Many factors influence a planet's habitability. The more obvious ones include being in a star's habitable zone and having a magnetic shield to protect it from radiation. But other important factors are less obvious.

New research points out that for a planet to support life, certain chemical factors have to be in the right balance. In particular, an exoplanet has to have ample phosphorous and nitrogen present in its core when it forms. And for those elements to be available on the planet's eventual surface, oxygen must be available.

The research is published in Nature Astronomy and is titled "The chemical habitability of Earth and rocky planets prescribed by core formation." The lead author is Craig Walton, a postdoc at the Centre for Origin and Prevalence of Life at ETH Zurich.

"A crucial factor governing the habitability of exoplanets is the availability of bioessential elements such as nitrogen (N) and phosphorous (P), which foster prebiotic chemistry and sustain life after its emergence," the authors write. Nitrogen is critical to proteins, which in turn are critical to cells. Phosphorous is a critical part of of both DNA and RNA.

The researchers explain that oxygen availability and oxidation underpin the eventual availability of both N and P. "However, concentrations of P and N in planetary mantles vary, owing to initial availability and oxidation conditions during planet formation, and thus their characterization and availability in planetary environments are challenging."

Walton and his co-researchers turned to modelling to understand the relationship between O, N, and P in a planetary core. They found that much like exoplanets must reside in a "Goldilocks Zone," a distance range from its star that allows liquid water, exoplanets also have a 'Chemical Goldilocks Zone.' "Here we use a core-formation model to show that moderate oxygen fugacity during core formation is the key parameter to the availability of these two elements, with the existence of a narrow ‘chemical Goldilocks zone’ that allows both P and N to be present with the right abundances in the mantle," they write.

Oxygen fugacity is at the heart of this research. Fugacity is like a substance's tendency to escape. Oxygen molecules are always moving around, and at high pressures or low temperatures, molecules behave differently. Fugacity takes these conditions into account and is like an effective pressure, or a molecule's "eagerness" to escape. The research shows that for N and P to be present in the right amounts, the oxygen fugacity has to be just right.

“During the formation of a planet’s core, there needs to be exactly the right amount of oxygen present so that phosphorus and nitrogen can remain on the surface of the planet,” explained lead author Walton in a press release.

"We focus on P and N because these are considered to have been limiting nutrients for life across much of Earth's history, and indeed limiting factors in the prebiotic chemistry that first gave rise to life," the authors write.

Rocky planets like Earth begin as balls of molten rock. In this state, heavier elements sink to the bottom, or core, of the planet. That's why Earth's core is mostly iron, and its mantle and crust largely consists of lighter elements like oxygen and silicon.

That's an overview, but there's lots of detail. Different chemical elements have different affinities for each other, and some lighter elements can be pulled toward the core when attached to heavier elements. Chemical elements that have an affinity for bonding with iron are called siderophile elements. Phosphorous is one of these, and without enough oxygen present, P will attach itself to iron as iron phosphide and sink to the core. Once bound in a planet's core, it is unavailable.

If there's too much oxygen present, it has a different effect. P will remain in the mantle, while N is more likely to escape into the atmosphere and, eventually, into space.

The modelling in the research shows that there's only a very narrow range of oxygen abundance that allows both N and P to remain in a rocky planet's mantle. And, of course, Earth is right in this range.

“Our models clearly show that the Earth is precisely within this range. If we had had just a little more or a little less oxygen during core formation, there would not have been enough phosphorus or nitrogen for the development of life,” said Walton.

The researchers are calling this defining relationship a '*nutrient profile*.' It includes the bulk composition of the solar system it formed in, how the planetary bulk composition is modified compared the system's bulk composition as the planet forms, and how the elements are partitioned between the core, mantle, and crust by oxygen fugacity.

This figure illustrates the nutrient profile and the Goldilocks Zone. Black hatched overlay shows planetary mantles depleted in phosphorous compared to Earth. White hatched overlay shows planetary mantles depleted in nitrogen compared to Earth. Regions with both black and white hatched overlays are depleted in both N and P. Earth sits in the Goldilocks zone. Image Credit: Walton et al. 2026. NatAstr.

This figure illustrates the nutrient profile and the Goldilocks Zone. Black hatched overlay shows planetary mantles depleted in phosphorous compared to Earth. White hatched overlay shows planetary mantles depleted in nitrogen compared to Earth. Regions with both black and white hatched overlays are depleted in both N and P. Earth sits in the Goldilocks zone. Image Credit: Walton et al. 2026. NatAstr.

Earth, obviously, is in the Goldilocks zone. Our sister planet wasn't so fortunate. The modelling shows that on Mars, oxygen was outside of the zone. This sealed Mars' fate, the authors say, and it has more P in its mantle compared to Earth, but less N. That means that in our understanding of what's necessary for life, Mars had no chance.

Unfortunately, we don't have totally accurate measurements of how much P and N are in Mars' mantle. But research has place some constraints on their abundances. Mars rovers have measured P in Martian rocks and found levels similar or slightly lower than Earth's. N concentrations are more uncertain, but scientific estimates show that it's clearly depleted compared to Earth.

While we see surface water as the primary arbiter of habitability, this research shows how much detail is involved in habitability. An exoplanet could sustain liquid surface water for billions of years, which means it's in the putative habitable zone. But it won't necessarily be in the chemical Goldilocks zone.

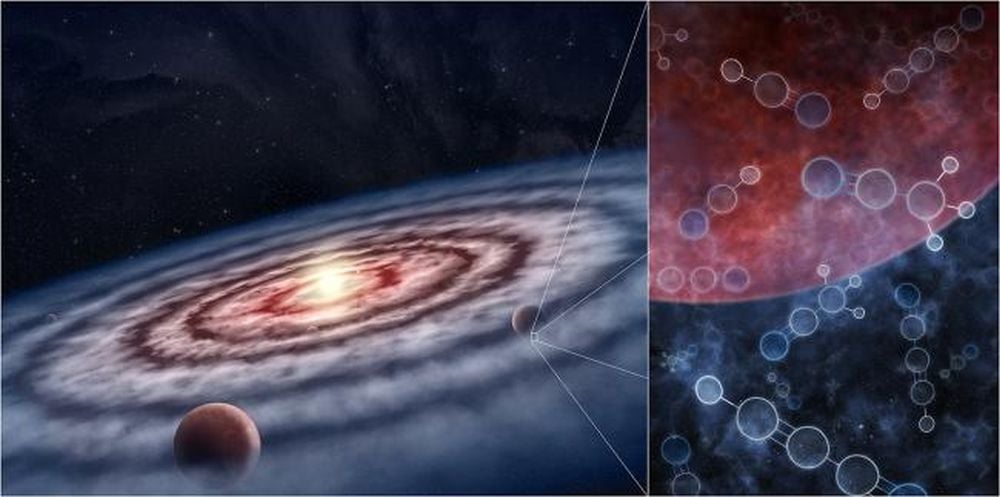

This figure illustrates how the mantle concentrations of nutrients affect the possibility of life on exoplanets. A planet's nutrient profile depends on several factors: the bulk composition it inherits from the solar system, how the planet's bulk composition is altered during formation, and how individual nutrients are partitioned between a planet's core and mantle. Collectively, the study's results show that Earth-like planets are likely rare. Image Credit: Walton et al. 2026. NatAstr.

This figure illustrates how the mantle concentrations of nutrients affect the possibility of life on exoplanets. A planet's nutrient profile depends on several factors: the bulk composition it inherits from the solar system, how the planet's bulk composition is altered during formation, and how individual nutrients are partitioned between a planet's core and mantle. Collectively, the study's results show that Earth-like planets are likely rare. Image Credit: Walton et al. 2026. NatAstr.

When it comes to humanity's ongoing quest to find habitable planets, this research makes an important contribution. To some extent, astronomers can use powerful telescopes to determine the chemical makeup of a planetary system by measuring the chemistry of the star. Planets inherit their chemical compositions from their solar nebulae. If a star has a chemical composition with pronounced differences from the Sun, then its rocky planets are unlikely to exist in the chemical Goldilocks zone.

“This makes searching for life on other planets a lot more specific," said lead author Walton. "We should look for solar systems with stars that resemble our own Sun.”

Beyond examining individual stars in our galaxy, these results could also tell us about the prospects for life across the cosmos. "The chemical habitability zone may be of relevance to understanding the prevalence—or lack thereof—of life in the Universe," the authors write.

We face a growing understanding of the complex web of factors that make Earth habitable, and precious. Contemplating life throughout the cosmos isn't as simple as identifying planets in habitable zones, or planets that have surface water, or planets that have protective magnetic shields, plate tectonics, or even carbon cycles.

"A lack of P and/or N for prebiotic chemistry might create a bottleneck that prevents life from developing on many worlds, even if they are otherwise habitable; for example, species may adapt to and colonize a harsh desert, but they must first arise somewhere more clement," the authors explain.

The idea that life is inevitable elsewhere based purely on the staggering number of planets in the Universe is being chipped away at. Ultimately, we're in no position to make any solid judgements. But this research suggests that planets like Earth, where a million different factors lined up just right, are most likely exceedingly rare.

"Earth appears to represent a planet approximately optimized for coavailability of P and N to life, which would once again render it a relatively rare example of a terrestrial world despite being apparently completely average with respect to its overall oxidation conditions during core formation," the authors write. The search for habitability should be focused on planets that formed in similar conditions to Earth.

"Emphasis should be put on assessing the oxygen fugacity of exoplanets during core formation, which will largely determine the P content of their mantles. This information will be critical for interpreting possible biosignatures associated with distant worlds," the researchers conclude.

Universe Today

Universe Today