With new technologies comes new discoveries. Or so Spider Man’s Uncle Ben might have said if he was an astronomer. Or a scientist more generally - but in astronomy that saying is more true than many other disciplines, as many discoveries are entirely dependent on the technology - the telescope, imager, or processing algorithm - used to collect data on them. A new piece of technology, the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, is exciting scientists enough that they are even starting to predict what kind of discoveries it might make. One such type of discovery, described in a pre-print paper on arXiv by Vito Saggese of the Italian National Institute for Astrophysics and his co-authors on the Roman Galactic Exoplanet Survey Project Infrastructure Team, is the discovery of many more multiplantery exoplanet systems an astronomical phenomena Roman is well placed to detect - microlensing.

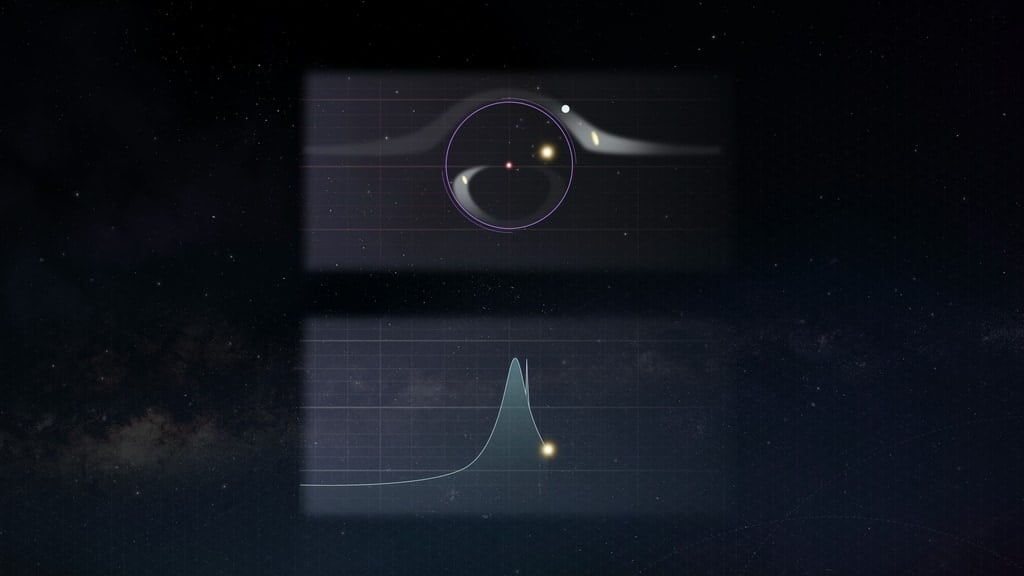

We’ve reported on microlensing here at UT - and we’ve also highlighted some of the most astonishingly beautiful images it can produce. But as a refresher on how it works - if a star in a background passes directly behind a star in the foreground, the massive gravity of the closer star will bend the light, according to the Theory of General Relativity, to greatly magnify the star, and in this case the planets, that are farther away.

Roman is designed specifically to capture those gravitational lenses and use them to analyze details that would otherwise be invisible due to how far the source systems are. Of particular interest in this paper is the telescope’s ability to detect multiple planets from a single microlensing event. This has been done before using other telescopes, but only a handful of times - or technically 11 times, which is by definition more than a handful. Since these events are so rare, the working on exoplanet detection for Roman were curious about how capable the telescope would be.

Fraser talks about Nancy Grace Roman's Coronagraph as a critical tool in its planet-hunting efforts.Detecting multiple planets in a system using this technique is difficult to say the least. To check just how difficult, the authors ran an experiment by creating 1.3 million synthetic light curve datasets that were designed to simulate “triple-lens” systems, which are made up of one star and two planets.

The detection infrastructure wasn’t perfect, but it did correctly identify 66.3% of all triple-lens systems as just that. But there are some factors that majorly impact its ability to detect both planets as well as the star.

First is the location of the planet compared to its star. The paper breaks these distances down into three categories - close, wide, and “resonant”. Resonant, which is defined as when the planets themselves are located near the Einstein Ring, is the best case scenario. Detection levels jump to 93% when this is the case. The worst case scenario is when both planets are “wide” - essentially far away from their star. In this case the detection threshold drops to only 55% - still good but still below average for the system as a whole. Close planets that orbit near their star are somewhere in the middle in terms of detection efficiency.

Fraser discusses gravitational lensing - the phenomena Roman will rely on to find these triple-lens systems.Planetary mass is the second consideration. If both planets are massive (Jupiter size or larger), the likelihood of detection jumps to 90%, whereas if they are both on the smaller side, they often get lost in the “noise” the synthetic light curves intentionally had added to them to mimic real-life conditions. Mixed systems, with one massive and one small planet, had mixed results. If the massive planet is too much bigger than its companion, its gravitational pull can overshadow the signal from the smaller planet.

These two factors have dynamic interactions, but with 1.3 million dataset there are plenty of examples of each style of system. But ultimately, what does this simulation mean for Roman’s expected data output? The authors calculate that, over the mission’s operational lifetime, its expected to capture 64 triple-lens events, making up about 4.5% of all of the exoplanetary microlensing events Roman is expected to find.

When comparing that to how many we’ve found, it will increase the total number of these observable systems by a factor of six. Sure some of them will have some new insights about planetary formation or orbital mechanics. But if nothing else, it will offer a good showcase of what new technology can do.

Learn More:

V. Saggese et al - Predictions of the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope Galactic Exoplanet Survey. V. Detection Rates of Multiplanetary Systems in High Magnification Microlensing Events

UT - Roman Telescope Could Turn up Over 100,000 Planets Through Microlensing

UT - The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope Will Teach Us A Lot More About Cosmic Voids

UT - Roman Space Telescope Will Be Hunting For Primordial Black Holes

Universe Today

Universe Today