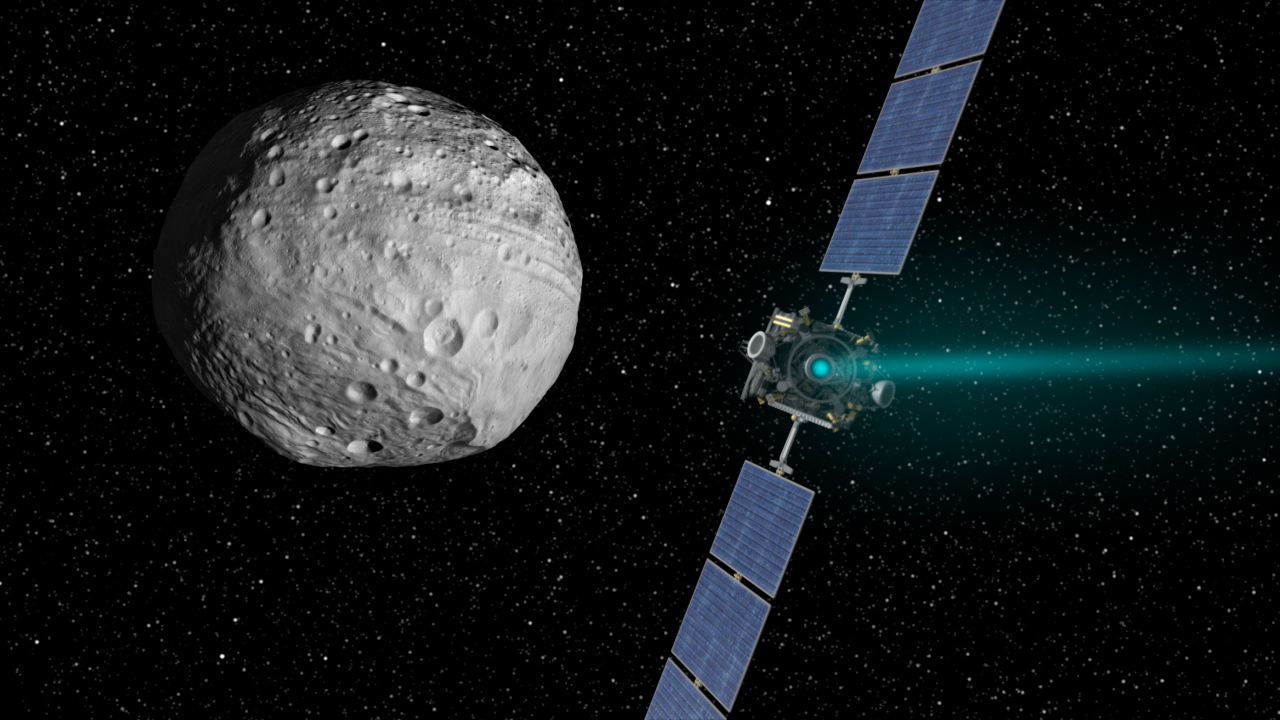

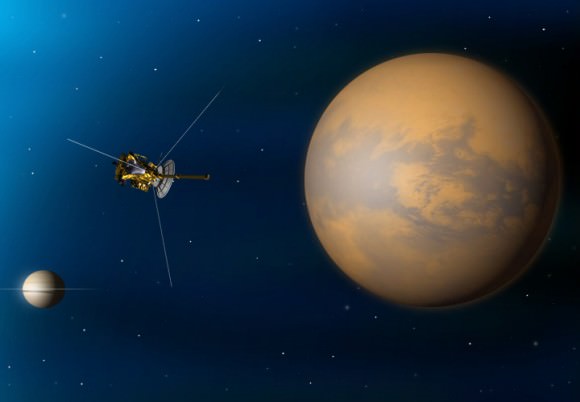

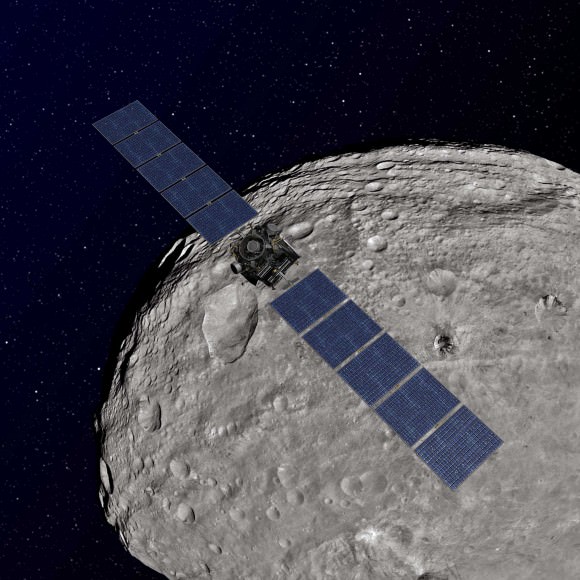

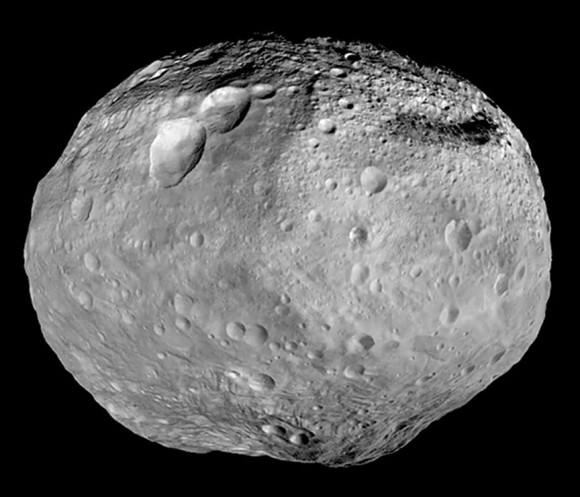

In 2011, NASA’s Dawn spacecraft established orbit around the large asteroid (aka. planetoid) known as Vesta. Over the course of the next 14 months, the probe conducted detailed studies of Vesta’s surface with its suite of scientific instruments. These findings revealed much about the planetoid’s history, its surface features, and its structure – which is believed to be differentiated, like the rocky planets.

In addition, the probe collected vital information on Vesta’s ice content. After spending the past three years sifting through the probe’s data, a team of scientists has produced a new study that indicates the possibility of subsurface ice. These findings could have implications when it comes to our understanding of how Solar bodies formed and how water was historically transported throughout the Solar System.

Their study, titled “Orbital Bistatic Radar Observations of Asteroid Vesta by the Dawn Mission“, was recently published in the scientific journal Nature Communications. Led by Elizabeth Palmer, a graduate student from Western Michigan University, the team relied on data obtained by the communications antenna aboard the Dawn spacecraft to conduct the first orbital bistatic radar (BSR) observation of Vesta.

This antenna – the High-Gain telecommunications Antenna (HGA) – transmitted X-band radio waves during its orbit of Vesta to the Deep Space Network (DSN) antenna on Earth. During the majority of the mission, Dawn’s orbit was designed to ensure that the HGA was in the line of sight with ground stations on Earth. However, during occultations – when the probe passed behind Vesta for 5 to 33 minutes at a time – the probe was out of this line of sight.

Nevertheless, the antenna was continuously transmitting telemetry data, which caused the HGA-transmitted radar waves to be reflected off of Vesta’s surface. This technique, known as bistatic radar (BSR) observations has been used in the past to study the surfaces of terrestrial bodies like Mercury, Venus, the Moon, Mars, Saturn’s moon Titan, and the comet 67P/CG.

But as Palmer explained, using this technique to study a body like Vesta was a first for astronomers:

“This is the first time that a bistatic radar experiment was conducted in orbit around a small body, so this brought several unique challenges compared to the same experiment being done at large bodies like the Moon or Mars. For example, because the gravity field around Vesta is much weaker than Mars, the Dawn spacecraft does not have to orbit at a very high speed to maintain its distance from the surface. The orbital speed of the spacecraft becomes important, though, because the faster the orbit, the more the frequency of the ‘surface echo’ gets changed (Doppler shifted) compared to the frequency of the ‘direct signal’ (which is the unimpeded radio signal that travels directly from Dawn’s HGA to Earth’s Deep Space Network antennas without grazing Vesta’s surface). Researchers can tell the difference between a ‘surface echo’ and the ‘direct signal’ by their difference in frequency—so with Dawn’s slower orbital speed around Vesta, this frequency difference was very small, and required more time for us to process the BSR data and isolate the ‘surface echoes’ to measure their strength.”

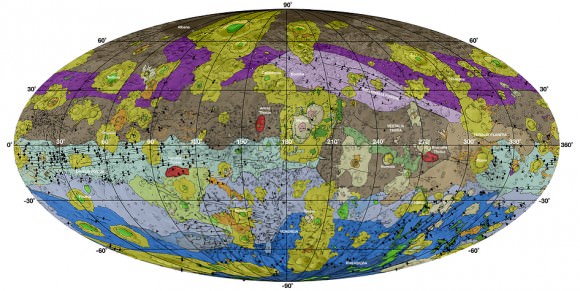

By studying the reflected BSR waves, Palmer and her team were able to gain valuable information from Vesta’s surface. From this, they observed significant differences in surface radar reflectivity. But unlike the Moon, these variations in surface roughness could not be explained by cratering alone and was likely due to the existence of ground-ice. As Palmer explained:

“We found that this was the result of differences in the roughness of the surface at the scale of a few inches. Stronger surface echoes indicate smoother surfaces, while weaker surface echoes have bounced off of rougher surfaces. When we compared our surface roughness map of Vesta with a map of subsurface hydrogen concentrations—which was measured by Dawn scientists using the Gamma Ray and Neutron Detector (GRaND) on the spacecraft—we found that extensive smoother areas overlapped areas that also had heightened hydrogen concentrations!”

In the end, Palmer and her colleagues concluded that the presence of buried ice (past and/or present) on Vesta was responsible for parts of the surface being smoother than others. Basically, whenever an impact happened on the surface, it transferred a great deal of energy to the subsurface. If buried ice was present there, it would be melted by the impact event, flow to the surface along impact-generated fractures, and then freeze in place.

Much in the same way that moon’s like Europa, Ganymede and Titania experience surface renewal because of the way cryovolcanism causes liquid water to reach the surface (where it refreezes), the presence of subsurface ice would cause parts of Vesta’ surface to be smoothed out over time. This would ultimately lead to the kinds of uneven terrain that Palmer and her colleagues witnessed.

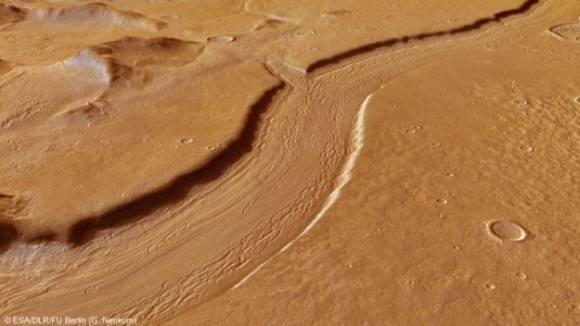

This theory is supported by the large concentrations of hydrogen that were detected over smoother terrains that measure hundreds of square kilometers. It is also consistent with geomorphological evidence obtained from the Dawn Framing Camera images, which showed signs of of transient water flow over Vesta’s surface. This study also contradicted some previously-held assumptions about Vesta.

As Palmer noted, this could also have implications as far as our understanding of the history and evolution of the Solar System is concerned:

“Asteroid Vesta was expected to have depleted any water content long ago through global melting, differentiation, and extensive regolith gardening by impacts from smaller bodies. However, our findings support the idea that buried ice may have existed on Vesta, which is an exciting prospect since Vesta is a protoplanet that represents an early stage in the formation of a planet. The more we learn about where water-ice exists throughout the Solar System, the better we will understand how water was delivered to Earth, and how much was intrinsic to Earth’s interior during the early stages of its formation.”

This work was sponsored by NASA’s Planetary Geology and Geophysics program, a JPL-based effort that focuses on fostering the research of terrestrial-like planets and major satellites in the Solar System. The work was also conducted with the assistance of the USC’s Viterbi School of Engineering as part of an ongoing effort to improve radar and microwave imaging to locate subsurface sources of water on planets and other bodies.

Further Reading: USC, Nature Communications