The JWST was built with the power to observe the red-shifted light from objects in the very early Universe. Once it got going, the telescope practically inundated us with surprising, theory-challenging observations from the Universe's earliest ages. Some ancient galaxies were much larger and fully-formed than thought. So were their supermassive black holes (SMBH).

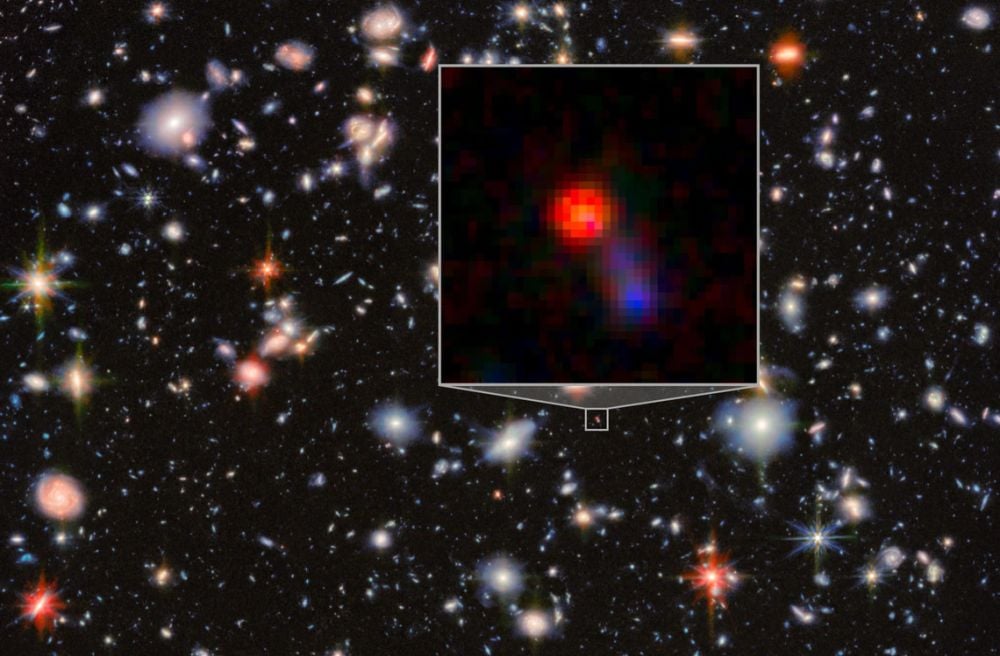

Now, astronomers working with the Webb have found another puzzling early galaxy from when the Universe was only 800 million years old. It's a classic Jekyll and Hyde situation. When viewed in optical and ultraviolet light, it looks pretty much the same as most other galaxies. But when the JWST observed it in infrared, it appears as a raging, gluttonous beast.

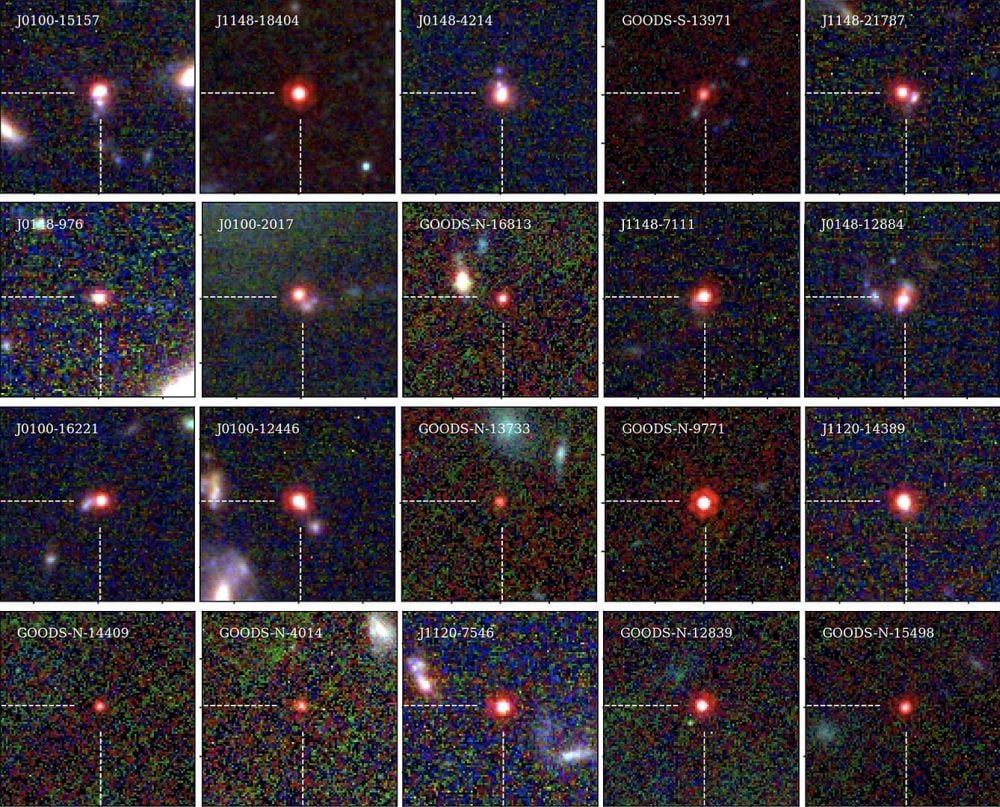

The galaxy is called Virgil, and it's one of the Little Red Dots, a class of object discovered by the JWST. The telescope has found more than 300 of them. They existed between about 600 million and 1.6 billion years after the Big Bang, with most concentrated in the earlier part of that range. They're at the limits of the JWST's range and are very challenging to observe. Virgil is the reddest of the LRDs discovered so far.

Astrophysicists want to know what happened to the LRDs. They were apparently abundant in the early Universe, especially around 600 million light-years after the Big Bang, but then mostly disappeared by about 1.6 billion years after the Big Bang. There are different theories about what happened to them. The leading theory involves the evolution of the Universe and the dark matter in it. As the Universe evolved, dark matter haloes became large and gained increased angular momentum, making it harder for LRDs to form. They most likely evolved into the galaxies we see around us today.

The new observations of Virgil are in research published in The Astrophysical Journal titled "Deciphering the Nature of Virgil: An Obscured Active Galactic Nucleus Lurking within an Apparently Normal Lyα Emitter during Cosmic Reionization." The lead author is Pierluigi Rinaldi, now from the Space Telescope Science Institute, but formerly with the Steward Observatory at the University of Arizona.

"Since its launch, JWST has pushed the boundaries of the redshift frontier, with groundbreaking discoveries at very high redshift," the authors write. The authors point to the discovery of Extremely Red Objects (ERO), of which LRDs are a particular type. "The study of these sources and their nature has triggered a huge amount of literature in a very short time," the authors explain.

*These are 20 of the Little Red Dot galaxies discovered with the JWST. Their discovery was first announced in March 2024. Image Credit: Jorryt Matthee et al 2024 ApJ 963 129DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ad2345URL: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-4357/ad2345, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=154052277*

*These are 20 of the Little Red Dot galaxies discovered with the JWST. Their discovery was first announced in March 2024. Image Credit: Jorryt Matthee et al 2024 ApJ 963 129DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ad2345URL: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-4357/ad2345, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=154052277*

"JWST has shown that our ideas about how supermassive black holes formed were pretty much completely wrong," said co-author George Rieke, a Regents Professor of astronomy and a pioneer of infrared astronomy. "It looks like the black holes actually get ahead of the galaxies in a lot of cases. That's the most exciting thing about what we're finding," Rieke said in a press release.

The JWST's Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam) or Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) can only observe in optical wavelengths this early in the Universe's history. Those observations show that it's a relatively normal galaxy, forming stars at an average rate, and hosting an appropriately-sized black hole in its center. But the JWST's MIRI, or Mid-Infrared Instrument, can see infrared light from this epoch. The MIRI observations pierced the dust surrounding Virgil and revealed its true nature. It hosts a supermassive black hole that's deeply obscured by dust and that is emitting enormous amounts of energy as it feeds.

When SMBH are actively accreting matter, they're called active galactic nuclei (AGN). When AGN attract matter, it gathers in a rotating accretion ring. The gas and dust in the ring heat up, releasing high-enery light. Light from distant, ancient AGN like Virgil is extremely red-shifted and detectable by the JWST.

"Virgil has two personalities," said Rieke. "The UV and optical show its 'good' side – a typical young galaxy quietly forming stars. But when MIRI data are added, Virgil transforms into the host of a heavily obscured supermassive black hole pouring out immense quantities of energy."

"MIRI basically lets us observe beyond what UV and optical wavelengths allow us to detect," said lead author Rinaldi, whose doctoral research was focused on MIRI observations. "It's easy to observe stars because they light up and catch our attention. But there's something more than just stars, something that only MIRI can unveil."

MIRI requires more time to take deep images than the JWST's other instruments. That means that many of the JWST's surveys are done with NIRCam and NIRSpec, which require less time. As a result, there could be many more objects like Virgil out there, highly obscured by dust, whose true nature can only be revealed by longer exposures with MIRI. There could be a significant population of these types of LRDs that scientists are unaware of. If there are, they may have played a larger role than thought in the evolution of the cosmos. They could be linked to the cosmic dawn, when the Universe was reionized only about 200 million years after the Big Bang.

But the researchers point out how complex the object is and how difficult it is to determine its true nature. "By comparing the UV- and Hα-based SFRs, we find that Virgil may be transitioning into—or fading out of—a bursty phase," they write. This indicates a "... limited role in Cosmic Reionization," explain, even though "Overall, Virgil’s spectral properties align with the average galaxy population during the EoR."

The researchers aren't certain that what they're seeing is an AGN. Some diagnostics show that it's an AGN typical of those at high redshifts, "but when accounting for redshift evolution, its classification becomes ambiguous," they write. It can be difficult to disentangle light from star formation from that of an AGN.

But in the end of their analysis, they settle on the AGN explanation. "While modeling this source remains challenging, our results show that the fits consistently require the presence of a dust-obscured AGN, consistent with the findings of E. Iani et al. (2025)," they explain.

In any case, the authors write that Virgil is one of the most extreme LRDs found so far.

The fact that no other LRDs like Virgil have been discovered is probably because of observational bias, according to the researchers. "Are we simply blind to its siblings because equally deep MIRI data have not yet been obtained over larger regions of the sky?" Rinaldi asked.

The researchers intend to find out by performing more long-exposure observations with the JWST's MIRI. If they find more of them, a narrative will develop that puts LRDs into the context of the evolution of the Universe.

"JWST will have a fascinating tale to tell as it slowly strips away the disguises into a common narrative," said Rinaldi.

Universe Today

Universe Today