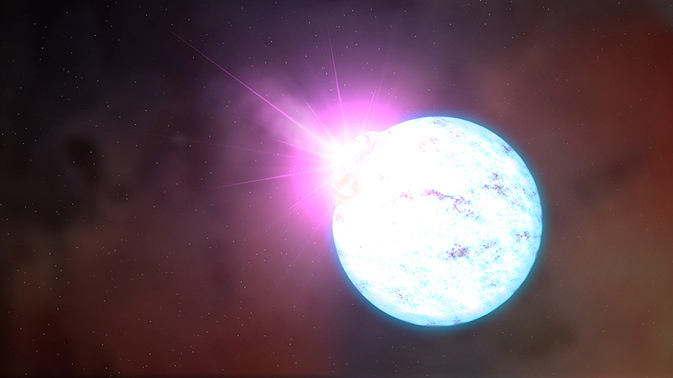

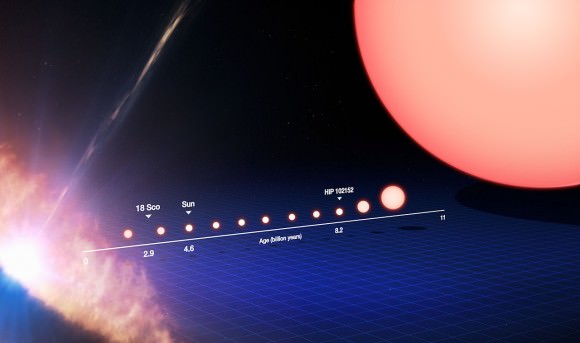

When low- to middleweight stars like our Sun approach the end of their life cycles they eventually cast off their outer layers, leaving behind a dense, white dwarf star. These outer layers became a massive cloud of dust and gas, which is characterized by bright colors and intricate patterns, known as a planetary nebula. Someday, our Sun will turn into such a nebula, one which could be viewed from light-years away.

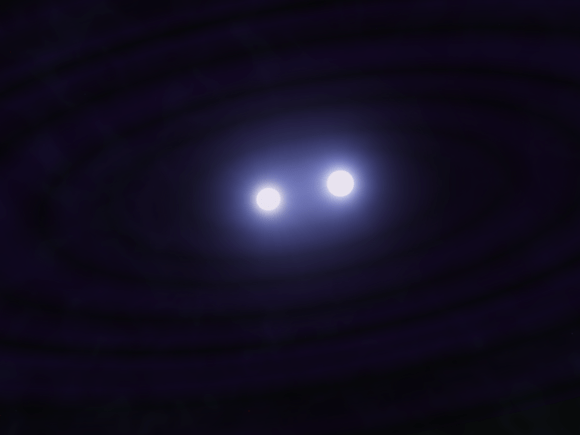

This process, where a dying star gives rise to a massive cloud of dust, was already known to be incredibly beautiful and inspiring thanks to many images taken by Hubble. However, after viewing the famous Ant Nebula with the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Herschel Space Observatory, a team of astronomers discovered an unusual laser emission that suggests that there is a double star system at the center of the nebula.

The study, titled “Herschel Planetary Nebula Survey (HerPlaNS): hydrogen recombination laser lines in Mz 3“, recently appeared in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. The study was led by Isabel Aleman of the the Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics, the and multiple universities.

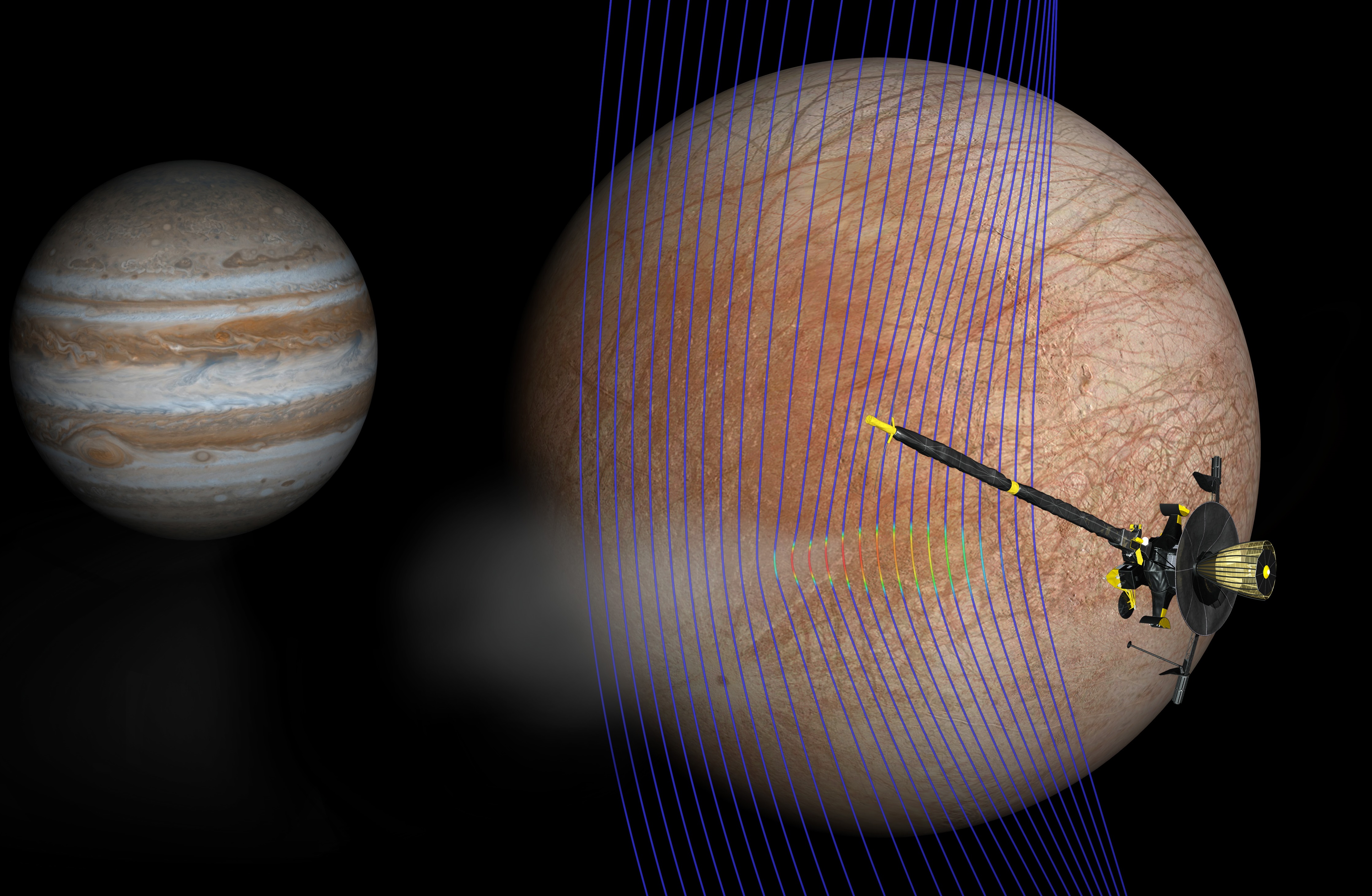

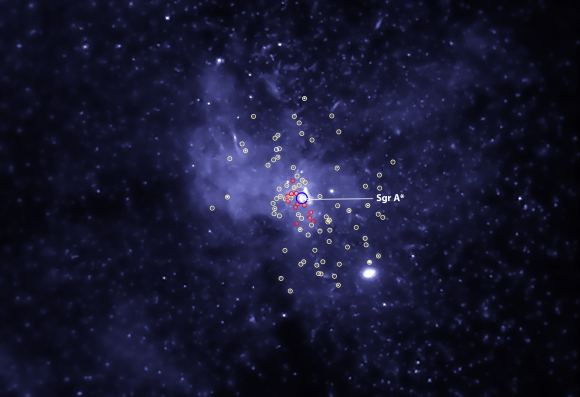

The Ant Nebula (aka. Mz 3) is a young bipolar planetary nebula located in the constellation Norma, and takes its name from the twin lobes of gas and dust that resemble the head and body of an ant. In the past, this nebula’s beautiful and intricate nature was imaged by the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. The new data obtained by Herschel also indicates that the Ant Nebula beams intense laser emissions from its core.

In space, infrared laser emissions are detected at very different wavelengths and only under certain conditions, and only a few of these space lasers are known. Interestingly enough, it was astronomer Donald Menzel – who first observed and classified the Ant Nebula in 1920 (hence why it is officially known as Menzel 3 after him) – who was one of the first to suggest that lasers could occur in nebula.

According to Menzel, under certain conditions natural “light amplification by the stimulated emissions of radiation” (aka. where we get the term laser from) would occur in space. This was long before the discovery of lasers in laboratories, an occasion that is celebrated annually on May 16th, known as UNESCO’s International Day of Light. As such, it was highly appropriate that this paper was also published on May 16th, celebrating the development of the laser and its discoverer, Theodore Maiman.

As Isabel Aleman, the lead author of a paper, described the results:

“When we observe Menzel 3, we see an amazingly intricate structure made up of ionized gas, but we cannot see the object in its center producing this pattern. Thanks to the sensitivity and wide wavelength range of the Herschel observatory, we detected a very rare type of emission called hydrogen recombination line laser emission, which provided a way to reveal the nebula’s structure and physical conditions.”

“Such emission has only been identified in a handful of objects before and it is a happy coincidence that we detected the kind of emission that Menzel suggested, in one of the planetary nebulae that he discovered,” she added.

The kind of laser emission they observed needs very dense gas close to the star. By comparing observations from the Herschel observatory to models of planetary nebula, the team found that the density of the gas emitting the lasers was about ten thousand times denser than the gas seen in typical planetary nebulae, and in the lobes of the Ant Nebula itself.

Normally, the region close to the dead star – in this case, roughly the distance between Saturn and the Sun – is quite empty because its material was ejected outwards after the star went supernova. Any lingering gas would soon fall back onto it. But as Professor Albert Zijlstra, from the Jodrell Bank Center for Astrophysics and a co-author on the study, put it:

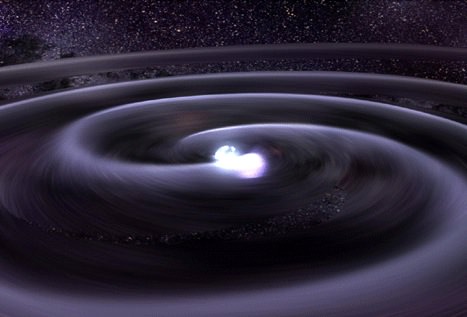

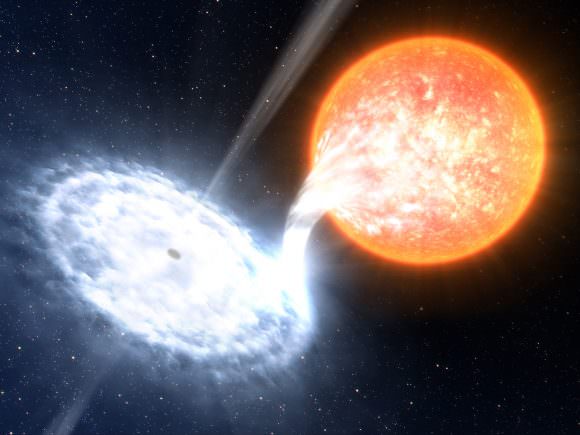

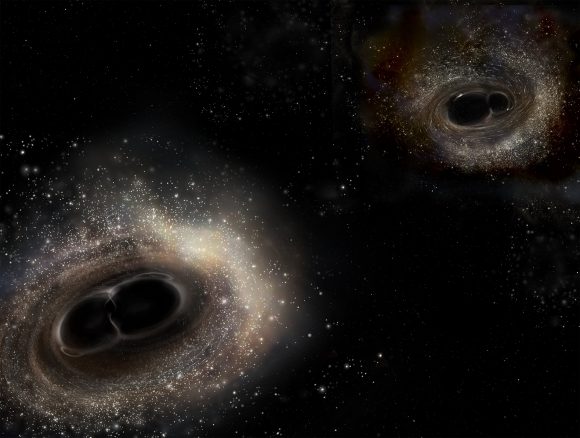

“The only way to keep such dense gas close to the star is if it is orbiting around it in a disc. In this nebula, we have actually observed a dense disc in the very center that is seen approximately edge-on. This orientation helps to amplify the laser signal. The disc suggests there is a binary companion, because it is hard to get the ejected gas to go into orbit unless a companion star deflects it in the right direction. The laser gives us a unique way to probe the disc around the dying star, deep inside the planetary nebula.”

While astronomers have not yet seen the expected second star, they are hopeful that future surveys will be able to locate it, thus revealing the origin of the Ant Nebula’s mysterious lasers. In so doing, they will be able to connect two discoveries (i.e. planetary nebula and laser) made by the same astronomer over a century ago. As Göran Pilbratt, ESA’s Herschel project scientist, added:

“This study suggests that the distinctive Ant Nebula as we see it today was created by the complex nature of a binary star system, which influences the shape, chemical properties, and evolution in these final stages of a star’s life. Herschel offered the perfect observing capabilities to detect this extraordinary laser in the Ant Nebula. The findings will help constrain the conditions under which this phenomenon occurs, and help us to refine our models of stellar evolution. It is also a happy conclusion that the Herschel mission was able to connect together Menzel’s two discoveries from almost a century ago.”

Next-generation space telescopes that could tell us more about planetary nebula and the life-cycles of stars include the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). Once this telescope takes to space in 2020, it will use its advanced infrared capabilities to see objects that are otherwise obscured by gas and dust. These studies could reveal much about the interior structures of nebulae, and perhaps shed light on why they periodically shoot out “space lasers”.

Further Reading: University of Manchester, ESA, MNRAS