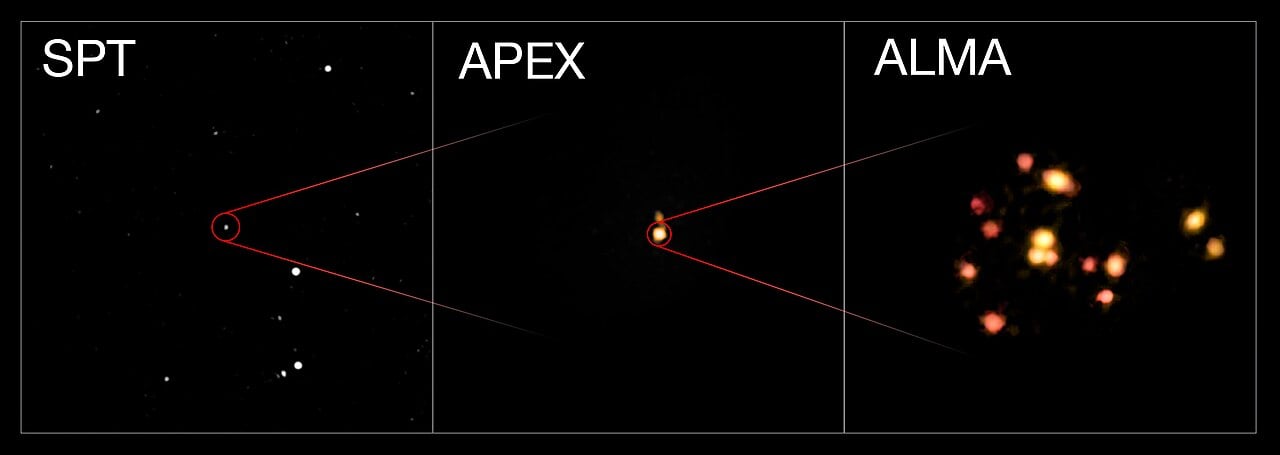

Galaxy clusters aren’t supposed to be scorching hot when they’re young. Like infants, they should need time to mature before developing their full characteristics. Astronomers using the Atacama Large Millimetre/submillimetre Array have just discovered that nature doesn’t always follow the same script.

Looking back nearly 12 billion years, researchers detected superheated gas surrounding the forming cluster SPT2349-56 when the universe was merely 1.4 billion years old. The finding shatters existing models of how galaxy clusters grow up.

The ALMA Radio Array (Credit : ESO)

The ALMA Radio Array (Credit : ESO)

The team used an unusual observation method called the thermal Sunyaev-Zel’dovich effect, which detects hot gas indirectly by observing the tiny shadow it casts against the cosmic microwave background, the faint afterglow from the Big Bang itself. Rather than looking for light emitted by the gas, this technique reveals where energetic electrons scatter photons from that ancient radiation.

“We didn’t expect to see such a hot cluster atmosphere so early in cosmic history,” - lead author Dazhi Zhou, a PhD candidate at the University of British Columbia.

His initial reaction was skepticism. The signal appeared too strong to be real, but months of verification confirmed the remarkable result, that the intracluster gas in this infant cluster burns hotter and more energetically than many present day clusters.

Before this discovery, astronomers assumed early universe clusters remained too immature to fully heat their surrounding gas. No direct detections of hot cluster atmospheres existed from the universe’s first three billion years. SPT2349-56 removes that assumption.

The cluster itself was already famous as one of the most extreme infant systems known. Its compact core, roughly the size of the Milky Way’s halo, hosts more than 30 starburst galaxies building stars thousands of times faster than our Galaxy manages. Several actively growing supermassive black holes lurk within, visible as bright radio sources.

The Antennae Galaxies are an example of a starburst galaxy occurring from the collision of NGC 4038/NGC 4039 (Credit: NASA/ESA)

The Antennae Galaxies are an example of a starburst galaxy occurring from the collision of NGC 4038/NGC 4039 (Credit: NASA/ESA)

Those black holes may explain the unexpected heat. Powerful outbursts from supermassive black holes can inject enormous energy into surrounding gas. According to the new study, these energetic processes could naturally account for overheating the intracluster atmosphere so dramatically and so early.

The measurements reveal a superheated cluster atmosphere at a time when models predicted the gas should remain relatively cool, slowly settling into place. Instead, the birth of massive clusters appears far more violent and efficient at heating gas than simulations assumed.

This discovery pushes the observational record back to the earliest direct detection of hot cluster gas ever reported. It forces scientists to reconsider the sequence and speed of cluster evolution, suggesting that energetic feedback from black holes and intense star formation could transform cool young clusters into hot mature ones far faster than expected.

Source : New Discovery Challenges Evolution of Galaxy Clusters

Universe Today

Universe Today