NASA’s New Millennium Program (NMP) was conceived as a way to accelerate the use of advanced technologies into operational science missions. “It was recognized that there were significant investments being made by the United States in advanced technologies,” said Dr. Christopher Stevens, the Program Manager for NMP, “and that they had real applications to either reducing the cost or providing new capability for science missions.” However, bringing these technologies into actual science missions in space is a high risk because of the uncertainty that comes with emerging technology. NMP reduces those risks with validating new technology by flying and testing it in space. “We take technologies that are ready to go forward from the laboratory and mature them so they are ready to go to space,” said Stevens, “but the operational missions could be 10 to 20 years in the future.”

There are two types of missions or systems that NMP undertakes. One is an integrated system validation, where the whole flight system is the subject of the investigation. The second type is a subsystem validation mission, where small, stand alone experiments are carried on a space vehicle, but the vehicle is not part of the experiments.

NMP was jointly established in 1995 by NASA’s Office of Space Science and the Office of Earth Science, and in the past, missions were usually separated as being applicable to future Earth science or space science mission needs. NMP is now managed by NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, and focuses on the needs of three science areas: the Earth-Sun System, Solar System Exploration, and the Universe.

The program began with the Deep Space 1 mission in 1998, which was a space science, integrated system validation. DS1’s defining technology was solar electric, or ion, propulsion. “It was known that this technology had a capability to reduce the mass needed for propulsion over conventional chemical propulsion, but nobody wanted to take the risk of flying it untested in space,” said Stevens. DS1 successfully proved the effectiveness of ion propulsion, and now subsequent missions will use this type of propulsion, including the upcoming Dawn mission.

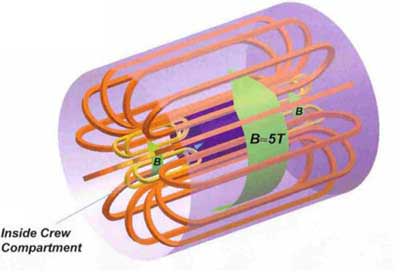

Other successful NMP validations include improvements and cost reduction of LANDSAT-type satellites and the testing of an autonomous science spacecraft which has flight planning software that can be used on rovers as well as orbiting spacecraft to re-plan a robotic mission with no human intervention. Upcoming NMP missions yet to fly include a group of small satellites called nano-sats that will make simultaneous measurements from multiple places in space of Earth’s magnetosphere, and the testing of equipment to be used on the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) mission, a joint mission between NASA and the European Space Agency. The only unsuccessful NMP mission to date was Deep Space 2, which was the Mars Microprobes that were part of the ill-fated Mars Polar Lander.

NASA recently announced the newest NMP mission, Space Technology 8, which is a subsystem validation project. It is a collection of four stand alone experiments that will travel to space on a small, low-cost, currently available spacecraft, dubbed a New Millennium carrier. The first experiment on ST8 is called Sail Mast, which is an ultra-light graphite mast. Applications for Sail Mast are spacecraft that require large membrane structures that need to be deployed, such as solar sails, telescope sunshades, large aperture optics, instrument booms, antennas or solar array assemblies. “There are a series of missions that have been identified on the NASA Roadmap for the future that could benefit from this capability,” said Stevens. “This will be a significant step forward in the mass of the structure. We are operating in a ? kg per meter mass range for a 30 or 40 meter boom that can be stowed compactly and has a reasonable stiffness.”

The second experiment is the Ultraflex Next Generation Solar Array System. This is a high power, extremely lightweight solar array. “This could be used for a mission that needs significant power in a lightweight, deployable array, such as for solar electric propulsion, or it could also be used on the surface of planetary bodies,” said Stevens. “We are looking at increasing the specific power of the array to greater than 170 watts per kilogram on an array that has at least 7 kilowatts of power.”

The third experiment is the Environmentally Adaptive Fault Tolerant Computing System. “Here the objective is to use commercial off the shelf processors configured in an architecture that is fault-tolerant to single event upsets caused by radiation,” said Stevens. “We want to show that this is a robust design that can be used in space without having to use radiation-hard parts, because you get a significant increase in processing speed and capability over currently available radiation-hard processors. We want to reduce the costs with high reliability.” This can be used for processing science data on board a spacecraft, and for autonomous control functions.

The final experiment on ST8 is the Miniature Loop Heat Pipe Small Thermal Management System. “What we want to do here is to reduce the thermal constraints on small spacecraft design and manage heat and the need for cooling without expending significant amounts of power,” said Stevens. This system proposes to efficiently manage thermal balance within the spacecraft by taking heat where it is being produced by, for example, electronics, and provide it to other places in the spacecraft that need heat. It has no moving parts and doesn’t require power.

The ST8 mission should be ready for launch in 2008.

In July of 2005 NASA plans to announce the technology providers for the next NMP mission. ST9 will be an integrated system validation mission. There are five different concepts that we are being considered, and all five are regarded as areas of high priority for NASA. They are:

– Solar Sail Flight System Technology

– Aerocapture System Technology for Planetary Missions

– Precision Formation Flying System Technology

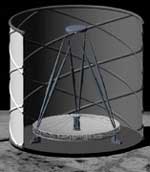

– System Technology for Large Space Telescopes

– Terrain-Guided Automatic Landing System for Spacecraft

All five concepts will be studied over the next year. Following the completion of these studies, one of the five concepts will be selected for ST9. Launch time will depend on which concept is selected, but is tentatively in the 2008-2009 time frame.

Stevens has been with NMP since it was formed, and has been program manager for 3 years. He enjoys being able to demonstrate advanced technologies so that they can be incorporated into future missions. “It’s an exciting business, a very high risk business,” he said, “because advanced technology is so uncertain in regards to how long it will take and how much it will cost.” He said that the validation of the autonomous science spacecraft experiment has been especially rewarding. “The current Mars rovers are extremely labor-intensive, but NASA has not been willing to turn over the operation of a spacecraft to a software package, so I think this validation has been a major step.” Stevens said that his office has a technology infusion activity currently going on with the Mars program, looking at using this capability for future missions, like the Mars Science Laboratory rover, scheduled for launch in 2009.

Written by Nancy Atkinson