Have an 8-inch or larger telescope? Don’t mind staying up late? Excellent. Here’s a chance to stare deeper into the known fabric of the universe than perhaps you’ve ever done before. The violent blazer 3C 454.3 is throwing a fit again, undergoing its most intense outburst seen since 2010. Normally it sleeps away the months around 17th magnitude but every few years, it can brighten up to 5 magnitudes and show in amateur telescopes. While magnitude +13 doesn’t sound impressive at first blush, consider that 3C 454.3 lies 7 billion light years from Earth. When light left the quasar, the sun and planets wouldn’t have skin in the game for another two billion years.

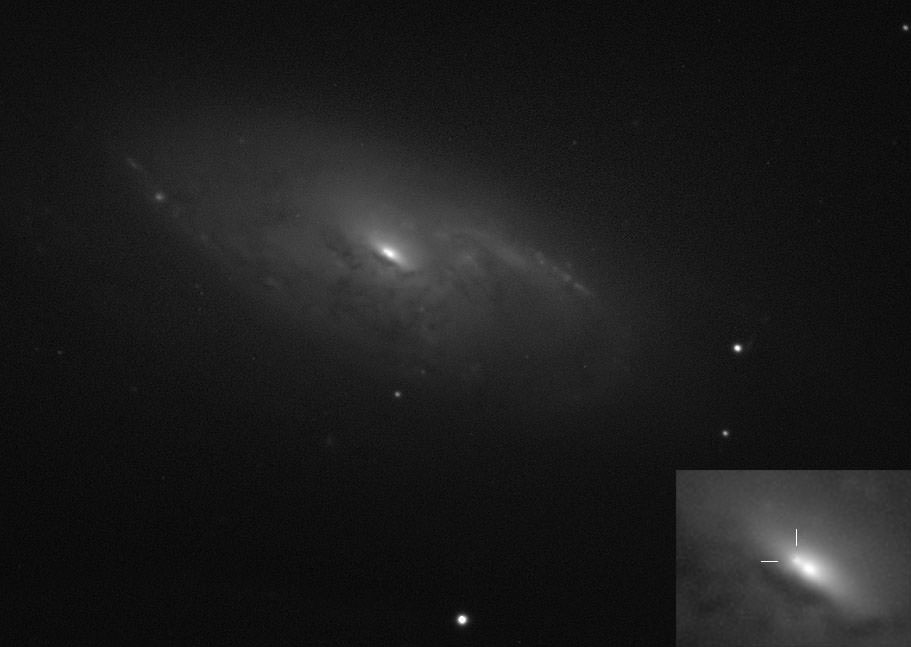

Blazars form in the the cores of active galaxies where supermassive black holes reside. Matter falling into the black hole spreads into a spinning accretion disk before spiraling down the hole like water down a bathtub drain.

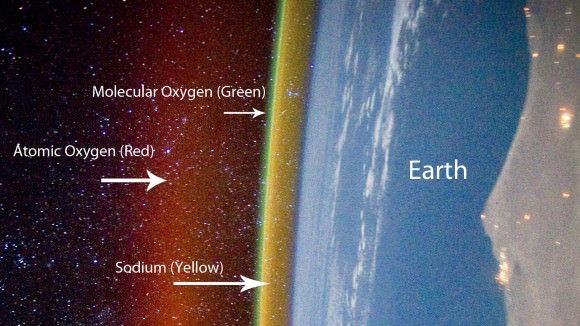

Superheated to millions of degrees by gravitational compression the disk glows brilliantly across the electromagnetic spectrum. Powerful spun-up magnetic fields focus twin beams of light and energetic particles called jets that blast into space perpendicular to the disk.

Blazars and quasars are thought to be one and the same, differing only by the angle at which we see them. Quasars – far more common – are actively- munching supermassive black holes seen from the side, while in blazars – far more rare – we stare directly or nearly so into the jet like looking into the beam of a flashlight.

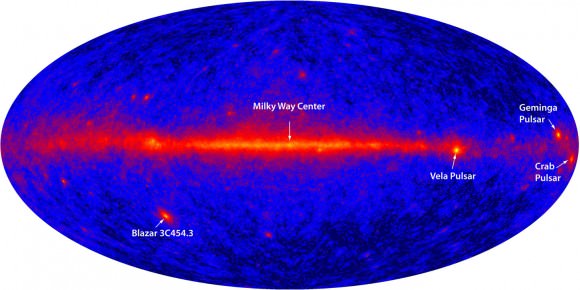

3C 454.3 is one of the top ten brightest gamma ray sources in the sky seen by the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. During its last major flare in 2005, the blazar blazed with the light of 550 billion suns. That’s more stars than the entire Milky Way galaxy! It’s still not known exactly what sets off these periodic outbursts but possible causes include radiation bursts from shocked particles within the jet or precession (twisting) of the jet bringing it close to our line of sight.

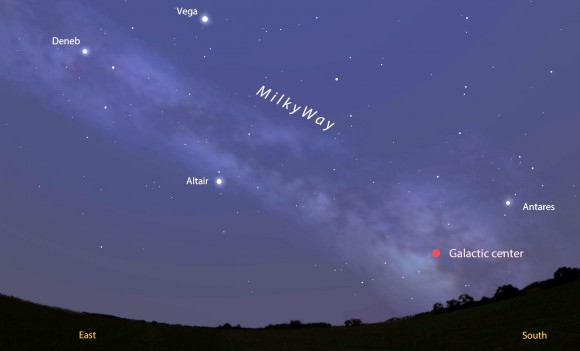

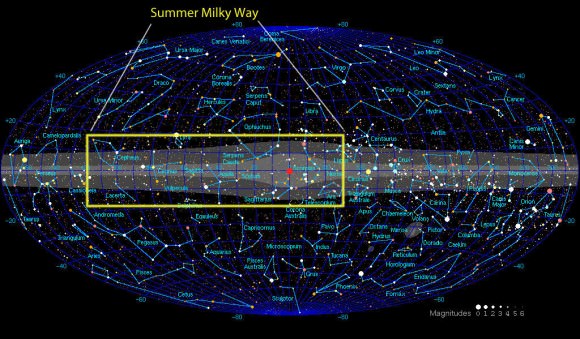

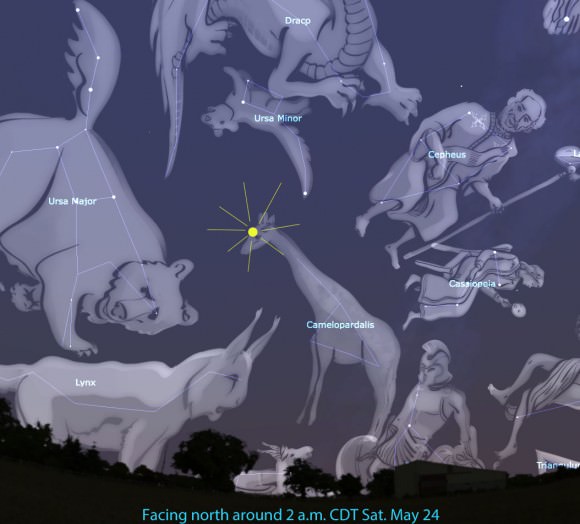

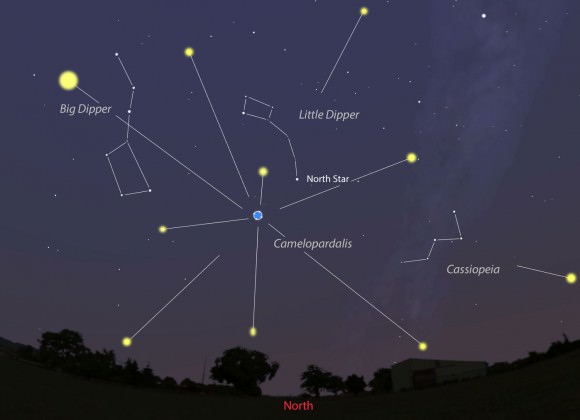

The current outburst began in late May when the Italian Space Agency’s AGILE satellite detected an increase in gamma rays from the blazar. Now it’s bright visually at around magnitude +13.6 and fortunately not difficult to find, located in the constellation Pegasus near the bright star Alpha Pegasi (Markab) in the lower right corner of the Great Square asterism.

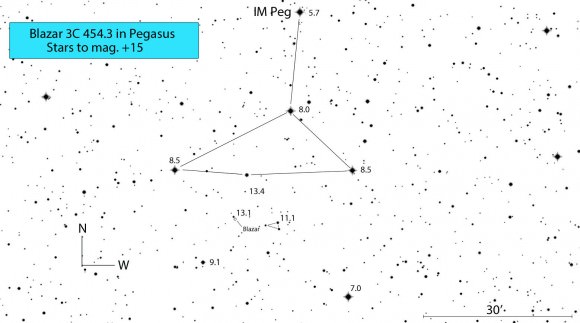

Using the wide view map, find your way to IM Peg via Markab and then make a copy of the detailed map below to use at the telescope to star hop to 3C 454.3. The blazar lies immediately south of a star of similar magnitude. If you see what looks like a ‘double star’ at the location, you’ve nailed it. Incredible isn’t it to look so far into space back to when the universe was just a teenager? Blows my mind every time.

To further explore 3C 454.3 and blazars vs. quasars I encourage you to visit check out Stefan Karge’s excellent Frankfurt Quasar Monitoring site. It’s packed with great information and maps for finding the best and brightest of this rarified group of observing targets. Karge suggests that flickering of the blazar may cause it to appear somewhat brighter or fainter than the current magnitude. You’re watching a violent event subject to rapid and erratic changes. For an in-depth study of 3C 454.3, check out the scientific paper that appeared in the 2010 Astrophysical Journal.

Learn more about quasars and blazers with a bit of great humor

Finally, I came across a wonderful video while doing research for this article I thought you’d enjoy as well.