Call it a porcine occultation. It took nearly a year but I finally got help from the ornamental pig in my wife’s flower garden. This weekend it became the preferred method for blocking the sun to better see and photograph a beautiful pair of solar halos. We often associate solar and lunar halos with winter because they require ice crystals for their formation, but they happen during all seasons.

Lower clouds, like the puffy cumulus dotting the sky on a summer day, are composed of water droplets. A typical cumulus spans about a kilometer and contains 1.1 million pounds of water. Cirrostratus clouds are much higher (18,000 feet and up) and colder and formed instead of ice crystals. They’re often the first clouds to betray an incoming frontal system.

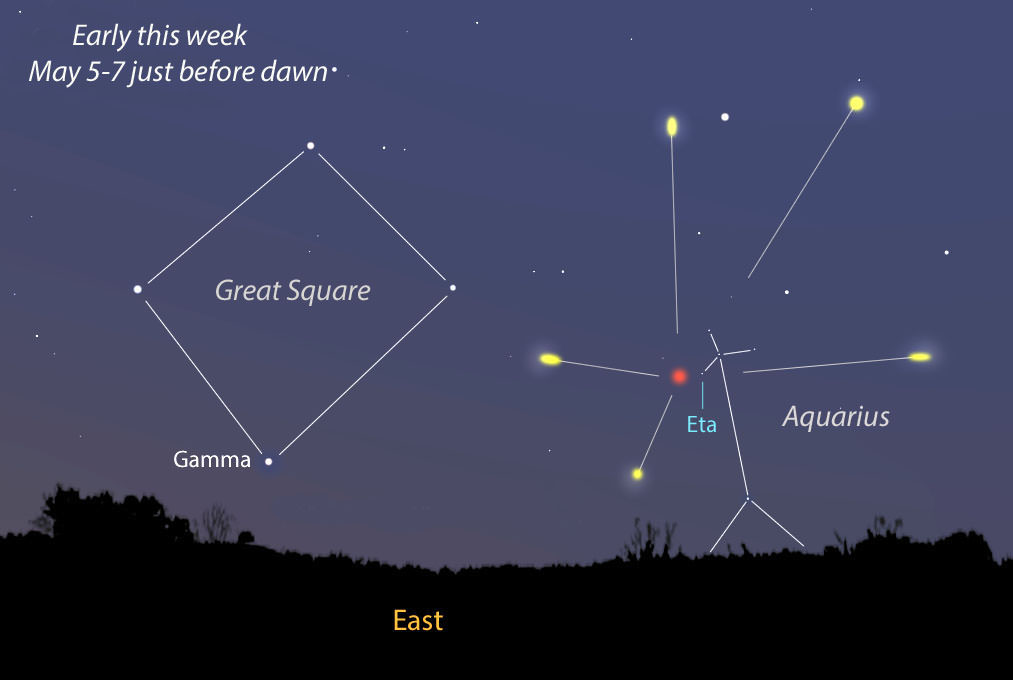

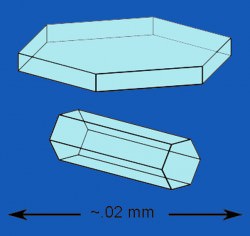

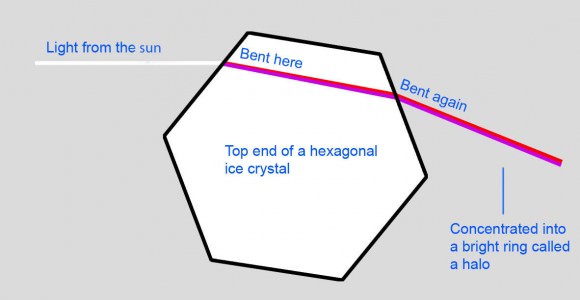

Cirrostratus are thin and fibrous and give the blue sky a milky look. Most halos and related phenomena originate in countless millions of hexagonal plate and pencil-shaped ice crystals wafting about like diamond dust in these often featureless clouds.

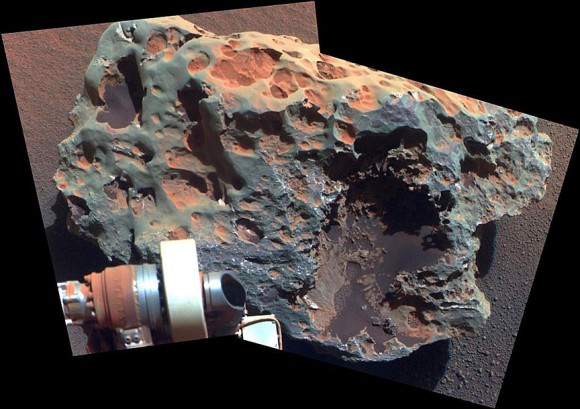

In winter, the sun is generally low in the sky, making it hard to miss a halo. Come summer, when the sun is much higher up, halo spotters have to be more deliberate and make a point to look up more often. The 22-degree halo is the most common; it’s the inner of the two halos in the photo above. With a radius of 22 degrees, an outstretched hand at arm’s length will comfortably fit between sun and circle.

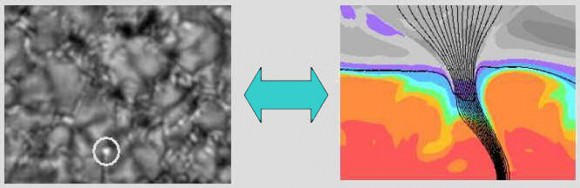

Light refracted or bent through millions of randomly oriented pencil-shaped crystals exits at angles from 22 degrees up to 50 degrees, however most of the light is concentrated around 22 degrees, resulting in the familiar 22-degree radius halo. No light gets bent and concentrated at angles fewer than 22 degrees, which is why the sky looks darker inside the halo than outside. Finally, a small fraction of the light exits the crystals between 22 and 50 degrees creating a soft outer edge to the circle as well as a large, more diffuse disk of light as far as 50 degrees from the sun.

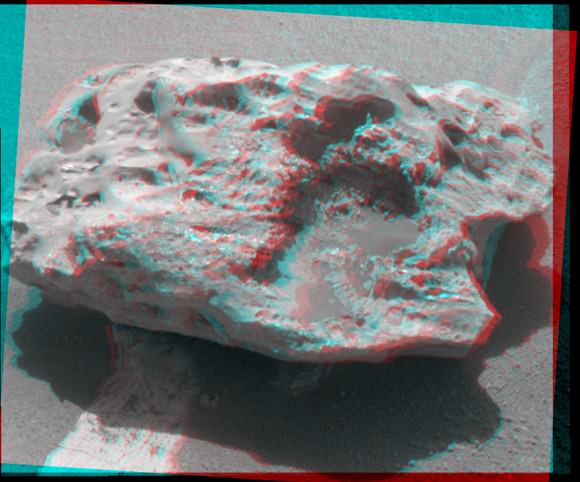

Sundogs, also called mock suns or parhelia, are brilliant and often colorful patches of light that accompany the sun on either side of a halo. Not as frequent as halos, they’re still common enough to spot half a dozen times or more a year. Depending on how extensive the cloud cover is, you might see only one sundog instead of the more typical pair. Sundogs form when light refracts through hexagonal plate-shaped ice crystals with their flat sides parallel to the ground. They appear when the sun is near the horizon and on the same horizontal plane as the ice crystals. As in halos, red light is refracted less than blue, coloring the dog’s ‘head’ red and its hind quarters blue. Mock sun is an apt term as occasionally a sundog will shine with the intensity of a second sun. They’re responsible for some of the daytime ‘UFO’ sightings. Check this one one out on YouTube.

Wobbly crystals make for taller sundogs. Like real dogs, ice crystal sundogs can grow tails. These are part of the much larger parhelic circle, a rarely-seen narrow band of light encircling the entire sky at the sun’s altitude formed when millions of both plate and column crystals reflect light from their vertical faces. Short tails extend from each mock sun in the photo above.

There’s almost no end to atmospheric ice antics. Many are rare like the giant 46-degree halo or the 9 and 18-degree halos formed from pyramidal ice crystals. Oftentimes halos are accompanied by arcs or modified arcs as in the flying pig image. When the sun is low, you’ll occasionally see an arc shaped like a bird in flight tangent to the top of the halo and rarely, to its bottom. When the sun reaches an altitude of 29 degrees, these tangent arcs – both upper and lower – change shape and merge into a circumscribed halo wrapped around and overlapping the top and bottom of the main halo. At 50 degrees altitude and beyond, the circumscribed halo disappears … for a time. If the clouds persist, you can watch it return when the sun dips below 29 degrees and the two arcs separate again.

Maybe you’re not a halo watcher, but anyone who keeps an eye on the weather and studies the daytime sky in preparation for a night of skywatching can enjoy these icy appetizers.