The hunt is on for terrestrial exoplanets in habitable zones, and some of the most promising candidates were discovered almost a decade ago about 40 light-years from Earth. The TRAPPIST-1 system contains seven terrestrial planets similar to Earth, and four of them may be in the habitable zone. The star is a dim red dwarf, so the habitable zone is close to the star, and so are the planets. For that reason, astronomers expect them to be tidally-locked to the star.

The JWST was launched to address four main science themes, and one of them is Planetary Systems and the Origins of Life. It can study exoplanet atmospheres using infrared transit spectroscopy, where the light from a star passes through an exoplanet's atmosphere when it transits in front of the star. The JWST can detect molecules in the atmosphere with this method.

The space telescope has done this for multiple targets, including for planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system. But it faces a serious problem: stellar contamination.

New research to be published in The Astronomical Journal outlines JWST observations of TRAPPIST-1 e, a planet about the same size as Earth that's emerged as a prime target in exoplanet science. It's focused on a method to remove stellar contamination in JWST observations of exoplanet atmospheres. The research is "JWST TRAPPIST-1 e/b Program: Motivation and first observations," and it's currently available at arxiv.org. The lead author is Natalie Allen, a PhD student in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Johns Hopkins University.

"One of the forefront goals in the field of exoplanets is the detection of an atmosphere on a temperate terrestrial exoplanet, and among the best suited systems to do so is TRAPPIST-1" the authors write in their research. "However, JWST transit observations of the TRAPPIST-1 planets show significant contamination from stellar surface features that we are unable to confidently model."

In order to know that the JWST is measuring an exoplanet's atmosphere, astronomers need to be able to remove the starlight from the signal. But stars aren't uniform, and doing so is tricky. They have cooler regions called starspots, and hotter regions called faculae. When a planet transits in front of a star, it blocks some of the star, but not all of it. If the planet blocks a starspot or sunspot, it can create false signals that mimic the presence of certain molecules in the planet's atmosphere. Not only that, but a star's limb regions have different temperatures and spectral properties than its center.

This stellar contamination turns the whole endeavour into a complicated puzzle, and it's even worse for a powerful telescope like the JWST because subtle signals can be amplified. "Observations in transmission, however, have been more difficult to interpret," the authors write. "M dwarfs are known to be generally magnetically active, with plenty of evidence of rotational modulation due to stellar surface active regions rotating in and out of view." Not only that, but red dwarfs like TRAPPIST-1 are known to have very active surfaces with lots of flaring, which compounds the problem.

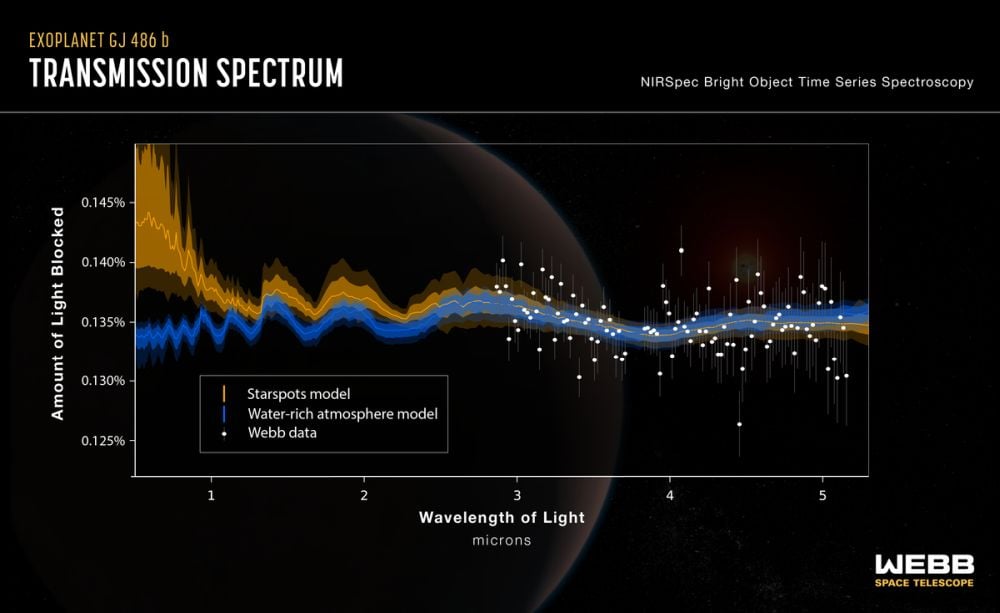

The JWST has performed atmospheric spectrometry on exoplanets before and had to deal with stellar contamination. In 2023 astronomers used it examine the atmosphere of the rocky exoplanet GJ 486 b, a super-Earth that orbits a red dwarf about 26 light-years away. They detected water vapour, an important finding, but weren't sure if the water vapour signal was from the planet's atmosphere or from the star itself.

This image shows the transmission spectrum from the exoplanet GJ 486 b. The JWST detected water vapour but astronomers couldn't be certain the water vapour signal is from the exoplanet's atmosphere or from the starspots on the red dwarf star it orbits. The blue line represents atmospheric signals and the orange ine represents starspots. Image Credit: Illustration: NASA, ESA, CSA, Joseph Olmsted (STScI); Science: Sarah Moran (University of Arizona), Kevin Stevenson (APL), Ryan MacDonald (University of Michigan), Jacob Lustig-Yaeger (APL)

This image shows the transmission spectrum from the exoplanet GJ 486 b. The JWST detected water vapour but astronomers couldn't be certain the water vapour signal is from the exoplanet's atmosphere or from the starspots on the red dwarf star it orbits. The blue line represents atmospheric signals and the orange ine represents starspots. Image Credit: Illustration: NASA, ESA, CSA, Joseph Olmsted (STScI); Science: Sarah Moran (University of Arizona), Kevin Stevenson (APL), Ryan MacDonald (University of Michigan), Jacob Lustig-Yaeger (APL)

Astronomers have already examined another of the TRAPPIST-1 planets—planet b—with the JWST. In fact, the JWST has observed the TRAPPIST-1 system for more than 400 hours, clearly indicating the system's scientific importance. Planet b is airless, so its signals can be used as a baseline to model stellar contamination, and hopefully remove it from the JWST observations of planet e.

"Here, we present the motivation and first observations of our JWST multi-cycle program of TRAPPIST-1 e, which utilize close transits of the airless TRAPPIST-1 b to model-independently correct for stellar contamination, with the goal of determining whether TRAPPIST-1 e has an Earth-like mean molecular weight atmosphere containing CO2," the authors explain.

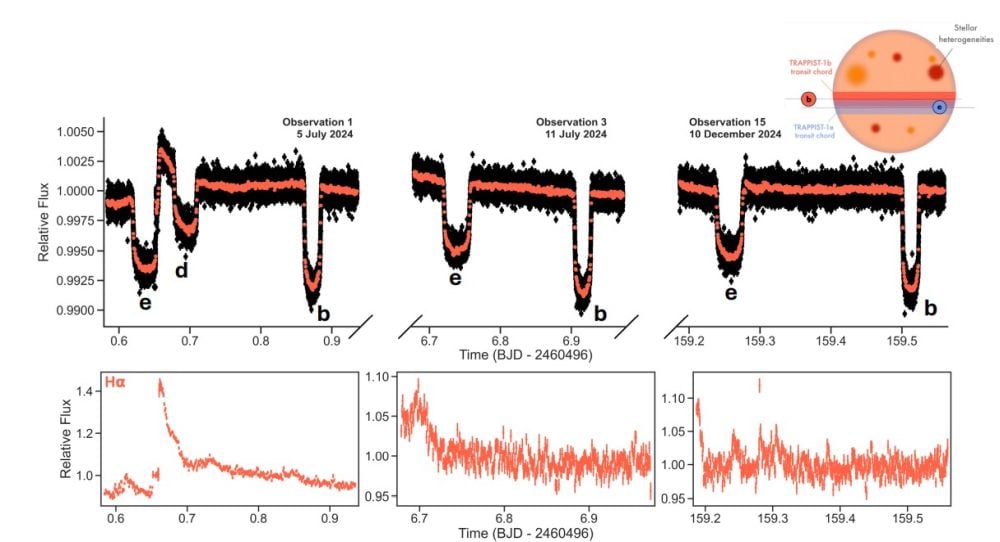

This figure from the research shows some of the results and some of the obstacles that stellar contamination presents. Each panel presents one of the JWST's transit observations, with the panel below showing H-alpha. Peaks in H-alpha represent stellar flaring, and one stellar flare occured right before the egress of planet e. Image Credit: Allen et al. 2025.

This figure from the research shows some of the results and some of the obstacles that stellar contamination presents. Each panel presents one of the JWST's transit observations, with the panel below showing H-alpha. Peaks in H-alpha represent stellar flaring, and one stellar flare occured right before the egress of planet e. Image Credit: Allen et al. 2025.

The paper presents only the first observations of TRAPPIST-1 e in what will be a multi-cycle program. Prior observations of the exoplanet with the JWST revealed extreme stellar contamination. The question they're trying to answer is if their modelling of the airless TRAPPIST-1 b can help them filter out the stellar contamination on TRAPPIST-e. Their results suggest they should be able to, with some caveats.

These first observations highlight the stellar contamination problem.

"The most evident and problematic additional complication in our observations is the presence of flares, visible in every observation in Hα, to differing strengths and frequencies," they write. Starspots and active regions show up prominently in H-alpha observations. All of this activity and observations in H-alpha oppose the idea that TRAPPIST-1 b can be used to understand the atmosphere at TRAPPIST-1 e. "These flares break the inherent assumption of our close transit technique that the stellar surface remains the same between the transits of planet e and b," the authors explain.

But their proposed observation program should be able to get around this. They propose observing only 15 close transits. Close transits are when there is less than eight hours between the transit of TRAPPIST-1 b and TRAPPIST-1 e. That's approximately 10% of the star's 3.3 day rotation period. "This is a small enough fraction of the rotation period that there should not be a significant amount of stellar surface rotation between observations, but is still flexible enough that we are able to find enough close transit instances in the near future," the researchers explain.

The initial results in this study suggest that their close transit method will work.

"We show that we would be able to detect an Earth-like atmosphere with strong significance through our proposed and accepted 15 close transit observations," the authors explain. But it does depend on one specific molecular signal. "Our ability to detect an atmosphere hinges strongly on the presence of the 4.3 µm CO2 feature, predicted as a common outcome of secondary atmosphere formation," they write. Secondary atmospheres are different from a planet's primordial atmosphere because they can reflect biological activity.

The 4.3 µm CO2 feature is significant because that's one of the molecule's strongest absorption bands. Since it's relatively isolated from other signals in a spectra, it's less likely to be confused with stellar contamination.

This study presents a possible solution to the problem of stellar contamination. That problem isn't restricted to TRAPPIST-1, or to only red dwarfs. All stars have surface activity that needs to be accounted for in atmospheric characterization.

"The problem of stellar contamination persists far beyond the TRAPPIST-1 system and has been a significant complicating factor in the search for an atmosphere on a rocky exoplanet, for which we currently have no conclusive evidence," the authors conclude.

Universe Today

Universe Today