Galaxies don’t always die dramatically. Sometimes they fade away, slowly strangled by the very black holes at their hearts. Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope and the Atacama Large Millimetre Array have caught one such death in progress, revealing a surprisingly subtle method of galactic murder.

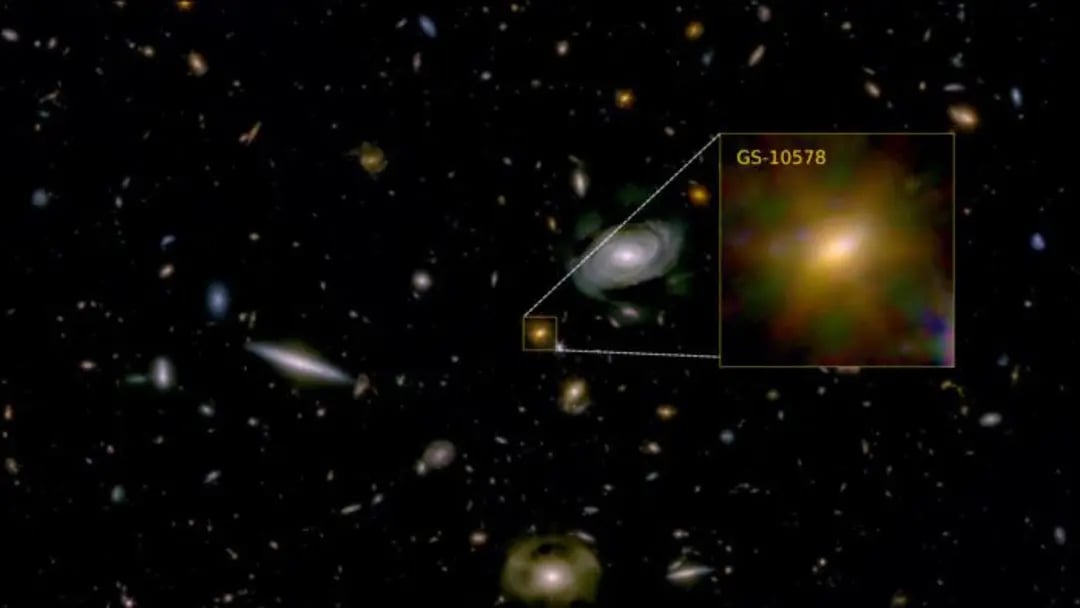

The victim, formally designated GS-10578 but nicknamed ‘Pablo’s Galaxy’ after the astronomer who first studied it in detail, seen as it looked about 3 billion years after the Big Bang. It formed most of its stars between 12.5 and 11.5 billion years ago, accumulating roughly 200 billion times the Sun’s mass in just one billion years. Then, abruptly, it stopped.

Astronomers from the University of Cambridge suspected the galaxy’s supermassive black hole might be responsible, but when they turned ALMA’s radio dishes toward Pablo’s Galaxy for nearly seven hours of observation, they found something unexpected: nothing.

The ALMA radio array (Credit : ESO)

The ALMA radio array (Credit : ESO)

They were searching for carbon monoxide, a reliable tracer of the cold hydrogen gas that stars need to form. The deep ALMA observation should have detected even trace amounts if any remained. Instead, the galaxy appeared almost completely devoid of star forming fuel.

“What surprised us was how much you can learn by not seeing something, the absence of cold gas pointed toward slow starvation rather than a single dramatic event.” Dr Jan Scholtz - Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory.

Meanwhile, JWST spectroscopy revealed powerful winds streaming from the supermassive black hole at 400 kilometres per second, carrying away 60 solar masses of gas every year. At that rate, the galaxy’s remaining fuel would vanish in just 16 to 220 million years, far faster than the billion year timescales typical for similar galaxies.

Yet the galaxy itself looks peaceful. JWST observations show it rotating calmly like a disc, with no signs of the violent mergers that typically disrupt galactic structure. That ruled out external catastrophe as the cause of death.

An image of the core region of Messier 87, a supermassive black hole, processed from an array of radio telescopes known as the EHT with colours indicating brightness temperature (Credit : Event Horizon Telescope)

An image of the core region of Messier 87, a supermassive black hole, processed from an array of radio telescopes known as the EHT with colours indicating brightness temperature (Credit : Event Horizon Telescope)

The answer lies in repeated cycles of heating. Rather than exploding outward in one massive event that tears the galaxy apart, the black hole appears to have heated or expelled incoming gas repeatedly over time. Each episode prevented fresh material from settling into the galaxy’s star forming regions. Cut off from resupply, Pablo’s Galaxy slowly consumed its existing reserves and went dark.

This discovery helps explain a puzzling population of massive, surprisingly old looking galaxies that Webb keeps finding in the early universe. Before Webb’s launch, such objects were virtually unknown. Now they appear more common than expected, and slow starvation by their central black holes may explain how they lived fast and died young, burning through their fuel supplies in cosmic eye-blinks before fading into the darkness.

Sources : Death by a thousand cuts’: Young galaxy ran out of fuel as black hole choked off supplies

Universe Today

Universe Today