Tracking down resources on the Moon is a critical process if humanity decides to settle there permanently. However, some of our best resources to do that currently are orbiting satellites who use various wavelengths to scan the Moon and determine what the local environment is made out of. One potential confounding factor in those scans is “space weathering” - i.e. how the lunar surface might change based on bombardment from both the solar wind and micrometeroid impacts. A new paper from a researchers at the Southwest Research Institute adds further context to how to interpret ultra-violet data from one of the most prolific of the resource assessment satellites - the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) - and unfortunately, the conclusion they draw is that, for some resources such as titanium, their presence might be entirely obscured by the presence of “old” regolith.

Ultraviolet (or UV) light has been far less prominent in resource mapping efforts than infrared or visible light. However, it still plays an important role in understanding what researchers are seeing when they look at the soil. In particular, Far Ultraviolet (FUV) on the extreme end of the ultraviolet spectrum, can provide different insights into what the soil is made out of than other spectra, and luckily LRO is equipped with just such a camera.

However, it has been difficult for scientists to interpret data from LRO’s FUV spectra due to notable spectral differences depending on what part of the Moon they were looking at. The SwRI researchers theorized that these differences were caused by the “age” of the regolith - older soil would have been subject to more space weathering. Therefore, the age of the soil might have had an impact on its FUV spectra, which would then have an impact on how scientists should interpret the data from LRO.

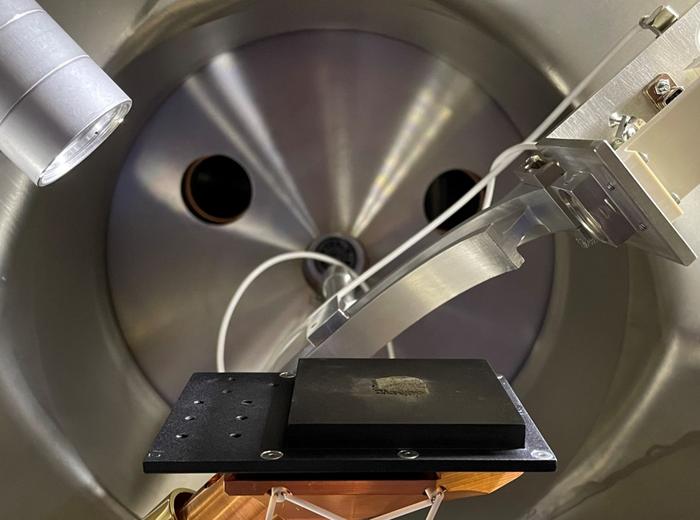

Fraser discusses how to deal with lunar regolith with Dr. Kevin CannonTo test this theory, they gathered samples from three different Apollo soil samples, two of which were “highly weathered” while one, which was collected from inside of a trench, was comparatively young. They then subjected these soil samples to both FUV imaging on Earth as well as scanning / tunnelling electron microscopy to try to determine how their physical features are reflected in their spectra.

They found three key things. First, the older soil samples were covered in nano-size iron particles that were created by the solar wind in what you might call an “iron acne” effect. All of these particles were also very rough from getting hit by meteors over billions of years. The newer soil sample didn’t have nearly as many of these “nanophase” iron particles.

Second, that roughness the iron particle exhibited changed how light reflected off of it. The newer regolith sample, which had lighter grains, exhibited “forward scattering” in FUV, which means the light that hit it bounced away from the light source. Older regolith, on the other hand, with its rough surfaces, backscatters light back towards the light source. Effectively, this made the newer surface appear about twice as bright as the older one in FUV.

Fraser showcases what's so interesting about the lunar south pole.Finally, and perhaps most importantly, they realized that the effects of space weathering were enough to mask chemical signatures about the makeup of the soil itself in FUV. The two “old” Apollo samples they tested were from very different places on the Moon. One was from a mare, which had high titanium content but was dark lava rock. The other was from a highland, with lower titanium content and bright rock. However, under FUV inspection, they looked almost exactly the same, despite being made up of different minerals.

This has implications for the interpretation of data from LRO, as it obfuscates the mineral makeup of many of the soils. Confusingly, the results that paper describes in the lab actually disagrees with physical observations from LRO that show that fresh soil is typically “redder” than older soil, which would imply that its less bright at FUV wavelengths. The authors suggest that discrepancy is due to specific properties of the lunar surface, such as the “fluffiness” of the soil (which was eliminated when the sample was collected) or the presence of “shocked” materials caused by micrometeroids, which were accurately represented in the sample they used.

No matter the explanation, this study contributes to our understanding of what we’re looking at when we look at the Moon in FUV. Accounting for the expected age of the soil is of critical importance for this type of remote sensing, but even in doing so it might be hard to differentiate the type of chemical composition seen on the surface. As we expand our search for lunar resources, it will become increasingly important to collect as much data in as many different wavelengths as we can to understand what we’re working with up there.

Learn More:

SwRI / EurekaAlert - Lunar soil analyses reveal how space weathering shapes the Moon’s ultraviolet reflectance

C.J. Gimar et al - The Influence of Space Weathering on the Far-Ultraviolet Reflectance of Apollo-Era Soils

UT - The Moon's Atmosphere Comes from Space Weathering

UT - One Year of the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter: Top Ten Finds

Universe Today

Universe Today