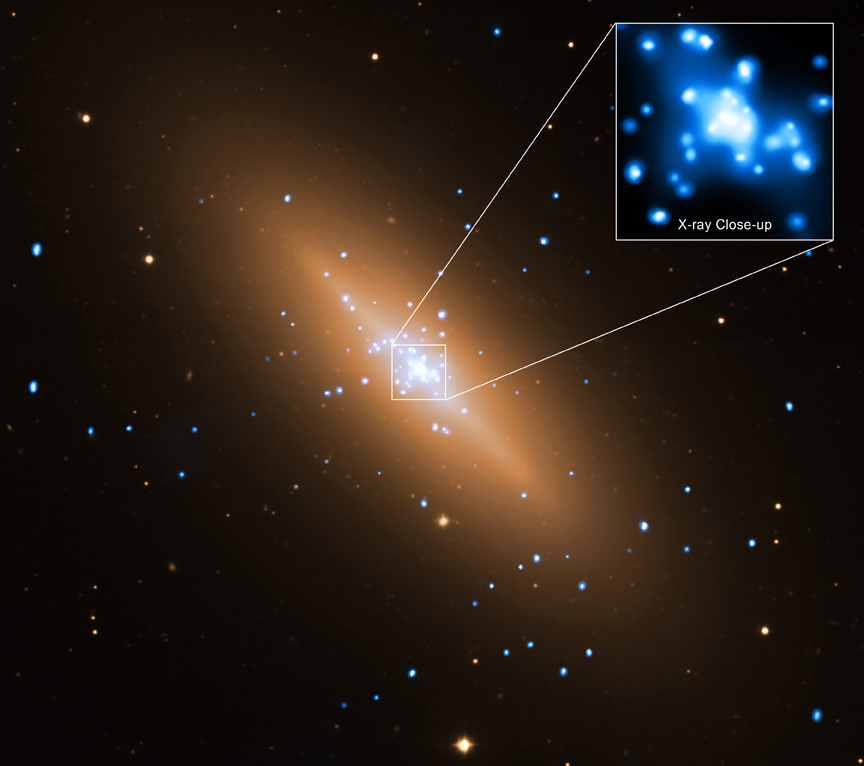

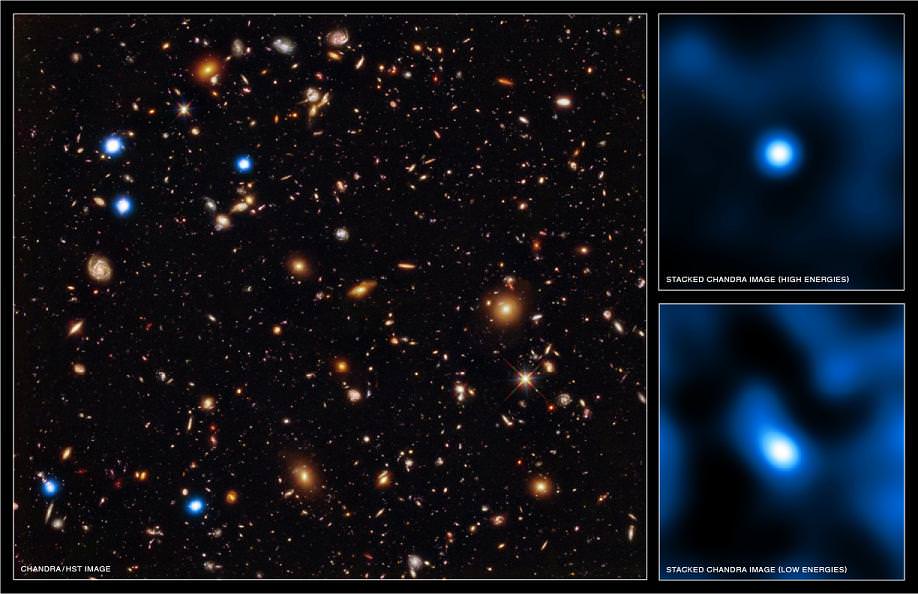

An international team of astronomers using five different telescopes set their sites on 460 million light-year distant Markarian 509 to check out the action surrounding its huge black hole. The imaging team included ESA’s XMM-Newton, Integral, NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, NASA’s Chandra and Swift satellites, and the ground-based telescopes WHT and PARITEL. For a hundred days they monitored Markarian 509. Why? Because it is known to have brightness variations which could mean turbulent inflow. In turn, the inner radiation then drives an outflow of gas – faster than a speeding bullet.

“XMM-Newton really led these observations because it has such a wide X-ray coverage, as well as an optical monitoring camera,” says Jelle Kaastra, SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research, who coordinated an international team of 26 astronomers from 21 institutes on four continents to make these observations.

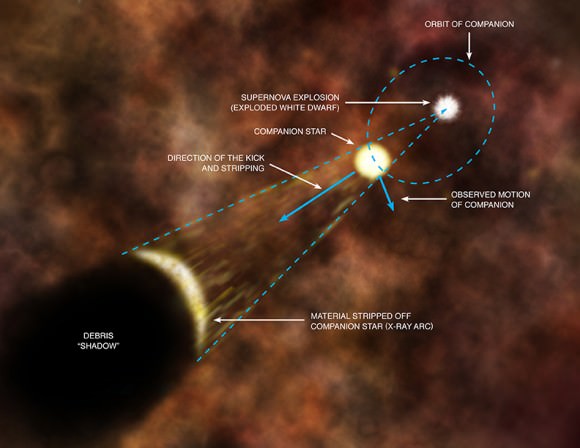

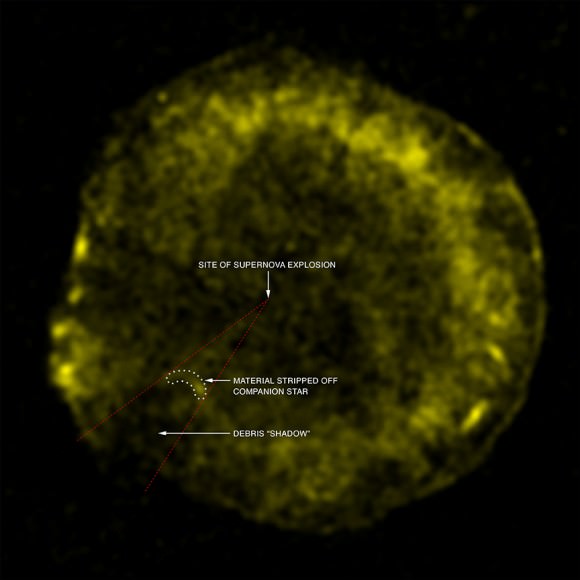

And the vampire reared its ugly head. Instead of the previously documented 25% changes, it jumped to 60%. The hot corona surrounding the black hole was spattering out cold gas “bullets” at speeds in excess of one million miles per hour. These projectiles are torn away from the dusty torus, but the real surprise is that they are coming from an area just 15 light years away from the center. This is a lot further than most astronomers speculate could happen.

“There has been a debate in astronomy for some time about the origin of the outflowing gas,” says Kaastra.

But there’s more than just bullets here. These new observations at multiple wavelengths are showing the coolest gas in the line of sight toward Markarian 509 has 14 different velocity components – all from different locations at the galaxy’s heart. What’s more, there’s indications the black hole accretion disc may have a shield of gas harboring temperatures ranging in the millions of degrees – the motivating force behind x-rays and gamma rays.

“The only way to explain this is by having gas hotter than that in the disc, a so-called ‘corona’, hovering above the disc,” Jelle Kaastra says. “This corona absorbs and reprocesses the ultraviolet light from the disc, energising it and converting it into X-ray light. It must have a temperature of a few million degrees. Using five space telescopes, which enabled us to observe the area in unprecedented detail, we actually discovered a very hot ‘corona’ of gas hovering above the disc. This discovery allows us to make sense of some of the observations of active galaxies that have been hard to explain so far.”

To make things even more entertaining, the study has also found the signature of interstellar gas which may have been the result of a one-time galaxy collision. Although the evidence may be hundreds of thousands of light years away from Mrk 509, it may have initially triggered this activity.

“The results underline how important long-term observations and monitoring campaigns are to gain a deeper understanding of variable astrophysical objects. XMM-Newton made all the necessary organisational changes to enable such observations, and now the effort is paying off,” says Norbert Schartel, ESA XMM-Newton Project Scientist.

Ah, Markarian 509… “Despite all my rage… I am still just a rat in cage.”

Original Story Source: ESA News. For Further Reading: Multiwavelength Campaign on Mrk 509 VI. HST/COS Observations of the Far-ultraviolet Spectrum.