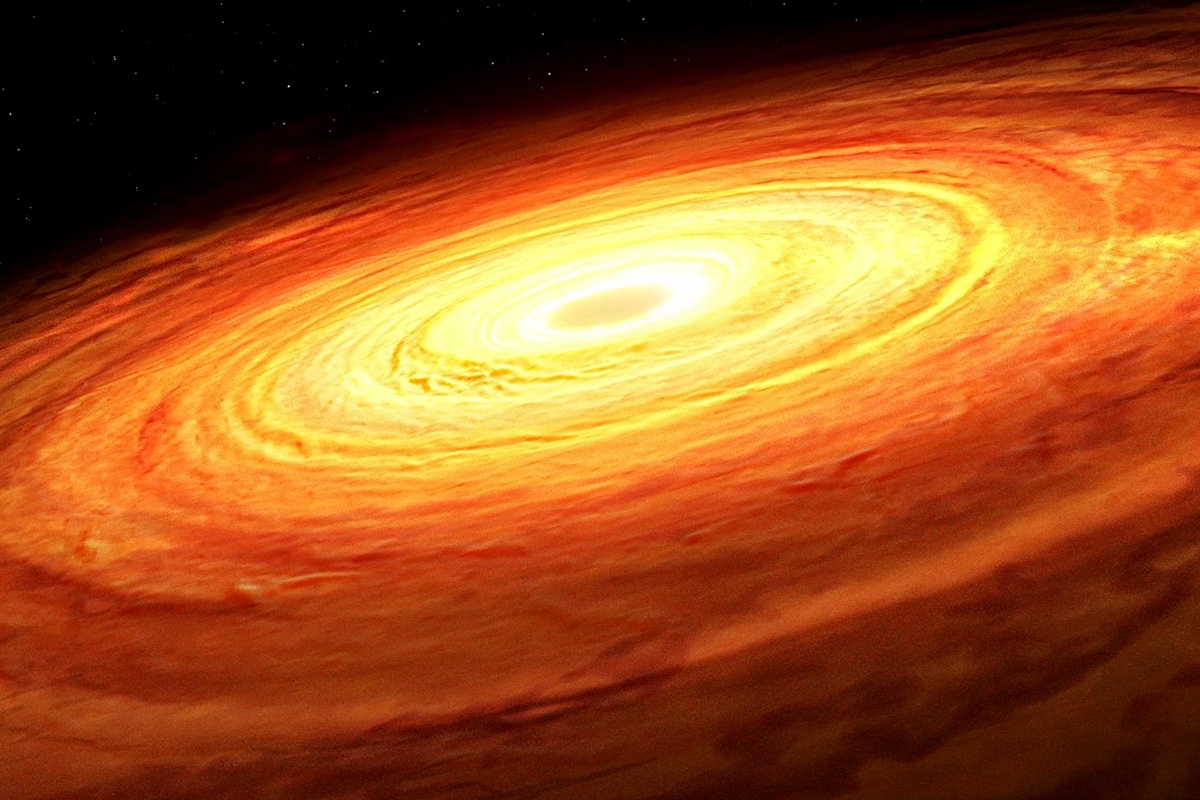

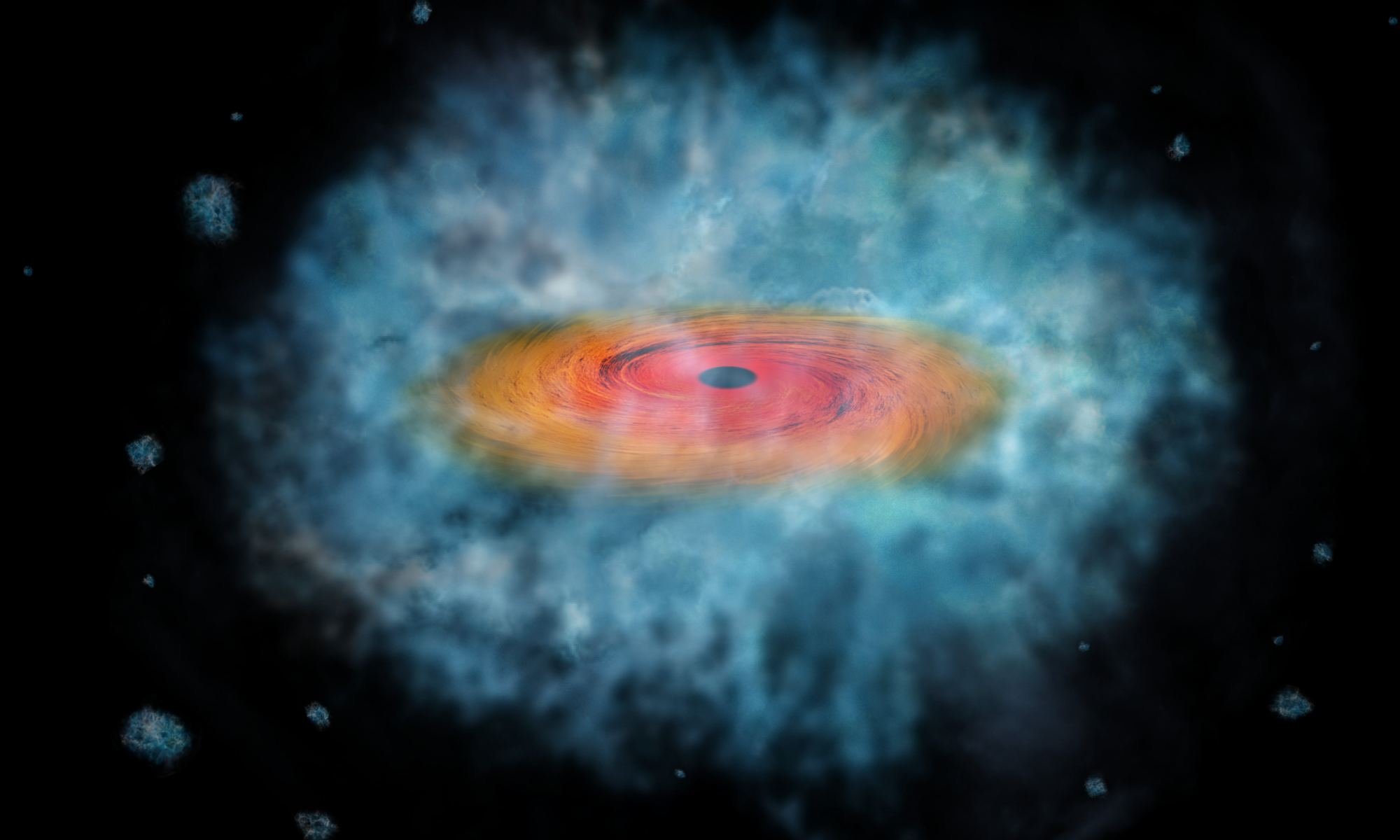

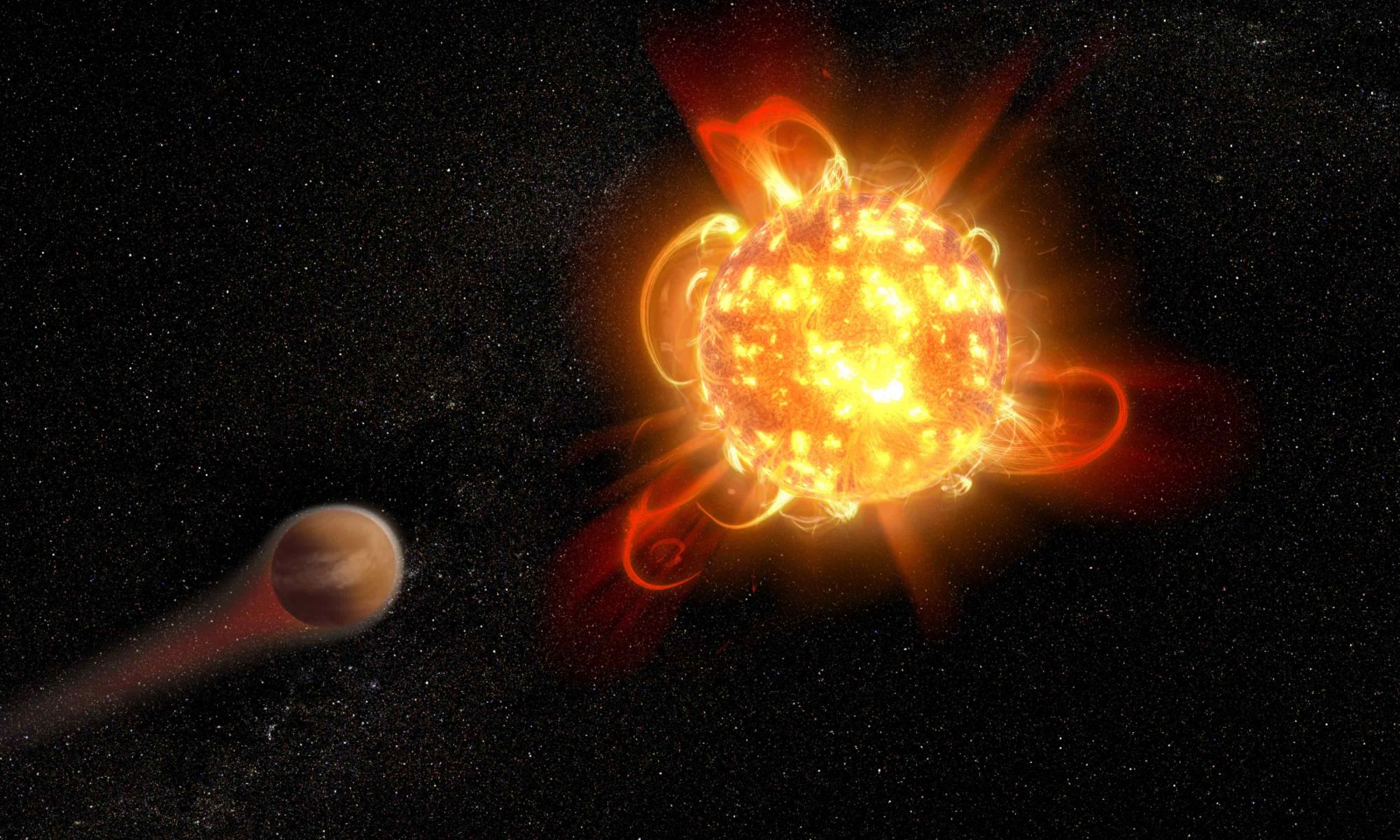

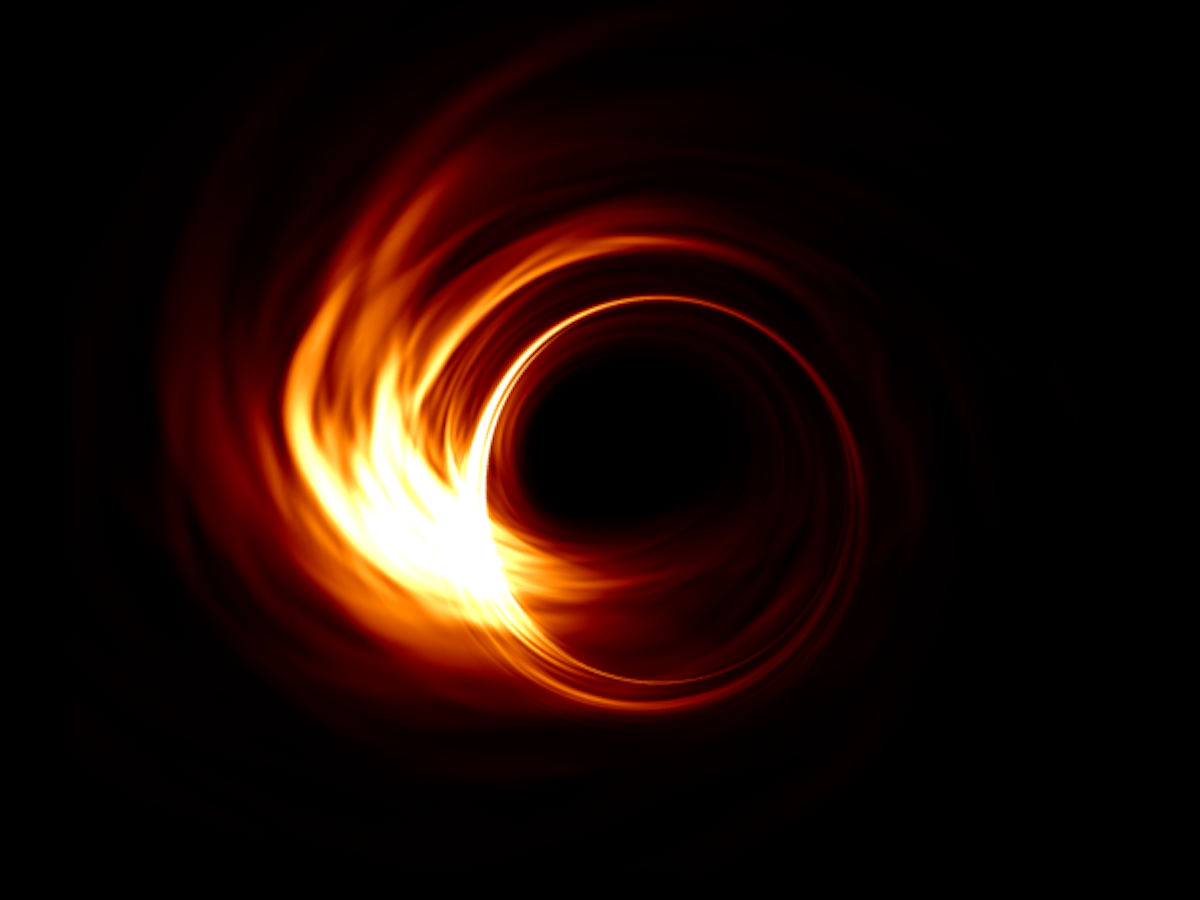

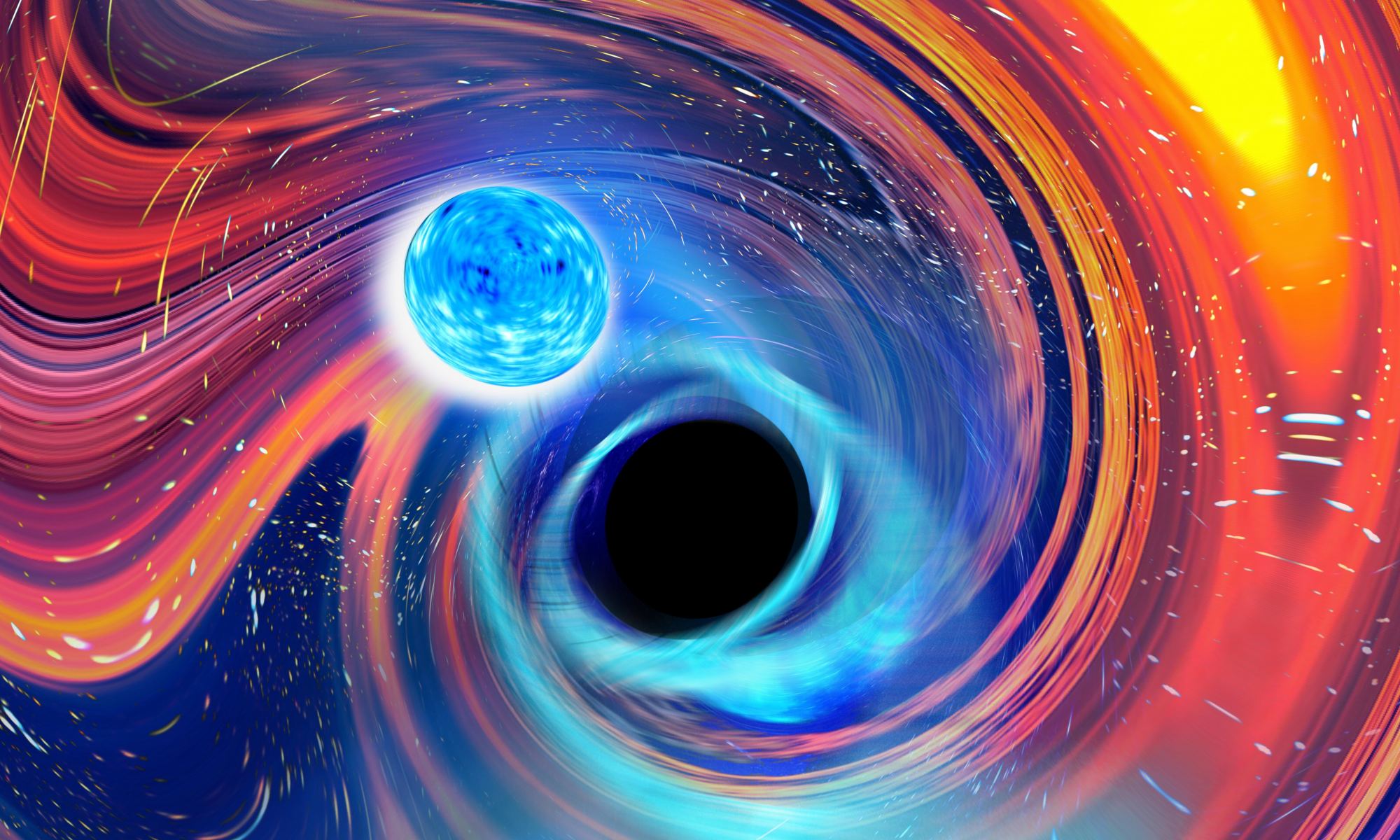

Black holes don’t emit light, which makes them difficult to study. Fortunately, many black holes are loud eaters. As they consume nearby matter, surrounding material is superheated. As a result, the material can glow intensely, or be thrown away from the black hole as relativistic jets. By studying the light from this material we can study black holes. And as a recent study shows, we can even determine their size.

Continue reading “You can Tell how big a Black Hole is by how it Eats”You can Tell how big a Black Hole is by how it Eats