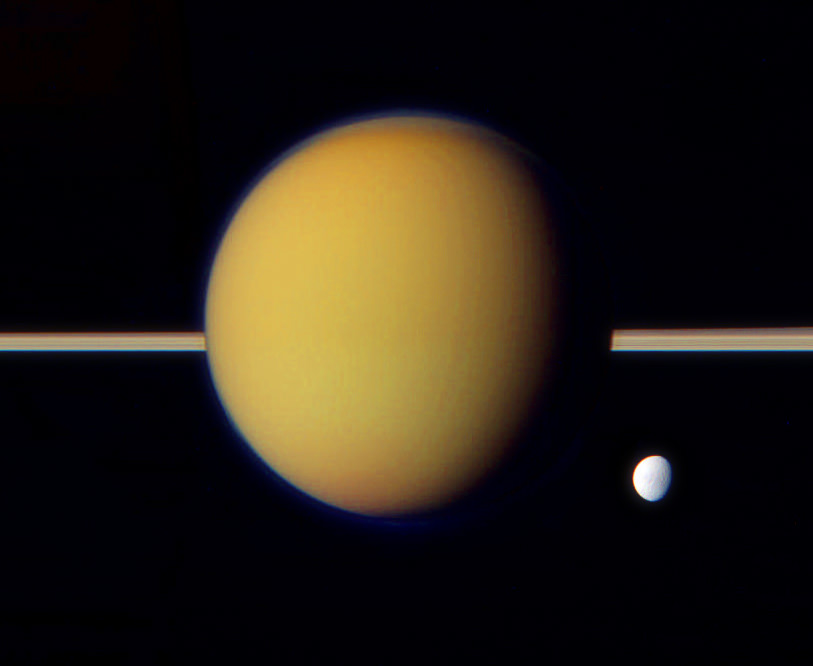

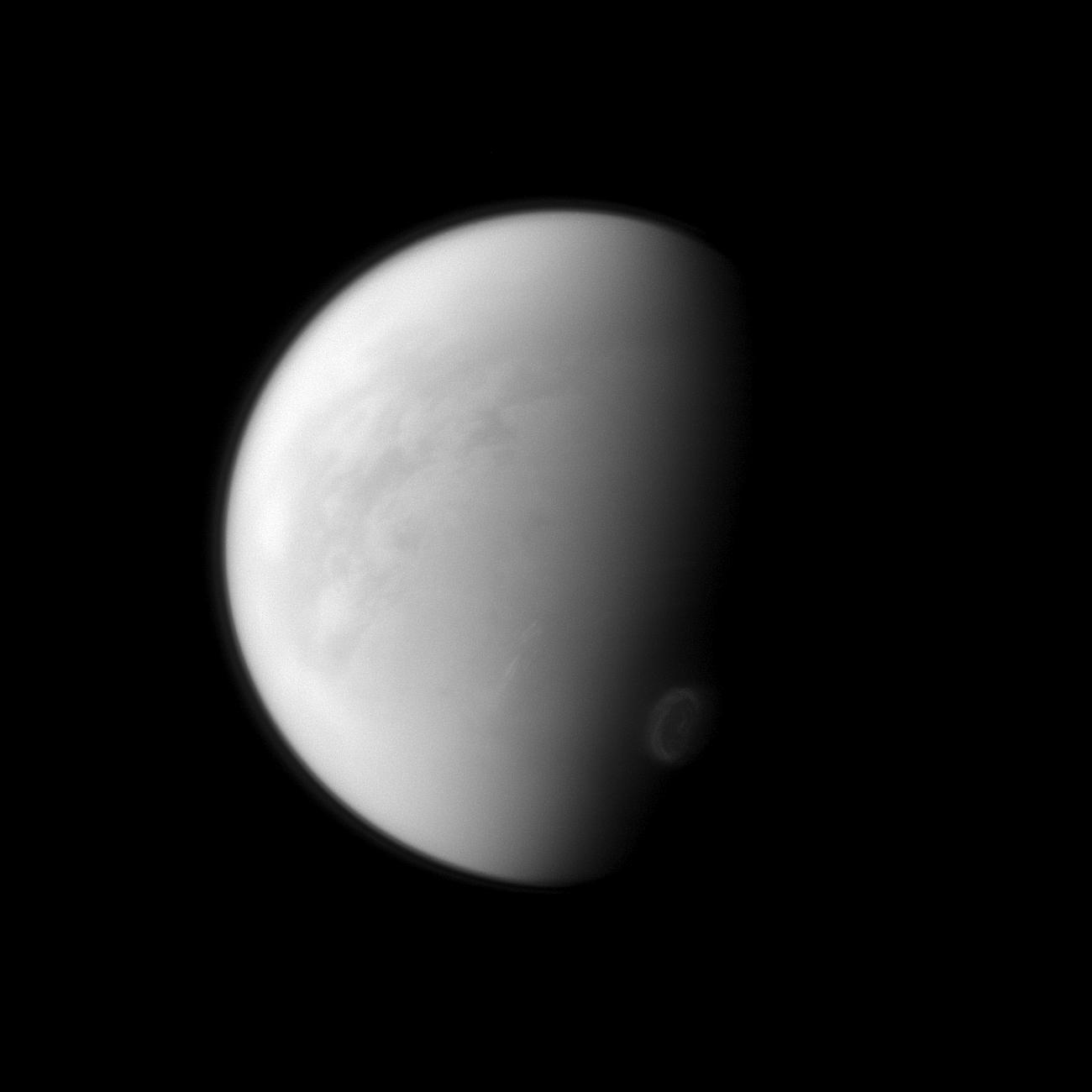

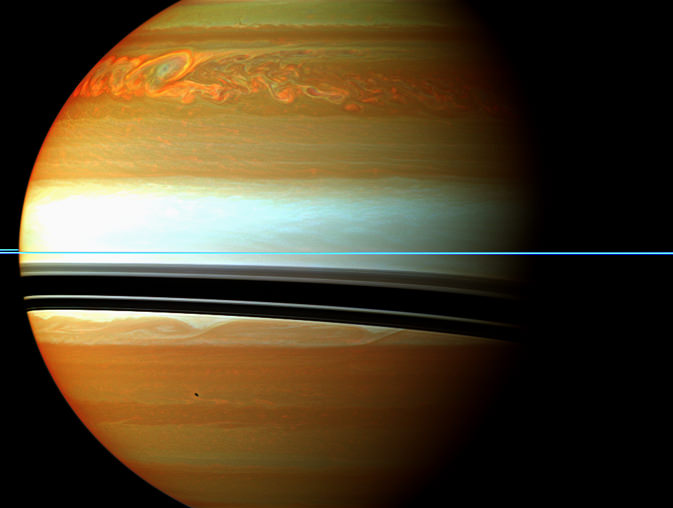

Color composite of Titan and Dione made from Cassini images acquired in May 2011. (NASA/JPL/SSI/J. Major)

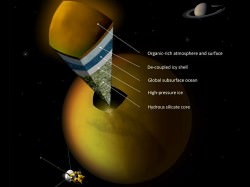

It’s long been speculated that Saturn’s moon Titan may be harboring a global subsurface ocean below an icy crust, based on measurements of its rotation and orbit by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft. Titan exhibits a density and shape that indicates a pliable liquid internal layer — an underground ocean — possibly composed of water mixed with ammonia, a combination that would help explain the consistent amount of methane found in its thick atmosphere.

Now, further analysis of Cassini gravity measurements by a Stanford University team has shown that Titan’s ice layer is thicker and less uniform than originally estimated, indicating a more complex internal structure — and a stronger external influences for its heat.

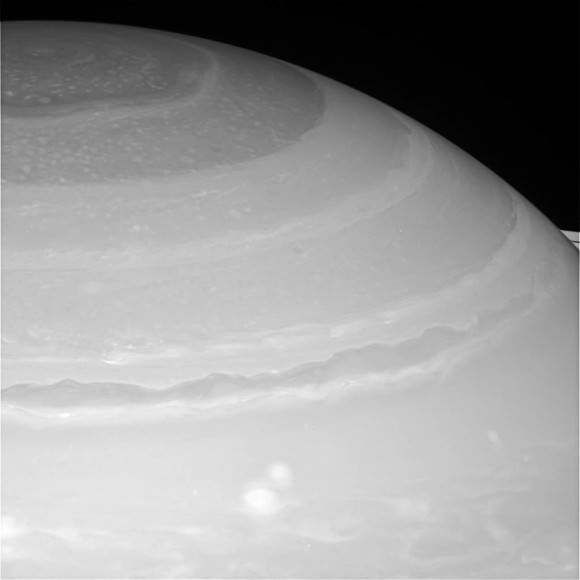

Titan’s liquid subsurface ocean was previously estimated to be in the neighborhood of 100 km (62 miles) thick, sandwiched between a rocky core below and an icy shell above. This was based on the behavior of Titan in its orbit — or, more precisely, how Titan’s shape changes along the course of its orbit, as measured by Cassini’s radar instrument.

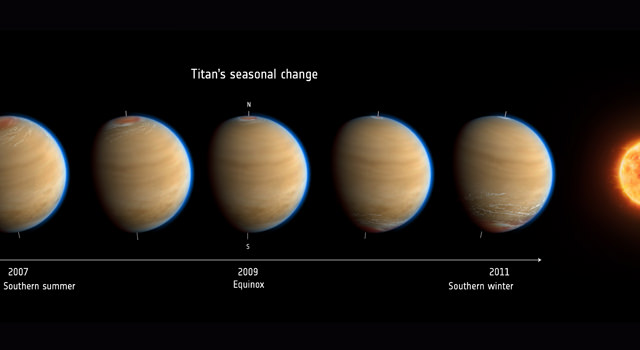

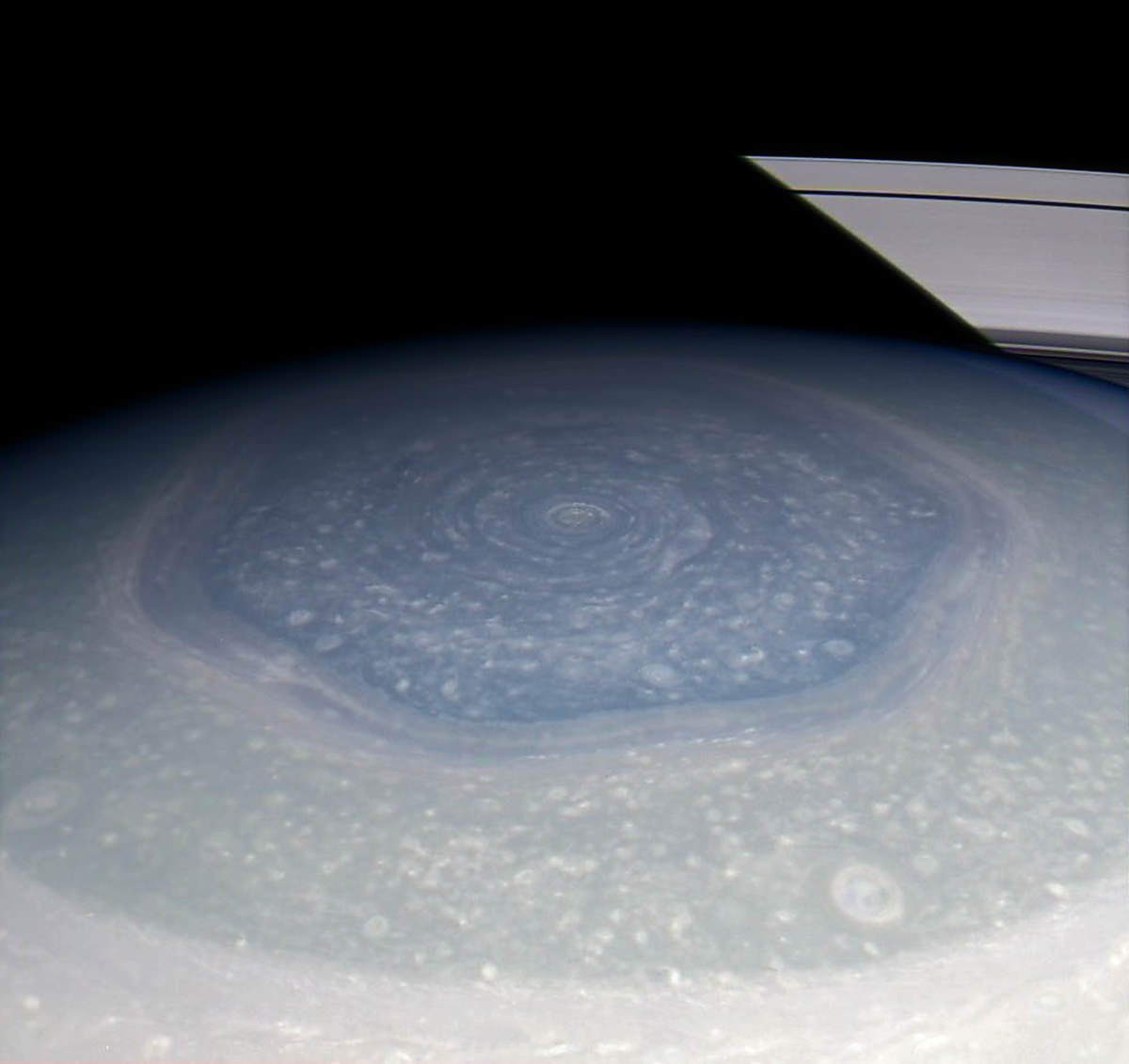

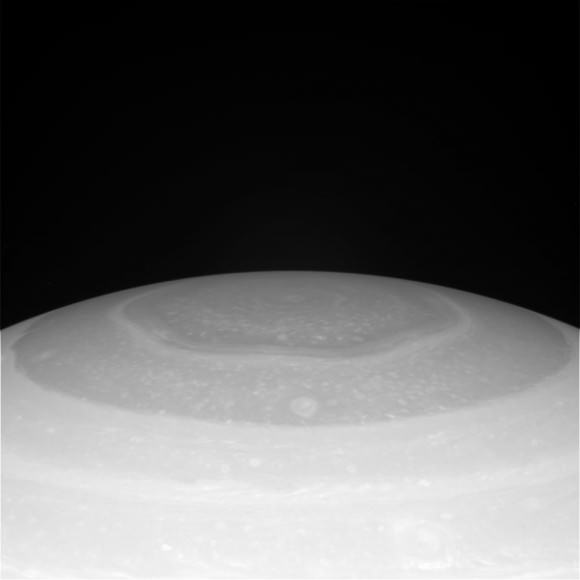

Because Titan’s 16-day orbit is not perfectly circular the moon experiences a stronger gravitational pull from Saturn at certain points than at others. As a result it’s flattened at the poles and constantly changing shape slightly — an effect called tidal flexing. Along with the decay of radioactive materials in its core, this flexing generates the internal heat that helps keep a subsurface ocean liquid.

A team of researchers from Stanford University, led by Howard Zebker, professor of geophysics and electrical engineering, used recent Cassini measurements of Titan’s topography and gravity to determine that the icy layer between the moon’s surface and ocean is up to twice as thick as previously thought — and it’s considerably thicker at the equator than at the poles.

A team of researchers from Stanford University, led by Howard Zebker, professor of geophysics and electrical engineering, used recent Cassini measurements of Titan’s topography and gravity to determine that the icy layer between the moon’s surface and ocean is up to twice as thick as previously thought — and it’s considerably thicker at the equator than at the poles.

“The picture of Titan that we get has an icy, rocky core with a radius of a little over 2,000 kilometers, an ocean somewhere in the range of 225 to 300 kilometers thick and an ice layer that is 200 kilometers thick,” said Zebker.

Different thicknesses of Titan’s ice layer would mean that there’s less heat being generated internally by the decay of radioactive materials in Titan’s core, because that type of heat would be more or less globally uniform. Instead, tidal flexing caused by the gravitational interactions with Saturn and neighboring smaller moons must play a stronger role in heating Titan’s insides.

Read more: Titan’s Tides Suggest a Subsurface Sea

With Cassini’s new measurements of Titan’s gravity, Zebker and his team calculated that the icy layer below Titan’s flattened poles is 3,000 meters (about 1.8 miles) thinner than average, while at the equator it’s 3,000 meters thicker than average. Combined with the moon’s surface features, this makes the average global thickness of the ice layer to be more like 200 km, not 100.

Heat generated by tidal flexing — which is more strongly felt at the poles — is thought to be the cause of the thinner ice there. Thinner ice would mean there’s more liquid water beneath the poles, which is denser and thus would exert a stronger gravitational pull… exactly what’s been found in Cassini’s measurements.

The findings were announced Tuesday, Dec. 4 at the AGU convention in San Francisco. Read more on the Stanford University news page.