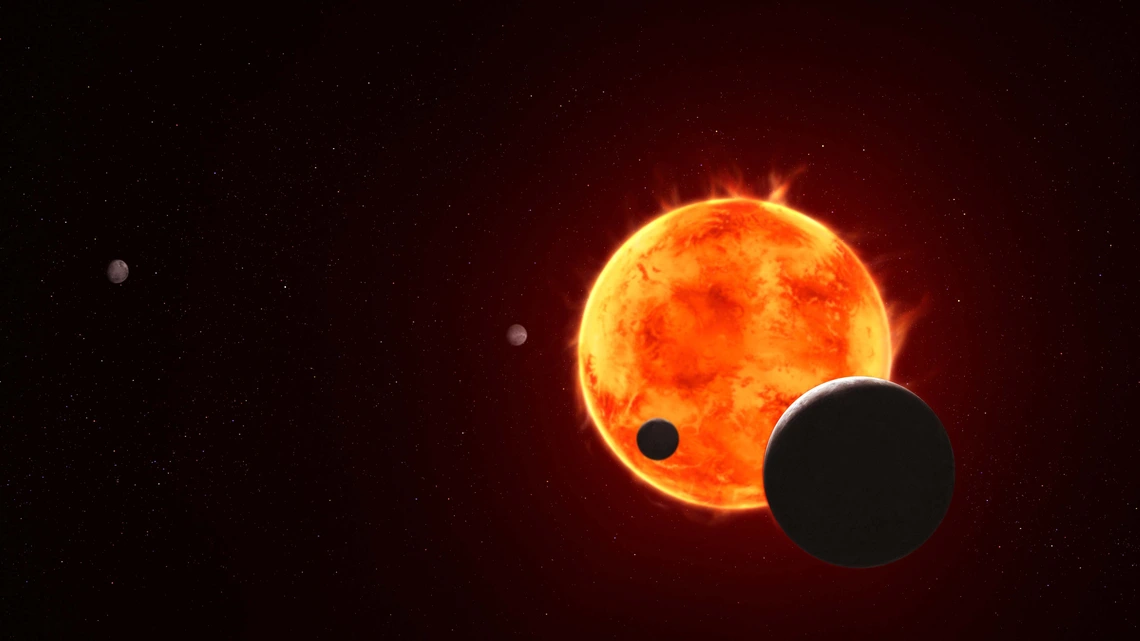

In 2017, astronomers using the TRAnsiting Planets and PlanetesImals Small Telescope (TRAPPIST) in Chile and NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope confirmed the presence of seven rocky planets orbiting TRAPPIST-1, an M-type red dwarf star located about 39 light-years from Earth. What made the system especially intriguing was that three of these planets orbited within (or straddled) the system's habitable zone (HZ): TRAPPIST-1d, e, and f. Since then, scientists have been busy conducting follow-up observations of this system to learn as much as possible about its seven planets and whether they could be habitable.

One planet that has attracted a lot of attention with these observations is TRAPPIST-1e, the only planet that orbits directly within the star's HZ. Thanks to observations made with Spitzer's successor, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), scientists believe they are getting closer to determining whether TRAPPIST-1e can support an atmosphere and maintain liquid water on its surface. In a series of recent papers, the Telescope Scientist Team (TST) shared the results of their initial JWST observations. It proposed several potential scenarios for what the planet's atmosphere and surface could look like.

The observations were made as part of the Deep Reconnaissance of Exoplanet Atmospheres using Multi-instrument Spectroscopy (DREAMS) campaign, which has been using Webb's Near InfraRed Spectrograph (NIRSpec) to spectrally characterize small exoplanets orbiting M-type dwarf stars. When examining TRAPPIST-1e, NIRSpec gathered light from the planet during four transits that took place from mid-to-late 2023. The TST DREAMS team's initial results are detailed in three papers that appeared between September and November in the *Astrophysical Journal Letters*.

Sukrit Ranjan, an assistant professor with the University of Arizona's Lunar and Planetary Laboratory (LPL) and a co-author on the paper, said. "The basic thesis for TRAPPIST-1e is this: If it has an atmosphere, it's habitable. But right now, the first-order question must be, 'Does an atmosphere even exist?'" To this end, the team hopes to capture "transit spectra," where light passes through an atmosphere during a planetary transit. This would not only reveal the presence of an atmosphere but also identify the chemical compounds present (including potential biosignatures such as oxygen, water, carbon dioxide, and methane).

The team observed TRAPPIST-1e during four transits, the results of which are described in their first paper. As they indicated, the spectra they observed hinted at the presence of methane. However, they also acknowledge that the level of stellar contamination was consistent with previous studies of other planets in the system (but over a wider wavelength range). The team was able to marginalize the contamination features, allowing them to rule out the presence of a cloudy, hydrogen-dominated atmosphere.

However, their results hinted at the presence of a secondary atmosphere containing methane, which is the subject of their second paper. To correct for possible stellar contamination, the team conducted simulations of TRAPPIST-1e having a methane-rich atmosphere. The most likely scenario, though it was still very unlikely, was one in which TRAPPIST-1e had an atmosphere similar to Saturn's largest moon, Titan. In this scenario, the planet would essentially be a "warm exo-Titan," Said Ranjan:

While the sun is a bright, yellow dwarf star, TRAPPIST-1 is an ultracool red dwarf, meaning it is significantly smaller, cooler, and dimmer than our Sun. Cool enough, in fact, to allow for gas molecules in its atmosphere. We reported hints of methane, but the question is, 'Is the methane attributable to molecules in the atmosphere of the planet or in the host star?

While the results are ambiguous, they represent a crucial step towards successful exoplanet characterization, one of the JWST's main objectives. Of course, Ranjan and his team express caution in their third paper, emphasizing that the interpretation of their data is theoretical and based on a Bayesian (statistical) analysis. "Based on our most recent work, we suggest that the previously reported tentative hint of an atmosphere is more likely to be 'noise' from the host star," said Ranjan. "However, this does not mean that TRAPPIST-1e does not have an atmosphere – we just need more data."

This research will likely be conducted by next-generation missions, like NASA's Pandora mission - currently in development and slated for launch in early 2026 - and the long-awaited Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO). The former is a small satellite that will monitor stars with potentially habitable planets during transits, and is led by planetary scientists from the University of Arizona's Steward Observatory.

The latter is NASA's next flagship mission, a large infrared/optical/ultraviolet space telescope designed specifically to search for biosignatures on exoplanets. In the meantime, astronomers are hoping that a larger round of ongoing observations and new analytical techniques will further advance exoplanet characterization. The DREAMS collaboration is currently developing a technique called dual transit, which will involve observing the star during simultaneous transits of TRAPPIST-1e and b.

This could allow the JWST to narrow the search for small, rocky planets orbiting red dwarf suns, a job it was not specifically designed for. Nevertheless, the telescope is revolutionizing exoplanet science and delivering the most accurate surveys to date. Said Ranjan:

It was designed long before we knew such worlds existed, and we are fortunate that it can study them at all. There is only a handful of Earth-sized planets in existence for which it could potentially ever measure any kind of detailed atmosphere composition. These observations will allow us to separate what the star is doing from what is going on in the planet's atmosphere – should it have one.

Further Reading: The University of Arizona

Universe Today

Universe Today