(This is Part 3 of a series on primordial black holes. Check out Part 1 and Part 2!)

The early universe was a pretty intense place to be. And not just “early” as in a few billion years ago. I mean early early, just a few seconds after the Big Bang. The universe is small, less than a meter across. It’s hot, with temperatures so high it doesn’t even make sense to say them – they’re just stupidly high numbers with no connection to our everyday existence.

And it was also exotic. The forces of nature were merged together into a single unified whole and were in the process of splitting off from each other as the universe expanded and cooled. Entire epochs would come and go in the blink of an eye, transforming the universe into something totally different, only for it to be transformed yet again.

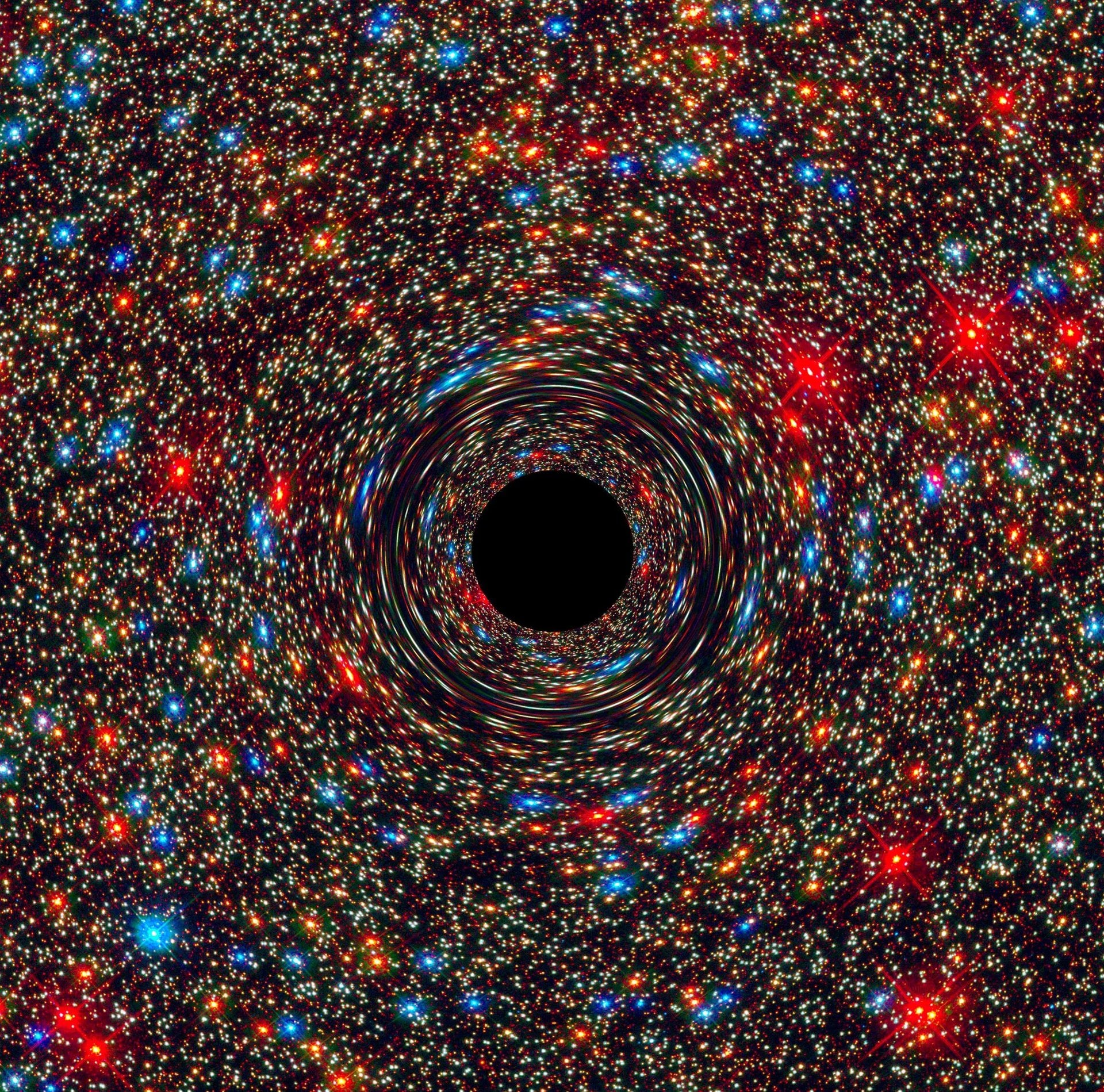

Hawking realized that this chaotic, energized soup might have been the perfect place to breed black holes. Small pockets of matter and/or energy could have been squeezed by who-knows-what to such incredible densities that they just fashioned black holes. No laborious star formation process needed. No limitations based on the total amount of normal matter available. Just pure spacetime and quantum energy conversion into infinitely tiny points.

But how tiny? Well, because this is all a super-hypothetical idea based on not-exactly-well-grounded physics, you could have them as tiny as you want.

And the smaller the black hole, the sooner it evaporates. A black hole made in the early universe – which now get a name name, primordial black holes – with a mass of around 10^15 grams, which is a lot but also not a lot, roughly the mass of a large-ish asteroid or a moon on the smaller side, would take about 10 or so billion years to evaporate.

Hey, last time I checked, which is too frequently, the universe is 10 or so billion years old. Which means if there are primordial black holes with that mass, then they should be evaporating and exploding and doing all sorts of fun energetic things everywhere all the time.

We checked. They’re not. No cosmic explosion fits the profile of an evaporating primordial black hole. Hawking would let the idea slide and move on to other interesting problems.

But like I said, he didn’t set out to solve the dark matter problem. So later when other cosmologists started wanting to really solve the dark matter problem, they rummaged around the attic of discarded physics ideas, and found Hawking’s proposal.

Primordial black holes of mass 10^15 grams and smaller are out – we would’ve seen them by now. But bigger than that? THOSE black holes would still survive to the present day, where they could be roaming the interstellar depths, not interacting or glowing or really doing much of anything. Just sitting there being sources of gravity.

They could be the dark matter.

Now here’s where things get a little interesting. In cosmology, you’re never trying to solve just one problem at once. We have a century’s worth of observations that span all sorts of different eras and epochs and scales in time and space across the universe. We have surveys of millions of galaxy positions. We have detailed images of hundreds of thousands of galaxies. We have the cosmic microwave background. We have big bang nucleosynthesis calculations. We have baryon acoustic oscillations, we have the Lyman-alpha forest, we have…

We have a lot of science.

When you cook up a new proposal, it has to do more than sound cool (and trust me, “dark matter is made of black holes” sounds really, really cool). It has to WORK. You have to do the dirty job and figure out how your new idea fits into all the other cosmological observations that we have access to. If you want to say that the dark matter is made of black holes, then you have to ask how these black holes might affect nucleosynthesis, or the statistics of the cosmic microwave background, or the growth of structure.

AND you have to connect to the wider world of astronomer. If primordial black holes are wandering around, then presumably they are capable of doing SOME interesting things. Maybe they merge together sometimes. Maybe they pass in front of a background star and cause the light from that star to briefly amplify. Maybe they like the clump up in galaxy cores. This is one of the things that separates pseudoscience from real science. Pseudoscience doesn’t take its own ideas seriously, and explore the full ramifications. Real science isn’t afraid to challenge itself and find ways to kill its most promising ideas.

Anyway, when we put primordial black holes through the ringer, and look at them through every possible lens available, we find that they are not a viable candidate for dark matter. Maybe. Kind of. I mean, it’s complicated.

To be continued...

Universe Today

Universe Today